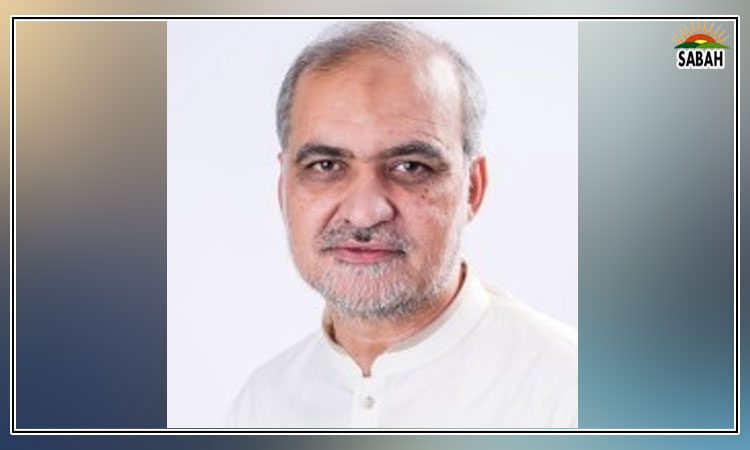

Storytelling as therapy…Ghazi Salahuddin

If you are unnerved by the national state of affairs and unable to figure out what the rulers and leaders of this country are doing, there is one place you can retreat into and be at peace with yourself, if only for a brief period.

But what is that place I am alluding to and would it require some kind of a physical movement? Well, I was thinking of the possibility of escaping into the magical world of a dastan or the realm of fantasy that is enclosed in a story or a book of fiction. That listening to a story or reading a novel can be a therapeutic exercise is what I am trying to say.

The screenshot shows Shahnaz and Fakir Aijazuddin speaking to the audience. Facebook/mohattapalacemuseum

The screenshot shows Shahnaz and Fakir Aijazuddin speaking to the audience. Facebook/mohattapalacemuseum

I would not be surprised if you, my readers, are a bit mystified by this statement. Actually, I am using a peg to move on to my favourite theme of how literature, specifically fiction, can benefit a society like ours. The obvious inference, then, is that our abysmally low reading habits may have contributed to the rise in intolerance and extremism and the spread of violence across various sections of our society.

First, let me refer to the encounter that I am using as a peg for this column. I had the good fortune of attending an event at the Mohatta Palace Museum in Karachi on Friday, one segment in the distinguished lecture series meant to commemorate 25 years of the museum.

The rather extended title of this lecture was: The art of the Hamzanama painting, literature and dastangoi in Mughal Lahore. It was a fascinating excursion into the magical realms of not just Hamzanama but mainly Tilism-e-Hoshruba, evoking the medieval tradition of storytelling.

It featured Shahnaz and Fakir S Aijazuddin, a power couple that shines on our cultural and literary firmament. Fakir Aijazuddin dealt with Hamzanama as an art historian and Shahnaz Aijazuddin delved into the wonders of Tilism-e-Hoshruba, the Urdu magical epic that she had condensed into a one-volume English translation that was published in 2009. The two dastango, Nazr-ul-Hasan and Syed Meesam Naqvi, presented a highly dramatic rendition of a dastan. And there were two giant, 250-year old naqqaras brought from Sehwan that were played to conclude an evenings escape into the world of magic.

This is not a report of the event that was a rare treat for its select audience. Hameed Haroon, with his poetic eloquence, set the stage for an enchanting evening. But I need to quickly hop over to the importance of storytelling and of fantasy in making the lives of the people more meaningful and more endurable.

We, for instance, know that Einstein would advise parents to read fairy tales to their children to make them more intelligent. The idea, simply, was to enlarge the boundaries of a childs imagination. It was in this context that Einstein believed imagination to be more important than knowledge.

Incidentally, Shahnaz Aijazuddin mentioned Harry Potter and the magical realm created by J K Rowling as an extension of a dastan like Tilism-e-Hoshruba. There was some reference, also, to Tolkiens high fantasy novel Lord of the Rings. I see this as the continuation of the old tradition of storytelling.

It has been suggested that these fantasy novels as well as science fiction have contributed to the creativity and inventive thinking of young people, particularly in the United States. Some years ago, The Guardian had a weekly column titled Book Clinic in which experts replied to readers questions as to what books they should read to deal with specific personal problems or social issues.

I recall one reader posing this question: Which books will restore my faith in politicians? I wonder if there are any relevant books for a Pakistani critic to suggest while answering a similar question from a regular viewer of talk shows. However, the quality of our politics would certainly not be what it is if most of our politicians were readers of books.

There was this German novel by Nina George, The little Paris bookshop, about a middle-aged man who operates a bookstore on a barge on Seine in Paris as some kind of a literary apothecary. He has the gift of sensing which books will soothe the troubled souls of his customers. His purpose is to use literature to help people improve their lives.

We have the word: bibliotherapy. It is a therapeutic approach employing books and other forms of literature, typically alongside more traditional therapy modalities, to support a patients mental health. It involves storytelling or the reading of specific texts.

Psychologists have said that fairytales teach children how to deal with basic human conflicts, desires and relationships in a healthy way. But storybooks are not within the reach of all our children. For that matter, so many of them are out of school and are stunted for lack of nourishment. And that tradition of grandmothers telling bedtime stories has almost ended, also because the grandmothers and their grandchildren often do not speak the same language.

I do realize that these thoughts would appear to be haphazard and somewhat incoherent. Perhaps I am not able to fully elucidate the need that we have for the magic that is enshrined in, say, Tilism-e-Hoshruba and Alif Laila and fairytales to be able to deal with the abrasive realities of our life.

One motivation for me was an article I read this week in The New York Times by a Brazilian journalist with this title: Telling stories to my daughter got me through the darkest times. When Bolsonaro won Brazils presidential election in 2018, Vanessa Barbara was nursing a four-month old daughter. On one of those lonely nights, she started to tell random stories to her daughter, just to feel less alone and to divert her sad feelings.

She wrote: Little did I know that this, the simple act of telling tales, would see us through an unhinged far-right presidency and a devastating pandemic. In the toughest of times, it was a lifeline.

Courtesy The News