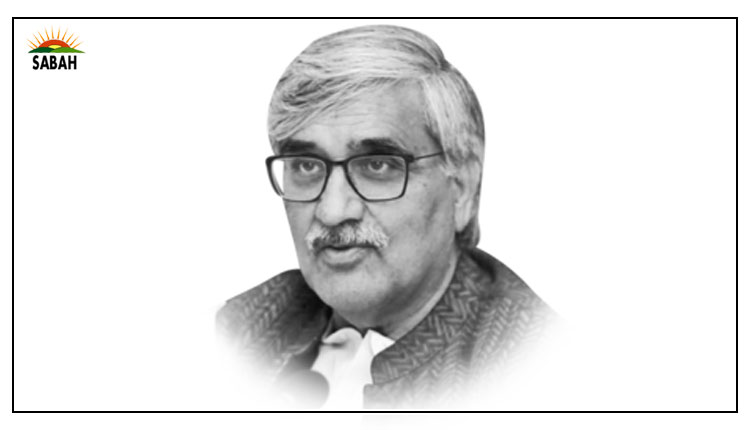

The making of manifestos ۔۔۔۔Ahmed Bilal Mehboob

THIS is the season when political parties generally produce their election manifestos. Over the past many elections, this has been more a ritual than a substantive exercise, because political parties feel that a large segment of voters don’t bother much about reading election manifestos to make up their minds about voting or not voting for a party. They may have been right until a few elections ago when a growing middle class, the rise of social media and the youth bulge in the voters’ list started changing poll dynamics. At least an emerging class of voters is no longer content with the traditional politics of slogans, tall promises, opponent-bashing and communicating with voters on issues only during elections. Voters demand greater engagement. Sadly, more than half of registered voters choose not to vote as indicated by the average 45 per cent voter turnout of the past eight elections, partly because of traditional politics.

Potentially, over 21 million new voters will be voting in the coming general election. Their knowledge about political parties and what these parties stand for is limited to mostly half-cooked information on social media. Smartly crafted and effectively communicated election manifestos may bridge the gap between political parties and voters, especially the young voters who number around 57m, or more than 45pc of the total registered voters. Election manifestos, therefore, need more serious attention from political parties. Here are six key ideas to make the election manifesto a substantive document:

Bottom-up consultative process: Hardly any political party in Pakistan involves its grassroots organisations and workers in identifying key policy issues, which need to be addressed, in their election manifestos. In contrast, the Conservative and Labour parties in Britain have established systems of holding policy forums at various levels, starting from the constituencies up to the national forum, and finally seeking endorsements at annual party meetings. The Conservative Policy Forum website indicates that at least half the election manifesto consists of recommendations made by policy forums at various levels. In Pakistan, political parties, with very few exceptions, constitute a committee consisting of 20 to 50 persons about two to three months before polling day. The three largest political parties — the PTI, PML-N, and PPP — unveiled their election manifestos just 16, 20, and 27 days before the 2018 election was held. The process indicates that the election manifesto is considered a mere formality rather than the result of a properly structured system of consultations at various levels. In principle, holding at least district-level discussions will not only mobilise the party cadre, it will also give them stakes in party policy formulation. A number of fresh ideas may also crop up during these consultations. Since there is very little time left for holding grassroots consultations for the 2024 election, at least provincial consultations should be arranged by each party, giving representation to each district.

Informed manifestos: The process of making election manifestos is usually based on whim and not proper research. Although there is an increasing tendency in political parties to commission public opinion surveys, the general focus is on gauging the popularity of various leaders rather than the identification of issues. The use of public opinion polls based on a carefully crafted questionnaire can significantly enhance the ability to identify key issues and, therefore, the quality of manifestos.

Well-crafted election manifestos can bridge the gap between political parties and voters.

Manifesto, not a mere wish list: Almost all election manifestos in Pakistan are mere wish lists, without any serious back-end working on how the resources will be mobilised or diverted from other programmes to implement the manifesto. For a resource-constrained country like Pakistan, trade-offs are a natural phenomenon while undertaking serious planning on policies and programmes. Election manifestos should, therefore, present the party’s proposed trade-offs and funding ideas. Labour’s election manifestos of 2017 and 2019 may serve as good models as these carried separate documents explaining how promised programmes would be funded. The Labour manifestos in 2017 and 2019 carried seven- and 40-page appendices titled ‘Funding Britain’s future’ and ‘Funding the real change’ respectively. Both these funding documents were produced by a team headed by the shadow chancellor of the exchequer — a shadow minister of finance in our parlance had we had a system of shadow cabinets in our polity.

Provincial manifestos: Pakistan is a federal state and a lot of ministries and divisions have been devolved to the provinces. A party might not be in power both at the centre and in all the four provinces at the same time. The parties should prepare separate manifestos for the federation and each province. The Jamaat-i-Islami recently unveiled a separate election manifesto specifically for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Other parties may consider doing the same.

Monitoring progress of manifestos: Parties should also focus on devising a system to monitor the progress on the implementation of the manifesto’s aims if and when they come to power, and describe such a system in the manifesto. There would be greater voter trust in a party which includes self-appraisal in its manifesto. The PML-N manifesto of 2013 had included a brief chapter on the implementation of the manifesto but was hardly practised. The PTI, after assuming control in 2018, tried to monitor the implementation of Imran Khan’s first 100 days’ agenda and shared the results online, but the party abandoned the commendable initiative even before the expiry of its first 100 days in government.

Checklist of key issues: The manifesto should identify key issues of a short-, medium- and long-term nature and propose possible ways to address them. In the present context, besides combating terrorism, the economy should be the top priority focusing on energy-sector reforms, enhancing exports and investment, and privatising state-owned enterprises. Improving human development, ushering in justice system reforms, maintaining effective local governments, conducting political dialogue for harmony and improving relations with neighbouring countries as well as civil-military ties should be the mid- to long-term focus.

The writer is president of the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency.

president@pildat.org

X: @ABMPildat

YouTube: @abmpildat

Courtesy Dawn, November 12th, 2023