Winter protest…Sajjad Ahmad

IT is neither Gilgit nor Skardu this year. While annual winter protests, sit-ins, marches and fiery speeches have sadly become a hallmark of Gilgit and Skardu divisions, this time it is Chilas in Diamer that has been embroiled in a weeks-long sit-in. The focus this year is the Diamer-Bhasha dam under construction in Gilgit-Baltistan.

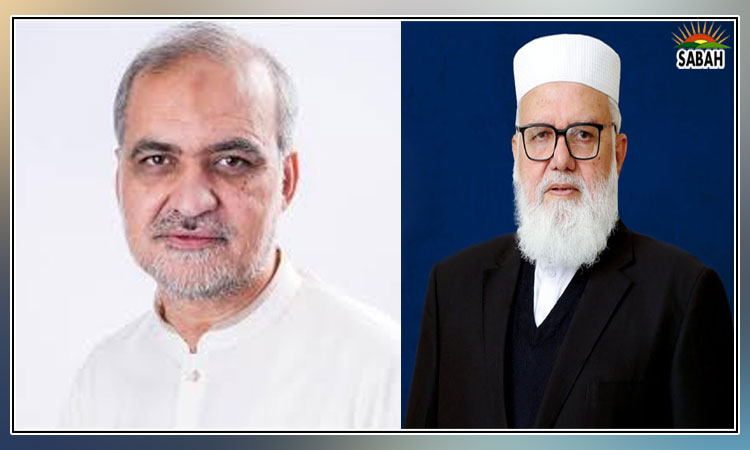

On Feb 16, the Huqooq Do, Dam Banao (Give Rights, Build Dam) movement, led by Maulana Hazratullah, was launched in Chilas. On March 5, some enraged protesters stormed the offices of Wapda, which is working on the dams construction, and locked the premises. The protest was not unexpected; the situation had been evolving for quite a while. Just a few days before the sit-in, Diamer Youth Movement leader Shabbir Ahmad Qureshi blamed the Wapda chairman and the GB chief secretary for their lack of interest in resolving the residents grievances and for the delay in providing relief to the affected people of Diamer.

For a decade now, GB has been in the spotlight for one thing or another. Be it wheat subsidy, taxation, land reforms, or demands for self-governance, the peoples complaints have triggered some powerful protests in the region, which have tended to continue for weeks. Successive federal governments have failed to resolve the chronic issues of GB and have relied on ad hoc solutions. Resultantly, one after the other, the protests and marches bring together large crowds, and civil and political leaders come up with a demand list.

The current episode is a repeat telecast. Locals protest due to what they perceive to be unfair treatment at the hands of the centre; they give a list of their demands; the government forms a powerful committee, mostly after the prime minister has taken note (the PM only take notice after several weeks of protests); the recommendations given are often not sincerely or fully implemented, leaving room for future protests. And the cycle goes on.

For a decade, GB has been in the spotlight for one thing or another.

The ongoing movement has also issued a 31-point charter of demand. The key demands include the immediate implementation of agreements signed with Wapda in 2010 and 2021, land compensation as per current market values determined by the GB government, essential services and healthcare support for all affectees, allocation of six-kanal (3,035 square metres) of agricultural land for each affectee, as promised under the 2010 agreement, and inclusion of locals in the household resettlement package (Chulha Package). The movement has widespread support from GBs CSOs, traders, lawyers, political, religious and nationalist parties and their leaders who are calling for immediate government intervention.

This movement is important and different from previous ones. For the first time here, a mega infrastructure project of the Pakistan government has become the focus of protests. It is not because the locals are against the dam itself but because they havent been compensated as per the agreement with Wapda. The state is determined to construct this reservoir to meet Pakistans water shortages, as reflected in an earlier energetic campaign, led by a Supreme Court chief justice, to collect funds for the dam a few years back. Fundraising dinners were organised, many public and private organisations deducted one or two days salary of their employees. As if this were not enough, schools were asked to organise bake sales and parents had to buy overpriced cupcakes to fund the dam.

However, when it comes to compensating communities displaced by the dam building, there is less enthusiasm and delays ensue. Wapda officials have acknowledged these delays and resettlement issues.

Another criticism of the locals is that they are not fairly treated in construction work. They say that the dam workers are mostly brought in from down country, while local labourers have been ignored. Furthermore, with the prolonged sit-in and intensification of the protests, they have refused to talk to the GB government. Perhaps they are aware where the real decision-making power lies with the centre and its bureaucracy. That is why the chief secretary of GB is often blamed in such demonstrations.

The question to address is: why do these issues come to the fore and trigger protests in GB every year? Is it because the centre is not willing to delegate decision-making powers to locally elected assembly members? If the state considers GB a part of the Kashmir issue then why are there two different set-ups in the two regions?

One of the long-standing demands of GB is to give the region a Kashmir-type set-up. Although the extent of autonomy for the latter is often debated, this could be a start towards transferring powers to the local authority and to abide by the UN resolutions on Kashmir.

The writer is assistant professor and fellow of the Centre for Business and Economic Research at IBA, Karachi.

Courtesy Dawn