Judging the judges …. Ghazi Salahuddin

There is this gripping story of the Supreme Courts transformation from a measured institution of law and justice into a highly politicised body dominated by a right-wing supermajority, told through the dramatic lens of its most transformative year.

A bit confusing, isnt it? What do these words actually relate to? Well, I have taken this quote from the publishers blurb for a recent book on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. Its title is: Justice on the Brink: A Requiem for the Supreme Court. Its author is the highly respected law columnist for The New York Times, Linda Greenhouse. The book depicts, as one critic said, the struggle for the soul of the Supreme Court.

The issue involved here has shaken the civil society and the legal community of the United States. In June 2022, the US Supreme Court declared that the constitutional right to abortion, upheld for nearly a half century, no longer exists.

This debate is, of course, not for us. I have used it as a peg only to wonder if we may have similar studies on the conduct of the Supreme Court of Pakistan in these critical times and if those studies could generate serious, open debates on why and how certain judgments are made and what their social and political implications could be.

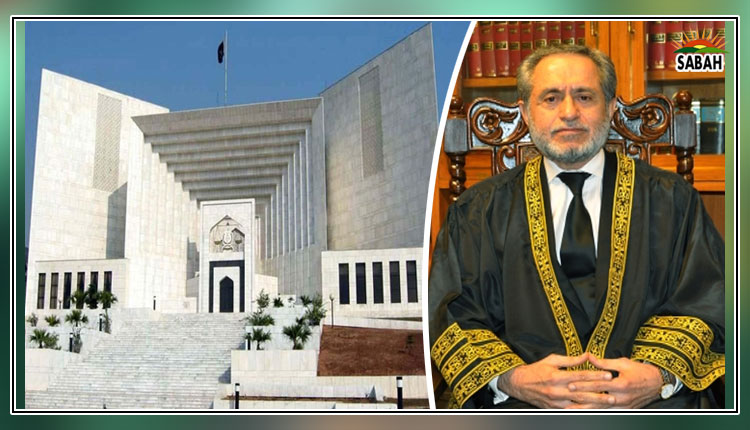

And this thought is particularly prompted by the Supreme Court-related headlines of this week. We already had some intimations about it but certain things have come to fore now that certify that this vital national institution is severely divided. Questions have been raised about the composition of benches that are formed to hear important and specific cases. There have been charges of bias and impropriety.

Yes, we are divided and dangerously polarized at all levels in our society. These passions could cast their shadows on the inner workings of our institutions. But because of the role that the higher judiciary is assigned to play in these critical times, one would expect the judges to remain, like Caesars wife, above suspicion.

After all, we are repeatedly reminded of how judicial lapses have played havoc with Pakistans destiny, beginning with that judgment of the Federal Court of Pakistan in the case of Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan in 1955. Then, there were other instances of how the doctrine of necessity was embraced to bow before military dictators, with just a few laudable exceptions. Bhuttos judicial murder remains a cautionary tale for our superior judges.

All that, we believe, was in the past. In the present circumstances, with things falling apart all around us, we may be tempted to expect that our higher judiciary would rise to the occasion and would somehow rescue us from our loss of hope in Pakistans democratic future. Among all national institutions, the higher judiciary is more respected and considered to be better endowed intellectually and capable of analytical and rational thinking.

(As an aside, I was not surprised when I learnt, through Geo fact-check, that retired Justice Saqib Nisar, the former chief justice of the Supreme Court who retired in January 2019, receives a monthly pension of Rs860,000.)

Anyhow, this weeks major concern for the nation were the suo-motu proceedings in the Supreme Court on delay in elections to the Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa assemblies. On Monday, Chief Justice Umer Ata Bandial, after deliberations in an anteroom, split a nine-member bench into a five-member bench. This was noted as a surprise move.

On Wednesday, this five-judge bench delivered a 3-2 split verdict. The majority judgment given by the chief justice with Justice Munib Akhtar and Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar directed the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) to consult with President Arif Alvi for polls in Punjab and Governor Ghulam Ali in KP so that elections could be held within the stipulated time frame of 90 days, though the ECP was allowed a barest minimum deviation from this deadline, in case of any practical difficulty.

The minority view, given by Justice Mansoor Ali Shah and Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhel, was that the suo-motu proceedings were initiated with undue haste and were unjustified. Observers noted that this controversy could have been settled with the formation of a full-court bench, which the chief justice did not do.

One question that was raised and not resolved was about the constitutional validity of how and under what conditions a provincial assembly could be dissolved. A number of other points were raised in the dissenting note. The chief justice did not explain why certain senior judges had not been included in the bench. The entire situation was rather confusing and did not inspire much confidence in the integrity of the judicial process.

In a parallel development on Tuesday, two senior judges of the Supreme Court, Justice Qazi Faez Isa and Justice Yahya Afridi took exception to a sudden change in the composition of their bench and summoned Registrar Isharat Ali for explanation. On Wednesday, in a nine-page judgment on this issue, Justice Isa said that people have every right to know how the administration of justice is undertaken.

Meanwhile, many questions are being raised with reference to audio leaks of conversations that supposedly include the voices of a superior judge and a prominent politician or have references to contacts with a judge. This and many other judicial matters are beyond my grasp because my understanding of the entire judicial process is very limited.

But what is obvious is that something is no, not rotten but perhaps out of tune in the state of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. We need some insight into why the superior judiciary seems to be under stress.

And, finally, the sixty-four-dollar question, at whatever cost in rupees, is whether elections in the two provincial assemblies will be held within 90 days, as directed by the Supreme Courts split judgment, or will the nation be confronted with some new, non-juridical emergencies?

The writer is a senior journalist. He can be reached at: ghazi_salahuddin@hotmail.com

Courtesy The News