Security decisions …. Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry

NEARLY every country facing the kind of security challenges that Pakistan confronts maintains a national security council (NSC) as a principal decision-making body that brings together the civil and military leadership onto one platform. However, in Pakistan, this idea has not been fully embraced.

Gen Ayub Khan constituted a national advisory council to give the impression of collective decision-making by the civil and military leadership. In 1969, Gen Yahya Khan established an NSC for advice. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto constituted a cabinet committee on national security in 1976. Gen Zia also created an NSC in 1985 but abolished it the same year. In 1997, the interim government of Malik Meraj Khalid established a council for defence and national security to aid the government but the idea was abandoned by the elected dispensation, which preferred the forum of a defence committee of the cabinet.

In October 1998, Gen Jehangir Karamat floated the idea of an NSC for institutionalised decision-making on national security. However, the suggestion was resisted by the Sharif government on grounds that it would give constitutional legitimacy to the army’s role in political governance. Gen Musharraf revived the idea in 2004 and set up an NSC as a statutory body, which worked till 2008. In 2013, prime minister Nawaz Sharif softened up to the idea but reconstituted it as a national security committee (not council), subservient to the cabinet.

Evidently, the idea of having an NSC could never take root in Pakistan. The story is no different when it comes to the office of national security adviser. Pakistan had NSAs in 1969, 2004 to 2008, and then 2013 to 2022. Since April 2022, there has been no NSA.

There is no consensus in Pakistan about the role of an NSC.

Clearly, there is no consensus in Pakistan about the powers and role of an NSC. Civilian rulers perceive it as a forum to give the military a greater say in political governance, which, they believe, undermines the mandate of elected governments.

A counter argument is given that since an NSC is chaired by the prime minister and includes several leading cabinet members, involving the military leadership in decision-making on critical issues of national security could strengthen, rather than weaken, the hands of the civilian government. Further, given our ground realities, a high-level civil-military forum for collective decision-making could address misunderstandings before these morph into military interventions.

Given the enormous geostrategic changes underway globally and regionally, and instability on our borders with Iran, Afghanistan and India, Pakistan needs an NSC to address security challenges. It is worth noting that national security is now defined more comprehensively as a tripod of traditional security, economic security and human security. Given the interconnected and wider spectrum of threats to national security — external, internal and non-traditional — a whole-of-the-nation approach is needed.

It would also be relevant to look at how the rest of the world is managing decision-making on issues of national security. In the US, the NSC was created in 1947 as the president’s principal forum for considering national security and foreign policy matters. It is chaired by the president and its regular attendees include the vice president, secretaries of defence, state, treasury and homeland, chairman joint chiefs of staff and director of national intelligence. It has become the president’s principal arm for coordinating between domestic and foreign policies and across federal agencies. Time has shown that this forum has enabled the president to make informed policy decisions.

In our own neighbourhood, India’s prime minister Vajpayee established an NSC in November 1998, six months after the South Asia nuclear tests, and one month after Gen Karamat had proposed the idea in Pakistan. Since then, India’s NSC has functioned regularly on all matters relating to the external and internal security of India, with key union ministers and military leaders in attendance. Five NSAs (three with diplomacy and two with intelligence background) have served the country. The NSC has a three-tiered structure, comprising a strategic policy group, an advisory board, and a joint intelligence committee.

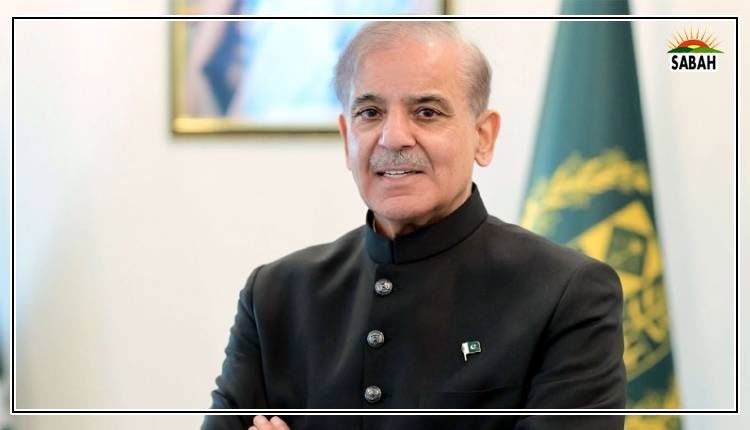

Pakistan can learn from these and several other examples where national security interests have been better served by institutionalised decision-making. Given that we have border security issues with our neighbours to the east and west, and with the forces of terrorism raising their head again, the next elected government needs to consider setting up a fully empowered NSC, chaired by the prime minister, and also appoint an NSA, so that serious challenges to Pakistan’s national security can be addressed collectively and more effectively.

The writer, a former foreign secretary of Pakistan, is chairman Sanober Institute Islamabad.

Courtesy Dawn, January 21st, 2024