Who cares about education? … Arshad Saeed Khan

“All are equal, but some are more equal than others” – this is a simplified version of the quote from George Orwell’s book ‘Animal Farm’, which can be applied to the set of selected human rights advocated by civil society and the media in Pakistan.

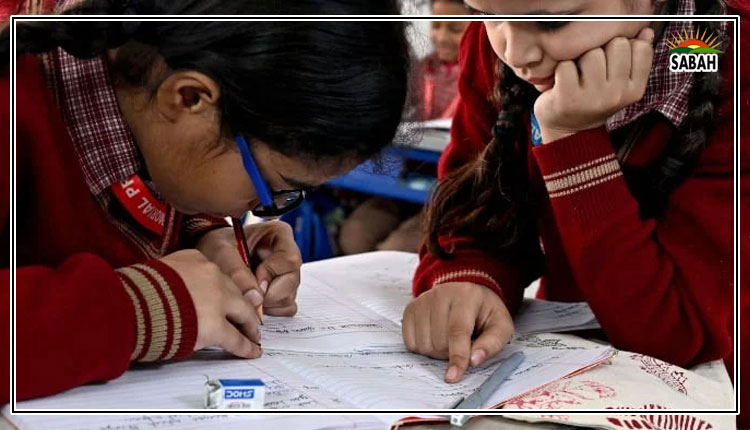

Although the UN stresses the indivisibility and equal importance of all human rights, in Pakistan some rights garner far more attention from civil society and the media while others, such as the right to education, are shamefully neglected. Politicians campaign relentlessly for civilian supremacy, journalists fight for freedom of expression, and gender activists push for women’s empowerment, but who will champion the cause of the 25 million children deprived of their fundamental right to education?

Media outlets dedicate countless hours to talk shows on political and economic issues, and public service messages on climate change and sanitation. Yet, the education crisis affecting millions of children barely makes it to the screen. Can a nation ever hope to progress without educating its children and youth?

In 1948, the UN declared free and compulsory education a fundamental human right through Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It took Pakistan 62 years to incorporate this right into its constitution with the enactment of Article 25-A in 2010, guaranteeing free and compulsory education as a fundamental right of all children and placing the responsibility of its provision on the ‘state’. However, 13 years since its passage, this legislation remains largely ineffective due to government inaction.

Over 25 million children aged five to sixteen years are still out of school; including 20 million who had never stepped inside a classroom, a failure that should be a national scandal but instead remains under the radar. Is this not a grave violation of the constitution of Pakistan? Why have human rights organisations and the NA Standing Committee on Human Rights not convened any meeting to review the status of implementation of the constitutional right to education?

This neglect stems from a deeply rooted social disconnect. The urban elite, whose children are educated in high-quality private institutions, rarely engage with the crisis in the public education system. They dominate the national discourse on human rights but seldom champion the right to education for the marginalised millions. Their silence is mirrored by successive governments, both federal and provincial, that prioritise infrastructure projects and short-term political gains over long-term investments in education.

The apathy of the state to the constitutional right to education of all children is evident from a few alarming facts. Education funding has been consistently slashed. Pakistan’s spending on education has dropped from 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2015-16 to a shocking 1.5 per cent in 2023. This drastic underfunding reflects not only a lack of political will but a blatant disregard for the future of the country.

At a time when Pakistan needs to invest in its human capital, the state has chosen to abandon its children, particularly in the most vulnerable districts of Sindh, Balochistan, southern Punjab, and the merged districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where over 50 per cent of children remain out of school.

As a whole, 58 per cent in Balochistan and 46 per cent of children aged five to 16 years in Sindh are out of school. Over 60 per cent of girls are out of school in 57 districts of the country, reveals an analysis of 2023 Population Census data. Do these alarming statistics ring any bells in the ears and minds of people at the helm of affairs in Pakistan?

In Punjab, the country’s most populous province, the education crisis is glaring. Despite being home to 31.5 million illiterates and over nine million out-of-school children, Punjab allocates just 13 per cent of its annual government budget to education, the lowest among all provinces.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, by contrast, allocates 25 per cent of its budget to education. Yet instead of addressing this crisis, the Punjab government has pursued a policy of ‘rationalising’ schools, merging or closing them down in the name of efficiency. Between 2001 and 2023, over 10,000 public schools were shut down in Punjab, even as the province’s population surged from 72.5 million in the 1998 Census to 127.6 million in the 2023 Census.

This reduction in the number of schools has been accompanied by a sharp decline in the number of teachers also. In 2018, there were 391,799 teachers in public schools across Punjab. By 2023, that number had fallen to 333,039, a reduction of nearly 60,000 teachers in just five years. As a result, the student-teacher ratio has risen, further diminishing the quality of education in an already crumbling system. Despite these alarming figures, there has been no meaningful explanation from the Punjab School Education Department, leaving many to question whether the state’s priorities lie elsewhere.

The UNDP’s Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024 reveals that 93 million people in Pakistan are living in poverty. The report places Pakistan in the group of five countries with the largest number of people living in poverty, which accounts for nearly half (48.1 per cent) of the 1.1 billion poor in the world. In the case of Pakistan, the contribution of ‘education deprivation’ to its overall Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is the highest (41.3 per cent), compared to the other four countries.

The link between poverty and education is undeniable. Studies have repeatedly shown that most illiterate and out-of-school children come from poor families, trapped in a vicious cycle of deprivation that only education can break. Yet, despite overwhelming evidence that free and compulsory education is the key to lifting people out of poverty, the federal and provincial governments in Pakistan continue to divert resources away from public-sector education.

Investment in infrastructure projects, designed to win votes, takes precedence over the long-term benefits of educating the next generation. This blatant misallocation of resources reflects not just poor governance but a shocking disregard for the basic rights of Pakistan’s children.

The constitution of Pakistan, alongside international human rights declarations, guarantees every child the right to free education. But the government’s inaction tells a different story; one of neglect, indifference, and broken promises. It is time for civil society, media, and public representatives in Pakistan to wake up to this crisis and demand the enforcement of Article 25A – the right to free and compulsory education for all children – in letter and spirit, in all areas, irrespective of gender, caste, and creed.