SC rules that the dissident members of the Parliament cannot cast their votes against their parliamentary party’s directives

ISLAMABAD, May 17 (SABAH): In a major development, the Supreme Court of Pakistan on Tuesday ruled that the dissident members of the Parliament (MPs) cannot cast their votes against their parliamentary party’s directives.

The court, issuing its verdict on the presidential reference seeking the interpretation of Article 63(A) of the Constitution related to defecting lawmakers, said that the article concerned cannot be interpreted in isolation.

The apex court wrapped up the hearing of the reference on Tuesday, which was filed by President Dr. Arif Alvi on March 21. The hearings continued for 58 days since its filing.

Questions asked in reference

Can defected parliamentarians be allowed to vote?

Will defected MPs vote be given equal weightage?

Can defected MPs be disqualified for life?

Other measures that can be taken to curb vote-buying?

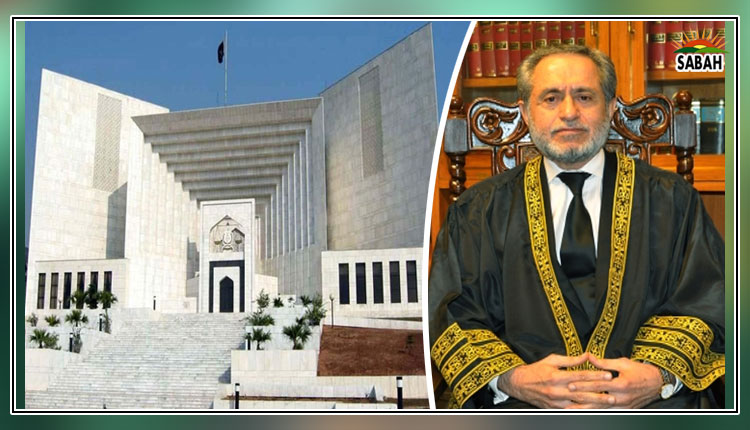

In the majority verdict of 3:2, Chief Justice of Pakistan Justice Umar Ata Bandial, Justice Ijazul Ahsan and Justice Munib Akhtar agreed that dissident members’ votes should not be counted when electing a prime minister or chief minister, casting a vote of confidence or no-confidence, or voting on a money bill or a Constitution (amendment) bill.

Meanwhile, Justice Mazhar Alam Khan Miankhel and Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail disagreed with the verdict.

In response to the first and second questions raised in the reference, the top court’s majority judgment said the votes of the defected parliamentarians would not be counted.

In response to the third question regarding the disqualification of members, the top court rejected the PTI’s plea, saving the lawmakers from permanently being barred from the Parliament.

In its opinion on the fourth question, the three judges said that it was the right time for the Parliament to legislate on lifetime disqualification and make laws in relation to curbing horse-trading.

Minority decision

The minority judgment — issued by Justice Mazhar Alam Khan Miankhel and Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail — mentioned that it did not agree with the majority verdict of the top court.

“The Constitution of Pakistan provides a complete code for parliamentary democracy,” the minority decision said, adding that in case a member defects from their party, the seat will be considered vacant.

The minority judgment maintained that the outcomes provided in Article 63(A) were more than enough.

The verdict, which was announced by the CJP Justice Umar Ata Bandial, stated that defection could “derail parliamentary democracy and destabilise political parties”. It also noted that the rights of political parties had been underlined in Article 17, while the objective of Article 63-A was to prevent defection.

The apex court called on parliament to determine the timeframe for the disqualification of a dissident lawmaker. It also did not give an opinion on one of the questions asked in the reference concerning the future measures that can be taken to prevent defection, floor crossing and buying.

Earlier on Tuesday the five member larger bench had reserved the verdict on presidential reference seeking its interpretation of Article 63-A of the Constitution, which is related to the disqualification of lawmakers over defection and announced to announce the verdict at 5:30 PM on Tuesday.

A five-member bench headed by Chief Justice of Justice Umar Ata Bandial, and comprising Justice Ijazul Ahsan, Justice Mazhar Alam Khan Miankhel, Justice Munib Akhtar and Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail, completed proceedings of the case on Tuesday.

The first hearing of the case took place on March 21 by a two-member bench, after which CJP Bandial constituted a larger bench to hear the matter, which took over news and public discourse in the country after at least a dozen members of the then ruling PTI, who were staying at Islamabad’s Sindh House, came out in open defiance of their party on the issue of the no-confidence motion submitted by the joint opposition against then-premier Imran Khan.

Main questions in the reference

Will “dishonest” MNAs be allowed to vote?

Will the defecting members’ vote be counted, given equal weightage?

Will the defectors be disqualified for life?

Measures that can be taken to prevent defection, floor crossing and vote-buying

During Tuesday’s hearing, PML-N lawyer Makhdoom Ali Khan submitted his detailed response to the court and asked for more time to present his arguments. He maintained that the situation had changed and he needed more time to seek instructions from his client.

Newly appointed Attorney General for Pakistan Ashtar Ausaf Ali also completed his arguments during Tuesday’s hearing. At the last hearing, Justice Bandial had expressed his disappointment over the AGP’s absence.

Taking the rostrum, Ashtar Ausaf Ali said that questions pertaining to public interest or the law could be raised in a presidential reference.

“Is the question asked [under] Article 186 not related to the formation of the government?” the chief justice asked. Article 186 is related to the advisory jurisdiction of the apex court.

The AGP replied that the president had never sent such a reference in the past over similar incidents, and urged the court to also view the reference within the context of the past.

Justice Ahsan remarked that the president did not need to seek legal advice from the attorney general before filing a reference. According to Article 186, the president can send a reference when a legal question arises, he pointed out, asking whether the AGP was disassociating himself from the presidential reference.

