Life in Allai….. Zia Ur Rehman

Just looking at the recent cable-car incident might make you think it is just an isolated event. But it is more than that. Eight people, including seven schoolchildren, were stuck on that cable car over a river for 14 hours. This harrowing event shows just a little bit of what people in Allai go through every day.

Some two years ago, a research assignment took me to Allai, where I spent a few days in Pashto – the very same village where the cable-car incident occurred. This experience gave me a clear view of the many difficulties that shape the lives of the resilient residents of the valley.

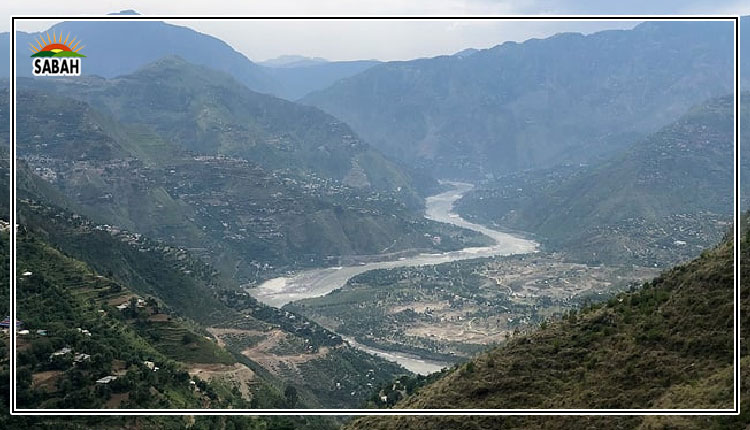

Allai, home to about 250,000 people, is one of Battagram district’s two tehsils in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The valley’s beauty is matched by towering mountains, but its remoteness poses challenges for basic infrastructure and services. Amid extreme poverty and underdevelopment, it stands as one of KP’s most deprived areas, where basic essentials like healthcare, education, and transportation are still lacking. During our trip, I recalled Maulana Qasim Mehmood, a religious scholar and our host from Pashto village, saying that “Allai still lags behind the rest of the country by 50-60 years”.

From Thakot’s bustling town, nestled along the banks of the Indus River, there’s a tough road that takes about 2-2.5 hours under normal conditions. But this road only goes up to Banna, which serves as the administrative headquarters of Allai.

After reaching Banna, the glaring reality sinks in: there is no proper road infrastructure to access the majority of villages scattered across the vast expanse of this valley, spanning thousands of square miles. The hard situation of the land makes it even more difficult for the strong people of Allai.

The journey from Banna to Pashto was nerve-wracking. For three to four intense hours, our rugged 4×4 jeep navigated steep mountainsides, crossed rivers, and scaled opposing peaks. I can’t remember how many mountains we crossed, but the constant fear of our jeep veering into the river below lingered. Mehmood, who was with us, told us that these perilous roads claim several lives each year – an undeniable reminder of the region’s beauty intertwined with danger.

Transportation options are limited for Pashto’s poor residents, who often choose walking over hiring 4×4 jeeps to reach destinations like Banna or neighbouring villages. During medical emergencies, patients, including labouring women, are tied with traditional wooden stretchers, involving one to two hours of trekking to the nearest road. They then rely on a four-wheel-drive vehicle to continue to the hospital in Banna. Dishearteningly, the hospital often lacks doctors, especially female staff, pushing the residents to travel hundreds of kilometers further to access medical care in the Battagram or Abbottabad districts. Tragically, such journeys often led to loss of lives and roadside births, according to the residents.

When a mechanic from neighbouring Battagram privately installed a chairlift a few years back, it drastically shortened what used to be a several-hour journey for nearly 500 people, including students, the sick, women, children, and the elderly. The nominal fee of Rs20 per person made this game-changing convenience accessible to all.

Amid the recent bad experience with the chairlift/cable car, a resident voiced the community’s need: “The incident was horrific, yet it underscores our pressing need. We demand the government’s support in installing good quality chairlifts across the Allai valley.”

The valley’s educational landscape mirrors its challenges: limited schools, especially higher education, resulting in low local literacy among the local population. The cable-car incident has also spotlighted the struggles faced by the area’s students. Only a few secondary schools for boys exist while there is a lack of higher education options for girls. The absence of a government college leads most students to halt education post 10th grade. A decades-long trend of enrolling children in madrassas, either locally or as far as Karachi, has emerged as an alternative to traditional education.

Much like other hilly regions in the north, a significant number of Allai’s residents are compelled to migrate to cities such as Karachi and Rawalpindi for employment opportunities as watchmen, daily wage workers, and in various odd jobs. This migration often entails leaving their families behind in the villages.

After the earthquake in October 2005 that killed around 3,000-4,000 people and injured thousands of others in Allai, people outside didn’t know much about what happened in the valley because landslides blocked the road to the valley and there were no electricity or phone connections for four days, say residents. And even though Allai was badly affected, the rescue and relief help and attention were focused on other places during those critical days.

In closing, Tuesday’s cable-car/chairlift incident serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need for change in Allai. On social media, residents are talking about how the government isn’t helping the valley develop. They are also criticizing the local landlords’ families and religious leaders from the JUI-F, who were in charge here for a long time.

It is time for authorities to step up and address the long-standing issues the valley’s residents face daily. One thing they could do is make Allai a new district like the people have been asking for a long time. They could also promote tourism in the area, steps that might make the valley grow and improve.

The writer is a journalist and researcher, who writes for The New York Times, among other publications. He also analyses conflict development in Pakistan for various policy institutes.

He tweets/posts @zalmayzia on X.

Courtesy The News