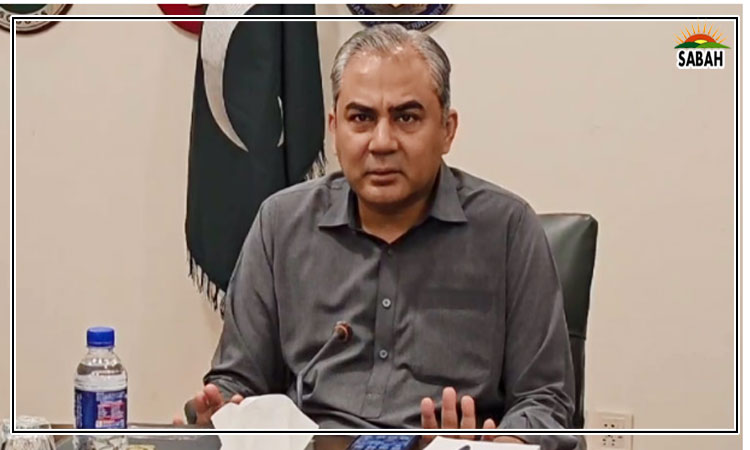

Ignoring climate thresholds…Ali Tauqeer Sheikh

PAKISTANS climate emergency is unfolding like a horror movie where each scene is more frightening than the last. We are constantly lurching from one climate disaster to another, with no time to step back and reflect on its implications for our society and economy. In the last 12 to 18 weeks alone, climatic changes have triggered a series of disasters, with heatwaves in March and April, tropical storms in June, and urban flooding in June and July. As if this were not enough, a new wave is now at hand: transboundary floods from both India and Afghanistan affecting Punjab and KP, torrential rains in the mountain ranges of Balochistan and Sindh, and landslides and glacial outbursts hitting Gilgit-Baltistan.

These extreme weather events (EWEs) highlight three interconnected undercurrents. First, IPCC projections that provided the scientific basis for the Paris Agreement in 2015 for stabilising global temperature warming at 1.5 to two degrees Celsius grossly underestimated the urgency of action for phasing out fossil fuels.

Second, the climate disasters in Pakistan are linked to each other and each EWE has cascaded or triggered a chain reaction defining new thresholds for the countrys climate vulnerability.

Third, the magnitude of climate-induced losses and damage is closely linked to weak climate governance. Pakistans policymakers continue to respond to climate disasters post-facto, and they have not really begun to translate new thresholds into policy guidelines and actions.

Parts of Sindh and Balochistan are approaching the limits of survivability.

Pakistan is not the only climate victim country. While Pakistans neighbours, particularly China, India and Afghanistan, too, are setting new records of heatwaves and flood levels, other regions of the world are also battered: heatwave spells in southern Europe, forest fires in the US (California), Canada and Siberia, and record-breaking droughts in the Horn of Africa are all setting new records. Nature is not willing to give us the time the climate scientists did in the Paris Agreement, and this will be echoed strongly in Dubai at the forthcoming Conference of the Parties in November.

Pakistan is standing at the crossroads of critical policy decisions to protect itself from these cascading events. Lets see how increasing temperatures and precipitation trends are intertwined and how Pakistan can take practical steps to strengthen its climate governance.

Heatwaves: According to the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD), new temperature and rain records were set in 36 cities in June. The sweltering conditions forced the Benazir Income Support Programme to suspend cash disbursements, trains were stopped as railway lines were reported to have melted, and electricity systems broke down in many areas because of the excessive heat or other reasons. Heatwaves in Pakistan have disrupted municipal services and school and hospital activity. They have also reduced work productivity and proved detrimental for the agricultural sector.

Parts of Sindh and Balochistan are approaching the limits of survivability as several towns from Jacobabad to Turbat are becoming unfit for human endurance. And yet, no institution is charged with keeping a track of heatwave-related data, nor are there any local governments to protect local populations. Provincial governments nevertheless have the mandate to revisit working hours and academic calendars, or to regulate labour rights in summer just as we have different working hours in Ramazan in many areas during the hot season. Stronger climate governance can reduce exposure to manageable risks.

In response to prolonged heatwaves, a small Spanish city has just developed a ranking system to manage heatwaves by monitoring temperatures and humidity levels. Developed with the help of the Atlantic Councils Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Centre, heatwaves have been categorised on a scale of one to three. Category 3 heatwaves will be the most serious and named in reverse alphabetical order, starting with Zoe, Yago, and Xenia in order to enable learning from each instance.

The Karachi Heatwave Management Plan, developed a decade ago, calls out for implementation by the newly installed city government, but Pakistan needs to adopt, like the Spanish city of Seville has, a national heatwave naming and categorisation system to save lives.

Tropical storms: The incidence of tropical storms in the Arabian Sea is increasing. Biparjoy set new records in June. It was ranked as a Category 3, or an Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm. It sustained high wind speeds of 160-180 kilometres per hour. With a 12-day life, it was the longest-duration cyclone recorded in the Arabian Sea. Pakistan was able to successfully track it on a real-time basis, thanks to important strides in our early warning system. For the first time in the countrys history, a large-scale evacuation operation was successfully undertaken, by evacuating 800,000 people.

Biparjoy caused severe heatwave conditions over Karachi and other districts of lower Sindh for several days, culminating in dust storms and widespread heavy rains in southern Sindh. It spurred a heatwave that continued for weeks. The PMD newsletter asserts that it also caused pre-monsoon rains in other areas of the country. Clearly, the monsoon system has been disturbed.

Fortunately, Biparjoy did not hit Pakistan, a major tragedy was averted and our ability to supply food, drinking water, medicines, latrines and supporting resettlement was not tested. The municipal administration, however, collapsed, and the military had to be called in to help with evacuation and logistical supplies. Sadly, two major political parties in the city were jockeying for Karachis mayorship, as the storm was nearing the coastline. All this while Pakistan still has to develop its local evacuation plans, undertake a dry run in some areas of Karachi and neighbouring urban centres, and strengthen local governments with emergency supplies.

District management authorities are not notified or functional, and the provincial disaster management authorities still do not have the ability to support local governments, which is their mandate and not raiding utility stores in emergency situations. The first line of defence against any climate disaster is none other than local governance institutions and community support groups.

It is time for us to stop sleepwalking and operationalise these new climate-induced thresholds to protect ourselves and the coming generations. We have the resources and technical capacities to prioritise small steps that can serve as building blocks for larger interventions and investments in climate governance.

Courtesy Dawn