Mass extinction…Aisha Khan

THE end of the 28th session of the Conference of Parties in December 2023 moved the needle forward on climate action but not at the pace needed to avert the sixth mass extinction. As eco-anxiety grows and optimists try to rationalise slow progress, with the inherent constraints of multilateral processes, the clock keeps ticking, reminding us of the perils and predilections of change and the timescale for keeping life systems alive.

The conversation on climate has become so jargon filled and technical in its approach that at times it loses sight of the here and now, becoming occasionally delusional and sometimes capricious.

Anatomically, modern humans emerged around 200,000 years ago in a process of evolution from ancestral Homo sapiens dating back six million years. Civilisation as we know it started around 6,000 years back and the advent of the industrial age began in 1850.

In the span of 173 years, humans have successfully landed on the moon but degraded ecosystems and destroyed the environment on planet Earth. Today, with advancements in science and technology, life expectancy has increased, progress in communication has transformed connectivity and creature comforts have enhanced life quality beyond imagination.

A single species is destroying habitats.

Ironically, all this has come at the cost of development that has turned into an existential threat. The main culprit for disrupting planetary balance are greenhouse gases.

As we enter 2024, it is important to put some things in perspective. The blame game at negotiations has gone on for 28 years. Perhaps it is time to take more individual responsibility and combine the two to save our species. A change in perspective may also alter thinking and help in finding solutions faster.

The dilemma facing the world is not only about how to reduce carbon emissions; in fact, it is more about how to retain existing lifestyles without compromising on quality or changing consumption patterns.

At COP28 Sultan al-Jaber earned flak for his statement that was interpreted to mean that giving up fossil fuels is tantamount to going back to the cave age. Seen in a broader perspective, perhaps it suggests that no one is quite ready yet to give up on lifestyles supported by fossil fuel. This applies to people from all tiers of society, across sectors, institutions and affiliations.

The outcry every year at climate summits is on the ascendant, and disappointment outshines hope. However, the fundamental question that holds the key to the climate conundrum remains unanswered. How much are we willing as citizens and societies to give up on current consumption patterns to embrace a low-carbon-footprint lifestyle? After all, it is possible to curtail supply by reducing demand.

Data demonstrates that modern food systems drive 90 per cent of deforestation and 60pc of biodiversity loss, and account for 70pc of the worlds use of freshwater. Overall, food systems alone contribute to over one-third of global greenhouse emissions. By going vegan the global population could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from food production by 28pc. And yet only 1-2pc of the world population is vegan.

The list of possible individual actions is as long as the list of commitments made by nations at climate summits.

Extinction is not a new phenomenon on planet Earth. There have been five previous mass extinctions. Many researchers argue that we are in the middle of a sixth mass extinction. The common denominator in all previous extinctions was a drastic change in the carbon cycle. The Permian-Triassic Extinction that took place 250m years ago was the largest mass extinction event in Earths history, affecting a range of species. The loss of biodiversity ended all life.

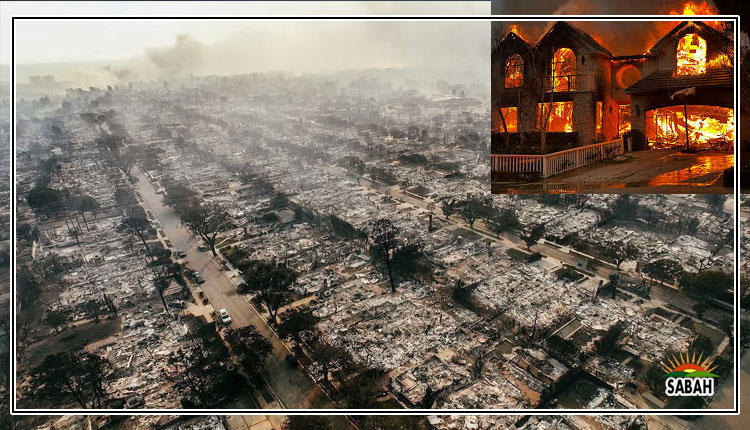

Today, the overgrowth and transformative behaviour of a single species is destroying habitats and unleashing a crisis. A European Commission modelling study shows likely extinction of 27pc of plants and animals by 2100. This continued disruption in the biosphere poses an extinction threat to one-half of Earths higher life forms by the turn of the century.

From all evidence, it seems that human beings are an aberration in the evolutionary process. They show scant respect for nature, are wasteful in their use of natural resources, degrade the environment, harm biodiversity, destroy the ecosystems that support them, and kill their own species. Rich, developing and poor nations all follow the same exploitative pattern of human behaviour.

The home truth is that the battle for human survival will not be won at the negotiating tables but by solutions provided by science and technology. Evolution will not stop with Homo sapiens. We might even be taken over by other forms of life in a new world order governed by artificial intelligence.

Courtesy Dawn