Farmers’ march …. Aasim Sajjad Akhtar

IT has been 20 years since the iconic peasant movement on the Okara military farms reached its zenith. Having been intimately involved with the struggle of tenant-farmers to secure their historic claims to 17,000 acres of prime agricultural land in the heart of Punjab, I can testify to the conscious effort made by the movement to remind society that peasants remain a political force in the 21st century, whilst also challenging taboos about the military’s corporate interests.

Today, farmers are once again on the roads. Under the aegis of the Kissan Ittehad, thousands of landowning farmers are protesting the inexplicable decision to import millions of tonnes of wheat in the face of a bumper harvest at home. The refusal of the government to purchase home-grown produce at a reasonable price has resulted in a glut and major losses for many wheat farmers.

While centred in Punjab, the Kissan Ittehad mobilisation is far more geographically diverse than the peasant movement of two decades ago, which was based largely in Okara and revolved around the fate of tenant-farmers on state-owned land. It is also notable that the Okara protagonists were landless peasants demanding proprietary rights, whereas the present movement features owner-proprietors that are contesting agrarian policies.

This not the first time that relatively prosperous middling farmers have taken to the roads. The Kissan Ittehad has been mobilising for some years now, taking up issues such as electricity costs (tube well use), seed, fertiliser and pesticide prices, as well as the erosion of agricultural support measures like guaranteed prices for staple crops.

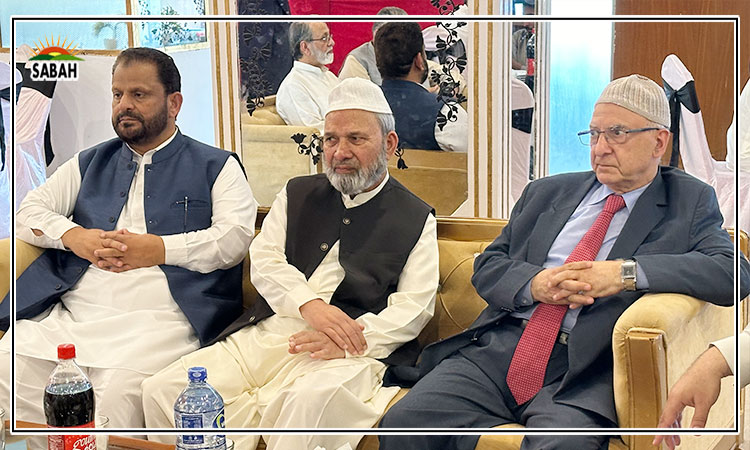

Even the more comfortable farming segments are protesting.

The poorest peasants — landless or owning a modicum of land — are, of course, also impacted by agrarian market logics, but the fact that even more comfortable farming segments are protesting underlines the changing contours of peasant politics.

While the struggles of small and middling farmers is in part due to the profiteering of middlemen — known as arthis and beoparis — agribusiness firms have come to play a dominant role in Pakistan’s agrarian markets. These are companies — domestic and multinational — that try and exercise monopoly control in the supply (including patenting) of inputs and machinery, transportation and storage of produce, and the circulation of commodities.

Agribusiness garners astonishing annual government subsidies in North America and Western Europe. Its takeover of agriculture in countries like Pakistan has been less conspicuous, in part because, as is the case with the manufacturing sector, at least some multinationals subcontract to local firms.

Meanwhile the state has completely reneged on support for peasant farmers, particularly smallholders. Autonomous government entities like the National Fertiliser Corporation and Punjab Seed Corporation have become largely toothless in the face of big private companies, as well as the policy dictates of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank and other donors that sing the praises of the ‘free market’ by eliminating support prices and facilitating agribusiness.

Of course, state functionaries engage in brazen pursuit of profit of their own accord when they feel like it. The current wheat import scandal is a classic example, dictated by the (caretaker) federal government despite some opposition by the provinces. Former caretaker prime minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar claimed that the decision was good for consumers, conveniently neglecting mention of the private sector businessmen who were given licences to bring in the imported stocks and earn windfall profits.

The rhetoric also confirms that government officials clearly prioritise urban ‘consumers’ over peasant-farmers. A meaningful policy matrix would not be based on such a zero sum game between rural and urban; it is possible to ensure both that peasant-farmers are supported and urban consumers also catered to.

Last but not least, big landowners and rich farmers are not on the roads, in part because they operate like capitalist businessmen. They earn money through a host of diversified assets and then declare it as agricultural income, which is not taxed. That needs to change, as does the lack of regulation of agribusiness and middlemen.

More generally, the state must acknowledge its responsibilities towards small and landless farmers. Land reform, if undertaken in both agricultural and peri-urban areas where agriculture is being swallowed up by real estate mafias, could change the fate of almost 30 million peasants who are now landless, as well as pastoralists who have been almost completely invisibilised as common lands are grabbed by state and capital alike.

Those who decide our fate will never take such steps on their own, so farmers will have to keep marching to force their hand.

The writer teaches at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.

Courtesy Dawn, May 10th, 2024