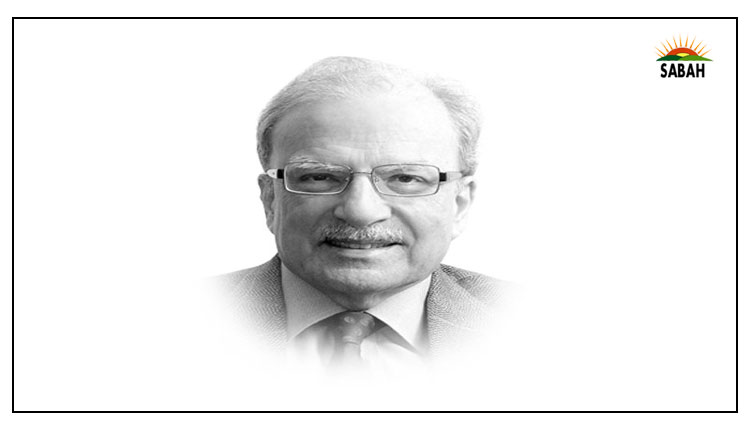

Why America loses wars ….. Shahid Javed Burki

Given the number of wars the United States has fought and mostly lost in the period since its victory in the Second World War, it has become a favoured piece of analyses to study the various aspects of these conflicts. These analyses are undertaken by social scientists as well as by newspapers.

“Do we still understand how wars are won?” was the headline of an article written by Bret Stephens for his newspaper, The New York Times. America withdrew in humiliation from Saigon in 1975, Beirut in 1984, Mogadishu in 1993 and Kabul in 2021. Washington withdrew from Baghdad after the tenuous victory of the troop surge in 2011 but returned three years later after the Islamic extremist group, the ISIS, swept through northern Iraq. The ISIS advance was stopped with the help of Iraqis and Kurds.

The Americans won limited victories against Iraqi military dictator Saddam Hussein in 1991 and Liberian dictator Muammar el-Qaddafi in 2011. Both were killed but it is recognised by the scholars who have studied these operations that the endgames were fumbled. Stephens in the above-referred article makes some interesting observations. “If you’re on the left, you’d probably say that most if not all of these wars were unnecessary, unwinnable, or unworthy. If you’re on the right, you might say that they were badly fought — with inadequate force, too many restrictions on the way force could be used or an over-eagerness to withdraw before we had finished the job… Either way, none of these wars were about our very existence. Life in America would not have changed if, say, Kosovo was still a part of Serbia.”

The focus of this article is the important question: Why does America continue to lose despite its incredible military strength? Scholars and policymakers in Pakistan should follow the conduct of America’s little wars across the globe. I once contacted Imran Khan before he became prime minister. This was done at the urging of the then Afghan President Ashraf Ghani who had twice invited the Pakistani leader to visit him in Kabul. Ghani was puzzled by his absence of response. I met Imran at his residence in Bani Gala who had a reason for his absence of response to Ghani. “He is a close ally of the Americans while I have problems with the way Washington has carried out campaigns in our tribal areas. Using drones, they have destroyed houses while the men who lived in them were fighting in the hills. Thousands of women and children were killed,” he said.

Even after the Americans had pulled out their troops, impressive amount of investigative reporting has been done by the press in the United States on how their country acted in Afghanistan in its two decades long operations. Several aspects of this engagement have been studied including the role played by one individual, an Afghan fighter named Abdul Raziq.

On May 23, The New York Times wrote a long story on what it called “America’s monster”. The subject of the story was the anti-Taliban fighter named Abdul Raziq, who, according to the newspaper’s report, was “one of the most important partners in the war against the Taliban”. He appeared before a crowd along with two prisoners; made them kneel and while they were pleading for mercy, they were executed by Raziq’s men. In the silence that followed the execution, Raziq addressed the gathering who had come to watch. “You will learn to respect me and reject the Taliban,” he said after the killing which took place in the winter of 2010. For years, American military leaders lionised Raziq as a model partner in Afghanistan, their ally in the battle against the Taliban. “If only everyone fought like Raziq, we might actually win this war, American commanders often said,” wrote Azam Ahmed and Mathieu Akins in their story for The Times.

His effectiveness as an American ally was built on years of torture, extrajudicial killings and the largest-known campaign of forced disappearances during America’s 20-year war in Afghanistan. The newspaper studied America’s 20-year involvement in Afghanistan by investigating thousands of cases that left a poor legacy for America in this critical country. The culture of lawlessness and impunity Raziq created “flew in the face of endless promises by American presidents, generals and ambassadors to uphold human rights and build a better Afghanistan,” commented the newspaper as a conclusion of its extensive work.

Raziq “ruled over the crucial battle ground of Kandahar during a period when the United States had more troops on the ground than in any other chapter of the war, ultimately rising to the rank of lieutenant general thanks to the backing of the United States. American generals cycling through Afghanistan made regular pilgrimages to visit him, praising his courage, his ferocious war fighting and the loyalty he commanded from his men, who were trained, armed, and paid by the United States and its allies,” wrote Ahmed and Akins.

Raziq went on to orchestrate the brutal campaign of enforced disappearances in Afghanistan. Most of those who disappeared were killed and buried in unmarked graves. He not only targeted the Taliban; he also focused on the rival tribal clan, the Noorzai. Raziq was an Achakzai. While the Americans were close to him, using all kinds of laudatory phrases to describe the man and the role he had played in helping them fight their war, he left a legacy that has greatly damaged his country.

A 2013 United Nations report noted a surge in unidentified bodies, some still handcuffed, dumped in mass graves in Kandahar City and dozens of reported disappearances, citing the “increased level of brutality and torture under Raziq”. For countless Afghans, he was a monster who needed to be punished for the cruelty he had exhibited towards his countrymen. This was done. He was walking next to General Austin S Miller, the top American commander at that time in Afghanistan, when he was gunned down by an undercover Taliban assassin in 2018. His killing was celebrated not only by the Talban but also by ordinary citizens of the country.

Raziq’s legacy is the dysfunctional government that took control of Kabul after the Americans pulled out on August 15, 2021. The American decision to pull out and the clumsy way in which it was executed is also the subject of study. I will turn to that story later. These developments across the border have had tremendous consequences for Pakistan. One outcome is the revival of extremist terror in the country’s northern districts.

Courtesy The Express Tribune, June 3rd, 2024.