“I haven’t received any instructions from the government,” Ausaf replied, adding that he would aid the court in his capacity as AGP.

At one point, Justice Ahsan asked whether the AGP was trying to imply that the presidential reference was not admissible. “Are you suggesting that the reference be sent back without providing an answer?”

Justice Akhtar also recalled that the former AGP had declared the reference to be admissible. However, as the AGP, you can also present your stance, he said.

The AGP said that the reference was filed on the advice of former prime minister Imran Khan. He also clarified that he was presenting his stance, adding that the former government’s lawyers were present to do the same for them.

Ausaf stated that President Arif Alvi should have sought the opinion of legal experts before filing the reference. “If the opinions differed, then the president could have sent the reference,” he said.

Here, CJP Bandial said that several hearings had been dedicated to hearing the presidential reference. Articles 17 and 63 of the Constitution both talk about the rights of political parties while the latter protects these rights, he observed.

The CJP pointed out that the reference was filed in March and the court had been hearing it for a month-and-a-half. “Don’t focus on technical matters because things have proceeded beyond the point of whether or not the reference is admissible,” he told the AGP.

AGP said that this was a constitutional, not a technical matter. He also argued that the apex court had to keep in mind the rights of workers and political parties.

He explained that the procedure for taking action against dissident members was underlined in Article 63-A, adding that the appeal against the sentence would be taken up by the apex court.

He also argued that a lawmaker was not automatically de-seated when disqualified under Article 63(1). The lawmaker is issued a show-cause notice and asked to provide an explanation, he said. “If the party head is not satisfied, he can send a reference against the dissident lawmaker,” Ausaf added.

At one point, Justice Mandokhail asked whether the president had ever raised this issue during his annual speech in parliament. He also wondered whether any political party had ever taken steps to seek the interpretation of or amend Article 63-A.

The attorney general replied that after facing defeat in the Senate elections, the former prime minister (Imran Khan) did not issue any instructions to lawmakers.

He went on to say that Imran had issued a statement before seeking a vote of confidence from lawmakers in March 2021, in which he said that lawmakers should make a decision based on their conscience.

Imran Khan said that if he does not secure the trust vote, he would go back home, the attorney general said.

Justice Ahsan observed that issuing directions was up to the party head. “He (Imran) was also the prime minister when the no-confidence vote took place,” he said.

Ausaf responded by saying that the former prime minister had backtracked on his earlier stance, which led to Justice Ahsan asking whether it was unheard of for the prime minister to change his instructions.

“The prime minister has taken an oath under the Constitution. He can’t backtrack on his statement,” the attorney general said.

He went on to say that a lawmaker is elected by the people for a period of five years, following which lawmakers vote to elect the prime minister. “Lawmakers are answerable to the people,” he said.

The AGP also argued that lawmakers could vote to change the prime minister if the latter failed to fulfil the promises made with the people.

“Can’t laws be made to punish lawmakers who defect,” asked Justice Akhtar. Ausaf replied that they could be passed but parliament had not yet taken this up.

Justice Akhtar also questioned the basis on which the attorney general argued that Article 63-A was not applicable in this case. “Article 62, 63 cannot be applied until you amend the Constitution,” Ausaf replied.

“So far, you are saying that laws can be made,” Justice Akhtar observed, to which Ausaf replied that the apex court could not amend the Constitution.

“Only parliament can amend Article 62, 63 and 63-A,” he said. Concluding his arguments, he said that the Constitution had fixed a penalty for defection which could not be increased without making a constitutional amendment.

According to Article 63-A of the Constitution, a parliamentarian can be disqualified on grounds of defection if he “votes or abstains from voting in the House contrary to any direction issued by the parliamentary party to which he belongs, in relation to election of the prime minister or chief minister; or a vote of confidence or a vote of no-confidence; or a money bill or a Constitution (amendment) bill”.

The article says that the party head has to declare in writing that the MNA concerned has defected but before making the declaration, the party head will “provide such member with an opportunity to show cause as to why such declaration may not be made against him”.

After giving the member a chance to explain their reasons, the party head will forward the declaration to the speaker, who will forward it to the chief election commissioner (CEC). The CEC will then have 30 days to confirm the declaration. If confirmed by the CEC, the member “shall cease to be a member of the House and his seat shall become vacant”.

Ahead of its ouster, the PTI government had filed a presidential reference for the interpretation of Article 63-A, asking the top court about the “legal status of the vote of party members when they are clearly involved in horse-trading and change their loyalties in exchange for money”.

In the reference, President Dr. Arif Alvi also asked the apex court whether a member who “engages in constitutionally prohibited and morally reprehensible act of defection” could claim the right to have his vote counted and given equal weightage or if there was a constitutional restriction to exclude such “tainted” votes.

He also asked the court to elaborate whether a parliamentarian, who had been declared to have committed defection, would be disqualified for life. Alvi cautioned that unless horse-trading is eliminated, “a truly democratic polity shall forever remain an unfilled distant dream and ambition”.

“Owing to the weak interpretation of Article 63-A entailing no prolonged disqualification, such members first enrich themselves and then come back to remain available to the highest bidder in the next round perpetuating this cancer.”

The reference had been filed at a time when the then-opposition claimed the support of several dissident PTI lawmakers ahead of voting on the no-confidence resolution against then-prime minister Imran Khan. Eventually, the dissident lawmakers votes were not needed in Imran’s removal, as the opposition managed to stitch together support from government-allied political parties.

However, the role of dissident lawmakers was crucial in the election of opposition candidate Hamza Shehbaz as the Punjab chief minister who bagged 197 votes, including from 25 PTI dissidents.