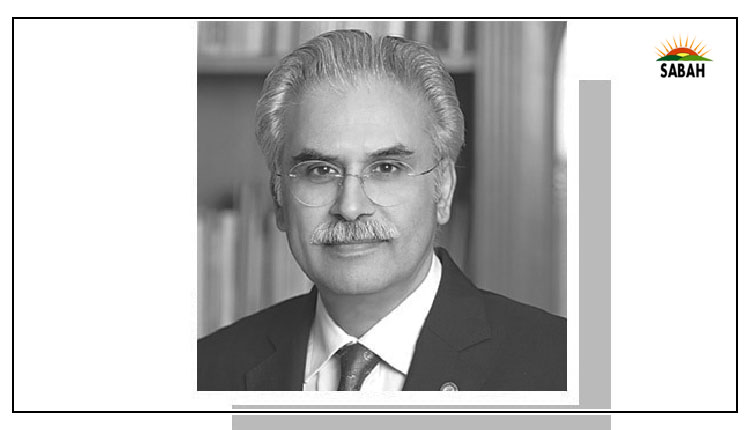

PHC and ‘qPHC’…Zafar Mirza

In medicine, we hold up autonomy as a professional lodestar, a principle that stands in direct opposition to discipline. Atul Gawande in The Checklist Manifesto How to get Things Right

WE had a few rickety tables and chairs dumped in a room in the Ministry of Health. In an internal meeting about office space, we wanted to get rid of this old and useless furniture. A fairly senior officer came up with a brilliant idea: send this furniture to the Basic Health Units and Rural Health Centres. Generally, people were fine with this suggestion. Ill spare you the details about the scene I made on hearing this suggestion.

Ministry officers were fine with this suggestion because this is generally how primary healthcare is perceived poor healthcare for poor people. The word quality is nonexistent in our PHC lexicon. This is why I have stopped using PHC altogether; it is qPHC, now and forever.

I would request that all of us use qPHC. Adding a q will always be a reminder of quality in PHC services and it would guide us in our relevant decisions about setting up facilities, organising trainings, managing procurements and supplies, upkeep of activities, monitoring, and above all, budgetary allocations. Improving quality also means being prepared to invest more money.

Without considering their quality, health services can be ineffective at best and counterproductive or outright lethal at worst. This is true for all health services. A cardinal principle in healthcare is, first, do no harm.

The Lancet Global Health Commission in High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution, concluded in 2018 that more deaths in low- and middle-income countries now occur as a result of poor-quality care rather than a lack of access to care. This is a hugely concerning inference.

PHC will not serve its purpose optimally as an initial point of contact and as a gatekeeper to advanced care at the secondary and tertiary levels if it does not live up to certain predefined quality standards. Speaking of standards, do we even have them at the PHC level?

In resource-scant environments, access usually supersedes quality. But the nature of healthcare is such that quality must be interwoven with access. Simple access with no attention to quality may be a feel-good factor, but it may also impede the provision of optimal service. I see many well-meaning healthcare providers assessing their impact only in terms of access and the utilisation of services not in terms of quality care, compliance with standards, patient satisfaction, or outcomes. That is, if they are assessing at all.

The outline of PHC as a cornerstone of sustainable health systems is enshrined in the historical Declaration of Alma Ata (1978), and the Declaration of Astana (2018). Both declarations were the outcomes of two international conferences on PHC held 40 years apart. Both conferences were co-organised by WHO and Unicef. The 2018 conference led to the development of the Operational Framework for Primary Health Care Transforming Vision into Action by WHO. This operational framework proposes 14 levers that can and should guide all actions and interventions to strengthen PHC. One of these operational levers is Systems for improving the quality of care.

This joint publication by WHO, the OECD and the World Bank in 2018 on delivering quality health services highlights the importance of developing a national quality strategy and/ or policy, and proposes that governments select a set of evidence-based quality improvement interventions in relation to four categories: the health system environment; reducing harm; improving clinical care; and patient, family and community engagement and empowerment. It explains in detail under each of these four categories how quality should be built into healthcare across the spectrum.

To start with, quality in healthcare must be taught to all health professionals, not just doctors, during their education and training. Currently, our curricula are notably deficient in this aspect. Once this foundation is laid, then in practice, clinical care should focus on processes and tools aimed at ameliorating effectiveness, including context-appropriate standards, pathways, protocols, checklists, standardised clinical forms, and clinical decision support tools. Improvement is an ongoing process that can help identify needs, such as clinical audits and morbidity and mortality reviews.

In Pakistan, since the emergence of the provincial healthcare commissions the latest being in Balochistan, and the Islamabad Healthcare Regulatory Authority standards in healthcare are increasingly being developed and implemented, and compliance is being monitored. They have already started showing some impact in terms of improvement in healthcare.

For example, the IHRA has shown sizeable differences in compliance scores between the first and second inspection visits to 16 major health facilities in the Islamabad Capital Territory, both public and private. A disturbing observation is that the top three dramatic differences in improvements between visits were noted in private hospitals and the narrowest three differences were in public sector hospitals.

Likewise, notable improvements have been made in the operations of blood banks in Islamabad in terms of their adherence to standard operating procedures. Percentage improvements between visits by IHRA inspectors range between 10.29 per cent to 73.27pc in a mix of 15 private and public blood banks. A similar picture is emerging due to the work of the healthcare commissions. These are important developments and this is just the beginning. Quality improvement work in healthcare is an ongoing process and in Pakistan we have a very, very long way to go.

PHC can deliver up to 90pc of essential healthcare throughout the lifespan of an individual, and since PHC is the foundation of universal health coverage, it has to be qPHC.

Courtesy Dawn