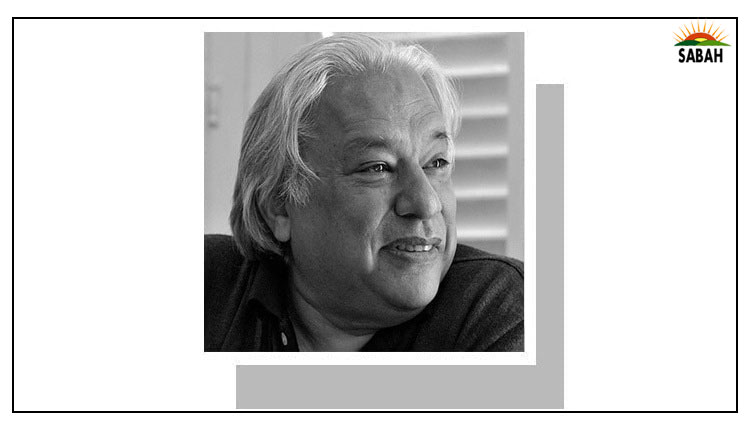

The disappeared … Arif Hasan

IT is normal in Pakistan to die because of some accident. This happens all the time and in fairly large numbers. Most of these deaths are avoidable.

You can be walking along a road which has a high compound wall running along it. Without any notice, it can collapse, injuring you, and if you have a child walking with you, it is possible that he may die. Then, while you are sitting and having tea, the building in which you are sitting can also collapse. If you are shopping, the mall can catch fire, and so can high-rise buildings, and more often than not, the fire engine hose cannot reach the storey where the fire is most intense. It is also important to note that factory fires have killed hundreds of Pakistani workers.

Traveling in Pakistan has also become very dangerous. If you are catching a PIA plane, it is more than possible that it will not take off for reasons that are not explained to the travellers. If you take a train, it might be derailed, catch fire, or one of your fellow passengers might even be raped by the railway caretakers. Then, if you are travelling by road, your vehicle might fall into a ditch or be submerged by a landslide.

It is also possible that you may be robbed at gunpoint and even shot if you have the wrong name. If, on the other hand, you are travelling by boat, it is possible that the boat will sink, and if you are fighting a legal battle on a land issue, the witness in your favour can be shot dead, and that too within court premises, and the case in point can continue for over 20 years.

Pakistanis tolerate all this, as no political party considers these issues important enough to be taken up in their party manifestos or election campaigns. This is because the politicians belong to the elite of the country, and these are not issues they are affected by. However, it has to be pointed out that they control the institutions of the state that are responsible for the accidents identified above. These accidents are seldom deliberate and are not part of government policies.

Another reason is that in Pakistan, if you are rich and privileged enough, you can buy the type of justice that suits you, through bribery and nepotism. This kills all transparency, makes accountability almost impossible, and puts the blame on the working class in the administrative system or on the junior middle-level bureaucracy and technical staff.

However, there is a crime that routinely takes place which is far more serious than all the deaths listed above put together: and that is the crime of forced disappearance of persons who are picked up from their homes and are taken away without their relatives knowing why they are being taken away, where are they being taken to, for how long, and what they have been accused of. There is sufficient evidence to show that this is being done by state agencies as part of their policy.

A very large number of those who have been kidnapped and/or disappeared belong to Balochistan, and some of them have later been found dead in deserted places. Their relatives have been waiting for their return, in some cases, for more than 20 years. One can only imagine the pain this has caused to their relatives and the shame to the more conscientious of Pakistanis.

The Baloch have fought for their rights since the inception of Pakistan, and during Gen Ayub and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s time, their struggles (which were armed ones) were led by their sardars and for which they took to the hills to challenge the state. These struggles were terminated through negotiations.

However, things have changed; the new Baloch generation is urban and well-educated. They represent the future, and sardars do not represent them. Like all young people emerging out of oppression, they are radical, hungry for knowledge, and anxious for a change from the stifling status quo in which they have been forced to live, and in keeping with the emerging trends in Pakistan. Their women are playing an increasing role in political and social movements.

If the state does not recognise and cater to these changes, especially in a region where there has been an unaddressed history of conflict with it, it is more than possible that an East Pakistan-like situation can emerge.

The government in power needs to release all disappeared persons, make available the bodies of those who have been killed so that funeral rituals can be performed, and set up the necessary institutional arrangements that ensure that in the future there will be no disappearances that lack a registered FIR and/ or in violation of human rights as enshrined in the Constitution of Pakistan.

Courtesy DAWN