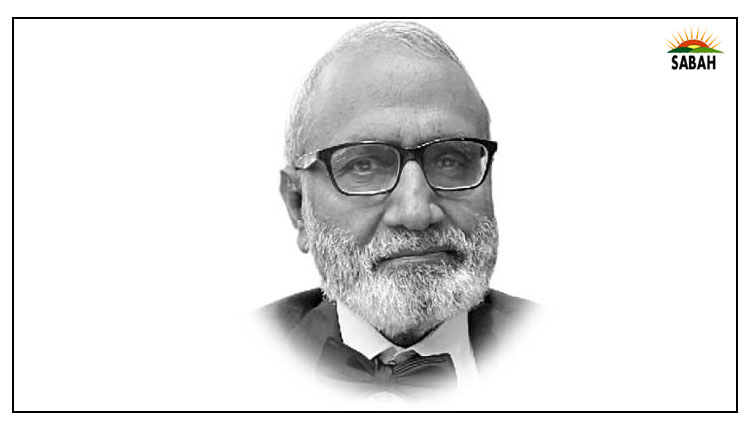

Politics and case pendency…Dr Pervez Tahir

In a democracy, politics is supposed to serve the people, and the courts are there to do justice between the people and vis–vis the state entities. Chapter 2 of the Constitution on Principles of Policy relates to the promotion of social and economic well-being of the people. It requires politicians to report annually on their observance and implementation and courts to ensure inexpensive and expeditious justice. Since April last year, however, political cases have preoccupied the courts, especially the superior judiciary, at the expense of the people. The political class has deviated from the responsibility to report to the Parliament the progress on the Principles of Policy. The judgement announced by the Supreme Court on Wednesday on the elections date of the Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assemblies has created more controversy than resolving the issue at hand. There is every likelihood that further litigation will follow. During the hearing, an effort by CJP to bring the polarised parties together did not succeed. The CJP agreed with Mr Farooq Naek, representing the PPP, that the courts should not interfere in political matters. Naek admitted that the judicial activism started in 2007 was giving way to judicial restraint.

During the incumbency of the present CJP, the number of pending cases has decreased from 53,624 to 52, 239. Progress there is, but it is extremely slow. Like in all other spheres, the access to justice became a serious concern only after a donor-funded programme was launched in 2005. The IT Directorate producing and communicating the data on pending cases on a regular basis owes its existence to the same programme. A hefty sum of $354 million was added to the external debt under the Asian Development Banks Access to Justice Programme (AJP). Among other things, it aimed to provide security and ensure equal protection under the law to citizens, in particular, the poor. Working on the well-known principle of justice delayed is justice denied, the AJP focused on the enforcement of rights when infringed in a reasonable time. Under this programme, the Law Commission Ordinance 1979 was amended to provide for a restructured and better mandated Law and Justice Commission. The National Judicial Policy Making Committee was also formed. Measures were taken to develop human resources for court administration and case management. As a result, the Supreme Court brought the pendency down from 80,000 cases in 2005 to 19,055 cases by 2008. It is obvious that significant reduction in pendency improves the confidence in judiciary. The recent upsurge in political cases may put the clock back.

It is about time that active consideration is given to the setting up of a constitutional court with jurisdiction over constitutional and political matters, besides judicial review of legislation. The proposal formed part of the Charter of Democracy agreed between PML-N and the PPP in 2006. It was not included in the the 18th Amendment. Politics has not matured since, creating space for non-political actors. The dominance of a single centralised institution and its proclivity to intervene beyond its mandate makes matters worse. And the now visible divisions in the judiciary reflecting the polarisation in the country is a cause for serious concern. Let the politically motived constitutional games be played in a separate arena and leave the Supreme Court and the High Courts to deliver rule of law. Ready access to justice is a key catalyst in sustained economic growth, something that has eluded our young and rapidly growing population. Learn from Trkiye, an inspiration for our leadership, that has one of the oldest constitutional courts in Europe.

Courtesy The Express Tribune, March 3rd, 2023.