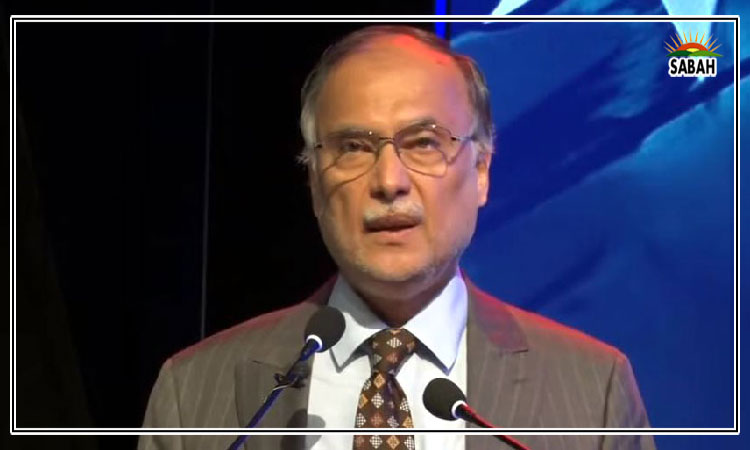

Throwing the VPN baby out……Abbas Nasir

THOSE who govern us may have expertise in multiple areas, but their ability and propensity to score own goals seem without parallel. None of us will have to look too hard to find examples. The latest of these are curbs on the internet.

Pakistan often competes with India because it sees its eastern neighbour as a fierce rival and often gives the impression it has the desire and the ability to match it in all spheres. But does any Pakistani who believes this ever reflect with honesty on whether it is true?

India is about four times bigger than Pakistan in terms of land mass and five to six times larger in population. Now, if we were competing like for like, we’d have been justifiably smug if, for example, our trade volume, foreign exchange reserves, GDP and other key development indicators reflected this proportion.

Who doesn’t know the history which tells us that while our eastern neighbour had political (leadership) continuity well past its first decade as an independent state (16 years to be precise), saw meaningful land reforms and investment in education, with at least five world class IITs (Indian Institutes of Technology) set up within the first 14 years of its existence. Not forgetting the passage of its first constitution in 1950.

In our case, a similar period of our existence saw the father of the nation passing away within 13 months of independence, assassination of his political heir apparent a few years later, and then a devastating and debilitating game of thrones which witnessed politicians and civil-military bureaucrats passing through a revolving door in power grabs, sanctioned by a superior judiciary that sullied itself and set the theme for years to come.

While India stayed on the democratic course, Pakistan strayed and strayed and strayed from it, in a tradition that continues to this day. The one area where Pakistan appeared to be ahead was in economic growth and development, funded by throwing in its lot with the West (read: the US) during the Cold War years and beyond.

In different forms, this slight edge continued till the early 1990s, when Manmohan Singh became India’s finance minister and embarked on an unprecedented reform and deregulation plan, which was to transform India’s economy and fate within a few years. There has been no looking back for it since.

Of course, critics of any such analysis would ask if Indian society is any better than Pakistan’s as a result of this economic growth and development. They’d cite the rise of Hindutva ideology and list its negative impact on the country and its unity. That would be valid criticism, as that is true.

Any such analysis does not for a moment suggest that Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was wrong in seeking and securing a separate homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent. He was right. It was his tragic death soon after independence that pushed Pakistan off track and into the direction in which it finds itself today.

The religious intolerance and strife in society and the extra-constitutional role and transgressions of various power players in the country since Mr Jinnah’s passing would have enraged him no end, and, frankly, they would not have happened had he lived through the initial years of Pakistan. But he did not.

What we have as a result is an unmitigated mess where various hugely power-hungry and self-righteous players and their petty agendas take precedence over what is vital for the collective good of the country and its citizens.

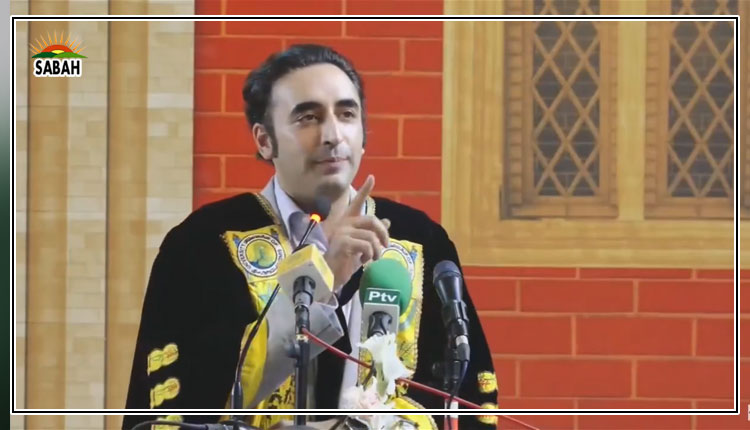

While many executives of Indian origin are now at the helm of global technology giants (a tribute to the quality education imparted by the IITs, 23 of which exist today with an enrolment of nearly 100,000 students at any given time), we are still debating whether free access to the internet is highly desirable or anathema to our society.

I became aware through an anecdote of the quality of IIT education when, in the early 1990s, my nephew, then at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), told me that he was quite surprised to see some Indian students transferring directly from IITs to MIT undergrad programmes.

The result of this education and Dr Singh’s reform was that the Indian tech sector grew exponentially, like the rest of the economy. India today is home to some of the world’s leading technology companies, and their software exports total more than $200 billion a year, and are likely to grow further. India’s exports are services-led. So should ours.

Pakistan’s software exports are around $3.2bn annually. By no means is this comparison meant to run down our companies and IT professionals but merely to demonstrate the growth potential. Our firms have performed so well even when unsupported by government policy — not just unsupported, but often restricted, as is happening with this new VPN allergy that the rulers have developed.

Whatever the rationale they have cited for restricting free access to the modern tools of communication and information technology, it will not stand the test of time nor sanity. Contentious political issues will not be resolved by turning off the IT tap.

In fact, it is tantamount to turning off the water, food supply (even oxygen) to an entire city’s population because hiding among them are some terrorists. Any law enforcement has to be targeted and pinpointed. This collective punishment is self-defeating.

Instead of scoring own goals, those running the country should reflect and ask themselves whether they wish to see Pakistan as a modern developing/ developed state with its abundant youth talent contributing to its development, earning it billions in badly needed foreign exchange, or a dysfunctional isolationist security state perpetually in need of bailouts with all their negative consequences.

Courtesy ![]()