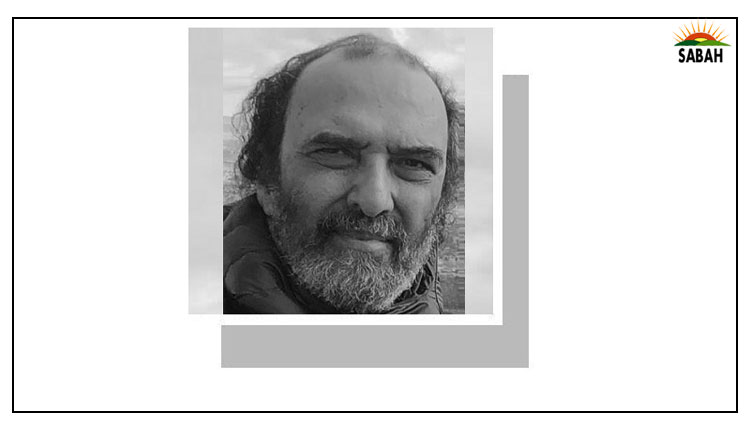

India, in sickness and in health …. Jawed Naqvi

IN the 1980s, a Bengali demographer had rudely but not inaccurately described four north Indian states as sick by giving them the acronym ‘BIMARU’, assembled with the first letters of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. ‘Bimar’ means sick or ailing, and the four states were singled out for the description for their critical social indicators, which were commensurate with their economic backwardness. When the UN officially launched the concept of ‘Human Development Index’ (HDI) in 1990, computing three parameters of long and healthy life, knowledge or schooling, and a decent standard of living, the BIMARU acronym was unwittingly reinforced though not confined to the four states.

Gujarat with its higher economic profile fares tardily in the realm of HDI. Haryana presents another example of the anomaly. The consolidation of the socially regressive Hindu revivalist BJP in these states may not be a coincidence. The southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu present the healthier aspect of India. The gap between the north and south is yawning.

The constitution describes India as a union of states, but the nuptial vows face a strained future should the parliamentary representation of states be changed by the twice postponed delimitation of parliamentary constituencies due in 2026. Indira Gandhi first froze the delimitation in 1975 for 25 years. It was further postponed for 25 years in 2001. What happens if the freeze expires in 2026?

Data scientist Nilakantan RS surveys the pros and cons of the unequal development of India in a recent statistics-laden book South vs North: India’s Great Divide. “Compare two children — one born in north India, the other in the south. The child from south India is far less likely to die in the first year of her life. She is less likely to lose her mother during childbirth and more likely to receive better nutrition. She will also go to school and stay in school longer; she will more likely attend college.”

The northern malaise gives India a bad name, not least in its health record.

The corollary, according to the author, is that compared to her counterparts in the north, the girl from the south is less likely to be involved in agriculture, and the odds of her securing employment that pays her more are greater. “This child will also go on to have fewer children, who in turn will be healthier and more educated than her.”

Should the success in population control be rewarded by a loss of political representation? How did the divide emerge? At independence, the southern states were not at any greater advantage against the north and were mostly indistinguishable from the rest of India.

“Today, the difference in development between some of the northern states and southern states is as stark as that between sub-Saharan Africa and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries,” says Nilakantan. He bats for sub-nationalism characterising the southern states as a reason for their relatively better development. In the author’s view, the sense of belonging in a localised geography was the glue which created the knock-on effects that accelerated growth in various spheres. A common purpose flows from the idea of sub-nationalism.

Let me digress with an illustration. In Dubai, one can see different Indian clusters like Malayalees, Tamils, Maharashtrians, Goans and Bengalis running their cultural clubs. I asked an insightful Indian journalist to explain the absence of a cultural platform for people from Uttar Pradesh. “UP thinks it is Hindustan,” he replied without demur. Nilakantan would agree. He says: “Uttar Pradesh is often propped up as a counter-example to states with high levels of sub-nationalism. There’s no sub-nationalism in that state. Even the name, Uttar Pradesh, is generic and was decided as an afterthought. It retains the colonial, short-version ‘UP’ for United Provinces and gives it a Hindustani twist. Unlike Tamil Nadu and Kerala, where linguistic identities transcended other sub-group identities, in Uttar Pradesh, loyalties to Hindi and Urdu served as proxies for religion.”

A major source of tension is the centralising urge of the Indian Union since its inception. In the 21st century, that reality of India’s democratic structure has assumed a cultural and political stranglehold over the country, rues Nilakantan. For example, resource allocation by the Indian Union — whether of finances or other kinds of resources that the Union collects from and shares back with the states — favours the north against the south. “The south is taxed more, both in absolute terms and on a per capita basis, but receives far less allocation in return, simply because its population growth is lower.”

The north-centric electoral politics is the bane of the south. The mismatch is stark. For example, a goal for the education sector, according to the National Education Policy of 2020, is to reach 50 per cent enrolment in tertiary education by 2035. “Some states in southern India have already exceeded that goal. Designing a policy whose 15-year goal has already been achieved is another way of condemning the south to the status quo while waiting for the north to catch up.”

The northern malaise gives India a bad name, not least in its health record. Its life expectancy at birth, the most basic measure of health of a population, is 69. That ranks it 125th in the world, behind war-torn countries like Iraq and Syria, and alongside Rwanda. “Even in South Asia, a generally poor region of the world, India ranks behind its neighbours Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal in this respect. Only Pakistan has a lower life expectancy at birth.”

India’s infant mortality rate, a more robust and critical indicator, according to Nilakantan, is also worse than most of its South Asian neighbours. Life expectancy at birth in India is low chiefly because too many babies die soon after birth, he says. It’s only Pakistan which does even worse than India in IMR in South Asia. A perpetual insult for south India to put up with.

The writer is Dawn’s correspondent in Delhi.

jawednaqvi@gmail.com

Courtesy Dawn, July 30th, 2024