Missing NSC ۔۔۔Ahmed Bilal Mehboob

August was an extraordinarily bloody month in Pakistan, indicating a precarious internal security situation. On Aug 23, a convoy of policemen belonging to the Elite Force of Punjab was ambushed by dacoits near Machka, a small town on the border of Sindh and Punjab. At least 12 policemen were killed in the attack. Although organised gangs of dacoits have long been operating in this riverine area — called katcha in local parlance — this was a rare premeditated attack on law enforcers, a sign of the deteriorating security conditions in the area.

Days later, several much larger and bloodier incidents of terrorism took place on Aug 26 in Balochistan, claiming the lives of over 50 civilians and security personnel in Bela, Musakhel, and Kalat. In Musakhel, terrorists apparently belonging to the outlawed Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) stopped vehicles on the highway and offloaded and killed 23 persons after identifying them as Punjabis through their national identity cards. An important railway bridge connecting Quetta with the rest of Pakistan was blown up in Bela.

These incidents, especially the ones in Balochistan, were extraordinary acts of terrorism. They had grave and broad geopolitical and geoeconomic ramifications, given the critical development projects being completed with the assistance of Chinese money and manpower in the area. These incidents also fitted neatly into the pattern of terrorism targeting CPEC projects.

The security establishment and the governments in the centre and Balochistan immediately sprang into action and conducted at least two high-profile meetings to take stock of the situation. The Apex Committee of the National Action Plan met in Quetta and was chaired by the prime minister, with the deputy PM/ minister of foreign affairs, chief of army staff (COAS), federal ministers for planning, interior, commerce, information and EAD, chief minister of Balochistan, key provincial ministers, provincial secretaries, commander Balochistan corps and senior civil, police, intelligence and military officials in attendance.

COAS Gen Syed Asim Munir later also presided over a Corps Commanders Conference at the Pakistan Army’s General Headquarters in Rawalpindi on Sept 3, where the top military brass reviewed the security situation in the country with a particular focus on the recent incidents of terrorism in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

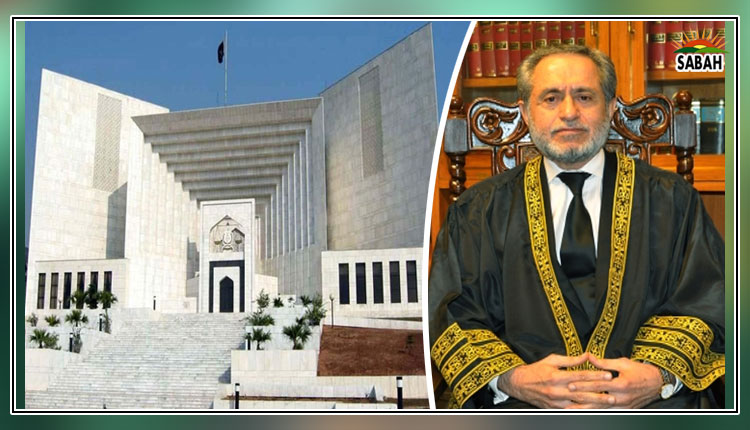

Conspicuous by its absence, though, was a meeting of the National Security Committee (NSC), which had almost always met whenever a serious security situation arose in the country in the past. The NSC, constituted in 2013 after the PML-N government returned to power, is supposed to be the highest executive forum in the country for discussing issues relating to national security. The council brings together the top military and civil leadership on one forum, and represents the first serious attempt by an elected government to institutionalise the consultative and decision-making process on national security.

The NSC membership includes the federal ministers for defence, foreign affairs, interior and finance on the civilian side, and the chairman joint chiefs of staff committee and the service chiefs of the army, air force and navy on the military side. In addition, other ministers and heads of the intelligence agencies almost regularly attend the NSC meetings on special invitation.

There has been a chequered record of NSC meetings since its formation. Despite the fact that then-prime minister Nawaz Sharif was the architect of the NSC, he convened the least number of meetings in his truncated term from 2013 to 2017. He convened only eight meetings in total, which corresponds to an average of about two meetings per year. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi did much better; his NSC meetings tally was eight in a 10-month term, which would have translated to an average of 10 meetings per year. Imran Khan held, on average, around three meetings per year, whereas Shehbaz Sharif, in his previous term, held an average five meetings per year.

Lately, there have been signs that the NSC is being sidelined. It has not met even once during the current seven-month term of the PML-N-led coalition government, despite the fact that security challenges have increased substantially during this period. The government had created a separate National Security Division in 2013 to support the NSC. One wonders what this division is doing while the NSC has not been meeting.

Despite repeated pleas by various organisations to hold regular, monthly NSC meetings, no regular periodicity has ever been fixed by any government. Instead, the forum has met only in reaction to security crises. A parliamentary delegation’s visit to the UK’s National Security Council was surprised to learn that their

NSC met regularly every week under the chairmanship of their prime minister, even though the UK did not face any active security challenge at the time.

Almost all countries have a platform for civil-military consultation, with most such platforms known as a national security council. Usually, these councils are strongly supported by a secretariat and robust research wings and think tanks. What Pakistan needs, in view of its mounting security challenges, is not to cut down on NSC meetings but to reinforce the intellectual infrastructure of the National Security division, as originally envisaged for our NSC by the late Sartaj Aziz, who had been serving at the time as the national security adviser to the prime minister. The NSC should meet regularly, at least once a month, and not just in reaction to specific security-related episodes but for active review of the broad security environment, fully supported by well-researched reports. The NSC must also discuss the broad contours of civil-military relations in Pakistan to de-stress any situation before it turns into a crisis, like it has repeatedly happened in the past.

Currently, the NSC is constituted through an executive order, but it may be worthwhile to enact a law to give stronger legal moorings to this body. Lastly, the NSC should be a consultative forum and not a decision-making body, as decision-making in a parliamentary democracy is the prerogative of the elected cabinet of ministers only.

The writer is the president of Pakistan-based think tank Pildat.

X: @ABMPildat

Courtesy Dawn, September 7th, 2024