SCO’s future ۔۔۔ Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry

ON Oct 15-16, Pakistan will host the heads of government meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. It would be an occasion to review the SCO’s progress towards fulfilling the promise with which it started out 23 years ago. The SCO evolved from the Shanghai Five, which was established in 1996 by China, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. It assumed its name when Uzbekistan joined in 2001. By 2017, India and Pakistan also joined it. Iran came along in 2023, and Belarus a year later.

Given that the SCO membership represents nearly 80 per cent of the Eurasian landmass, 40pc of the world population, nearly 30pc of global GDP, and a significant share of oil and gas reserves, euphoria surrounded it initially. It was conceived as a land bridge between Asia and Europe. This led to misgivings in the West, which started viewing it as a strategic push by China and Russia against the US-led West and West-dominated global institutions. Last month, the Council of SCO Heads of State in Astana, Kazakhstan, further stoked Western concerns by calling for a “new democratic and fair political and economic world order”. In 2022, the Samarkand meeting of SCO heads of state had called for a gradual increase in the share of national currencies in mutual settlement of SCO members, though this did not gain much traction.

That said, the West would not be too concerned because several SCO members, particularly India, continue to have close economic ties with the US and Europe. In fact, of late, India has been seen downgrading its participation in SCO activities. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi stayed away from the Astana summit. India also shifted the SCO summit it hosted last year to a virtual format. There are doubts regarding the Indian PM’s participation in the heads of government meeting that Pakistan is hosting next month. In an article published in Nikkei Asia, scholar Brahma Chellaney observed that India seems to be having “second thoughts” about its involvement in SCO, mainly because of the latter’s “anti-Western orientation”, which is at odds with the pro-Western tilt of Modi’s foreign policy.

Another dynamic at play is India’s tendency to allow its bilateral conflicts to cast a shadow on the organisation. India’s conflictual bilateral ties with China and Pakistan are hampering its own proclaimed priorities in SCO: regional connectivity and eradicating terrorism. It has also impeded efforts to align SCO states in areas of common interests. India’s approach runs counter to the ‘Comprehensive Action Plan (2023-2027) for Implementation of Long-Term Good Neighborliness, Friendship, and Cooperation among the SCO Members’ that was adopted in Samarkand in 2022.

India has been seen downgrading its participation in SCO.

Apropos China, India has entered into a needless competition for increasing its influence in the Central Asian Republics, and is seeking to counter Chinese influence in regional connectivity projects. In an article published on the website of the Observer Research Foundation by its vice president in July, it was alleged that Beijing had used the SCO to “pursue its hegemonic interests rather than providing any gains to the CARs”. India also opposes China’s BRI projects, particularly CPEC.

As for Pakistan, India never tires itself of hurling baseless allegations of cross-border terrorism against it, even though it is India which has mobilised state operatives to carry out assassinations in Pakistan. India’s hostile approach towards Pakistan seems to be guided by what Ajit Doval terms “offensive defence”. This aggressive Indian tactic has undermined the work of SCO’s most im-

portant Tashkent-based mechanism, the ‘Regional Anti-

Terrorist Structure’. India has mostly used the SCO forum for point-scoring aga-inst Pakistan. When Pakistan’s foreign minister visited Goa for the SCO meeting in May last year, the host, India’s external affairs minister, avoided meeting him, and, violating the ‘Shanghai spirit’, called him a “spokesperson of a terror industry”.

Owing to these reasons, not only India, but also China and Russia are focusing more on the expanded BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the UAE). India is also trying to become a self-proclaimed leader of the Global South. However, unless it changes its hegemonic attitude towards its neighbours, who all now face its hostility or overbearing intervention, no regional organisation in the Afro-Asian region, including SCO or BRICS, can deliver tangible regional economic cooperation in South Asia.

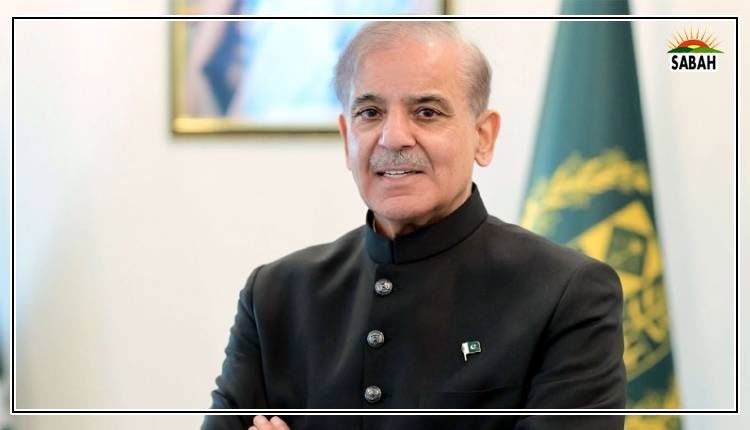

For Pakistan, the SCO meeting next month is an opportunity to reinvigorate the SCO platform and help sharpen its focus on promoting closer economic cooperation, particularly regional trade, connectivity, digital economy, and youth engagement.

The write is a former foreign secretary and chairman of Sanober Institute, Islamabad.

Courtesy Dawn, September 22nd, 2024