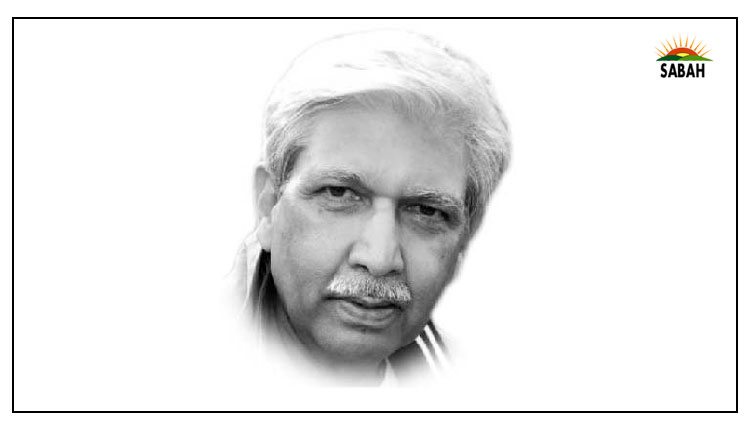

RIP Sartaj Aziz…Khurram Husain

ONE by one, those with a memory, and those who played a critical role navigating this country through the many crises it has passed through, are leaving us. The last few days have seen Sartaj Aziz and Riaz Khokhar pass away, taking with them a treasure of memories, reflections and much more, from so many critical episodes in our history.

I never knew Riaz Khokhar sahib, and it is my loss for not having familiarised myself with him. But I met Sartaj Aziz sahib on a few occasions, followed his work, attended an event in which he was a featured speaker in Washington, D.C. when he was national security adviser back in 2013, and recorded a long detailed, probing interview with him back in 2007 and again in 2013 shortly after the elections.

Sartaj sahib was solid, serious and wore an austere countenance. The closest to a smile I saw on his face was a brief, short smirk. But far more than his personal characteristics, it is the life trajectory that he carved out which tells a remarkable story.

He was an outsider in economic management circles when he landed as minister of state for agriculture in the Junejo government. Economic management in Pakistan was in the grip of a small cabal of civil servants in those days, a tightly knit network of handpicked men around Ghulam Ishaq Khan. These men circulated between all key positions involved in managing the countrys economy: finance minister, deputy chairman Planning Commission, chairman Wapda, governor State Bank of Pakistan.

These were also serious men, of very high calibre, including people such as V.A. Jaffery, A.G.N. Kazi and H.U. Beg. It was quite the norm for civil servants to run with their initials and surname in those days.

Ranged against them in virtually an adversarial role were the outsiders, or those who had served in international agencies and were returning to Pakistan with new, and different ideas of how to run a country. Among them was Mahbub ul Haq. Another, younger one, was Sartaj Aziz.

The GIK clique believed in a centralised economy, where the state would preside over all economic activity, sometimes as a direct owner of productive assets, at other times administering the prices or setting the terms of entry into any given field. They were mistrustful of private capital, but not hostile to it. They loathed bankers, at least the private variety, and had strong views favouring import substitution, protection of the domestic market and its producers who needed a strong, paternalistic power watching over them in their view.

Sartaj sahib was among the newcomers who believed the country needed to change. It needed to embrace markets, not smother them. It needed to open up foreign trade, move away from import substitution towards exports, and lose its fear of imports. Mahbub ul Haq and Mohammad Yaqub at the State Bank were among these individuals too, although the former was not exactly a newcomer.

He got his chance to start making a difference in 1985 as a junior minister in the Junejo government, but the limited space that the government had is well known. He finally got his chance when he was tipped to be finance minister in the first Nawaz Sharif government of 1990.

Pakistans first reform-minded budget was passed in that year. Import tariffs were slashed massively, and a domestic general sales tax was introduced to replace the revenues that previously had come from the high customs duties on all imports. Those years saw the first privatisation (of Muslim Commercial Bank that we now know as MCB), the inauguration of treasury bill auctions as the way to raise government debt, and the first serious advancement in private power generation projects (Hubco), lessons from which were later incorporated into the Private Power Policy in 1996. Those years also saw the beginning of the Foreign Currency Deposit scheme, which eventually grew so large it would cast a shadow on the viability of Pakistans external sector.

The decade of the 1990s saw such momentous changes in the economy and lifestyles that it is sometimes difficult to convey the full impact of these changes to the younger generation. These were the years when the first mobile phones appeared in the hands of private citizens, the first time foreign TV channels including CNN and MTV could be viewed in Pakistani homes. It was the first taste of foreign brands for many as shopping malls sprouted in major cities, like Pace in Lahore or Park Towers in Karachi. Foreign currency could be purchased without having to have your passport stamped, and so on.

All this flowed from the changes that rolled on from the earliest reforms pushed by Sartaj sahib. But there was a darker side: the country was becoming addicted to imports and its ability to pay for these imports was being hollowed out. Along with all the lifestyle changes, there came into our lives the rolling, endless trials and discussions around debt, default and devaluation.

Sartaj sahib was finance minister when the nuclear detonations happened in 1998. He was blamed for the decision to freeze foreign currency deposits and departed from the position shortly thereafter to take charge at the foreign ministry. Much later, he would argue in his book that there was no other option. He initiated massive changes in the life of the country. But how the country fared after that, lurching from one balance-of-payments crisis to another, was also part of the changes ushered in by him. During his years in service, he was right to point out that Pakistan could not afford to ignore the market realities engulfing the world. But Pakistan has yet to learn how to make these market forces work to its own advantage. Perhaps that is one lesson to draw from Sartaj sahibs departure, though I fear it might be too late now.

Courtesy Dawn