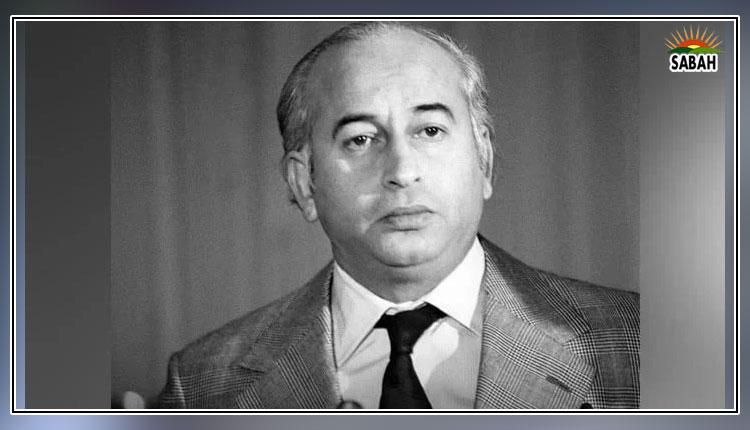

IFIs at a crossroads …. Zafar Masud

In October, as the world’s attention turns toward Morocco for the Annual Meetings of the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), it is an historic moment to contemplate the legacy of these two leading global lending institutions.

Over the decades, they have played a significant role in shaping the economic destiny of underdeveloped and developing nations. This review embarks on a journey to evaluate their achievements, successes, failures, and most importantly, their contributions to Pakistan and South Asia. We delve into areas such as infrastructure development, poverty alleviation, disaster management, and ponder on persistent questions about wealth distribution and the fundamental mission of these institutions: to uplift struggling economies and their institutions.

One of the most palpable contributions of the World Bank in Pakistan and South Asia has been in the realm of infrastructure development whilst the macro-economic stability and relief was ensured by the Fund.

Poverty alleviation is at the heart of the mission of the two institutions. In regions like South Asia, where a substantial portion of the population lives below the poverty line, the impact of the World Bank’s initiatives cannot be understated.

Microfinance projects, vocational training programmes and social safety nets have provided a lifeline for countless families, pulling them out of the abyss of poverty. Yet, the task is far from complete, and the roots of poverty run deep. Comprehensive strategies are needed to address the multifaceted nature of poverty in the region.

In a world where natural disasters wreak havoc, the IMF and the World Bank have played a pivotal role in disaster management. South Asia, with its vulnerability to earthquakes, floods, and cyclones, has been a beneficiary of the institution’s support in disaster preparedness, early warning systems, and post-disaster recovery efforts, and extended special financial financing facilities. These initiatives have saved lives and helped communities rebuild.

However, one pressing concern casts a shadow over these achievements – wealth distribution. Critics argue that, in some instances, the benefits of development projects have disproportionately favoured the privileged few or multinational corporations, rather than reaching the intended beneficiaries – the downtrodden communities.

A total of $42 trillion in new wealth has been created since 2020, with $26 trillion, or 63 per cent, of that being amassed by the top 1.0 per cent of the ultra-rich globally, according to an Oxfam report. The remaining 99 per cent of the global population collected just $16 trillion of new wealth. It suggests that the pace at which wealth is being created has sped up, and so has its concentration; as the world’s richest 1.0 per cent amassed around half of all new wealth over the past 10 years. This is a very alarming development.

South Asia is no different than the rest of the world. For it, the ratio of the average income of the poorest 10 per cent of the population to the richest 10 per cent is 6.5 per cent. In other words, the average income for the richest is more than 16 times the average for the poorest. The ratio is 7.5 per cent for Bangladesh, 8.6 per cent for India and 11.1 per cent for Sri Lanka. The ratio of the average incomes of the poorest 20 per cent of the population to the richest 20 per cent is 4.8 per cent for Pakistan and Bangladesh, 5.5 per cent for India and 6.8 per cent for Sri Lanka. The Gini coefficient – a measure frequently used to indicate the extent of inequality – is the worst for Pakistan: 29.6 as against 32.4 for Bangladesh, 35.7 for India and 38 for the world as a whole.

This raises questions about the effectiveness of monitoring mechanisms and the necessity for stricter regulations to ensure that the fruits of development are equitably shared amongst all segments of the society. This also emanates from the fact that the belief in the policies of the two institutions hovering around trickle-down effects on the economy as gospel perhaps needs a rethink. There certainly is a question mark on this approach and case studies like India where a bottom-up approach seems to have been working better than the traditional approach for growth must be considered in future policymaking.

As we convene in Morocco to celebrate the accomplishments of the IMF and the World Bank and consider their future, it is clear that the path forward is fraught with challenges. The wealth gap remains a critical issue, and these institutions must redouble their efforts to ensure that development benefits reach the marginalized communities that need them the most. Stronger regulations, transparent governance, and rigorous monitoring mechanisms are essential to this endeavour.

The ongoing shift towards sustainable development and climate resilience also presents a critical juncture. The World Bank must take the lead in advocating for environmentally conscious policies and investing in clean and renewable energy solutions while taking the private sector on board. Simultaneously, it must address the social dimensions of development, fostering inclusivity and reducing inequality with the use of technology in the public sector and digitizing the economy in their service delivery must be considered as mission critical in their support of South Asian nations.

The debate on the reconfiguration of these institutions must realize that nations fail not due to climate, geography or culture, but due to institutions. Sound institutions that allow virtuous circles of innovation, economic expansion, more widely-held wealth, and peace, result in lasting and sustainable economic growth and prosperity.

The world in the last decade has changed upside down. We’re now passing through an era of ‘first economic world war’, and ways and templates to address the issues of the world, particularly in emerging countries, certainly require soul-searching in this multipolar world of today. The new monetary policies set up at the global level over the past ten years require a rethinking of the balance between monetary and fiscal approaches, and a comparative, historical and transnational perspective is again essential.

Better engagement with new emerging players, like China, post the Ukraine war is the need of the hour for the Bretton Woods Institutions. At least 65 countries owe China more than 10 per cent of their external debt. This is the extent of Chinese integration into the global financial system which can’t move on without a collaborative and open-minded approach and dialogue for which the upcoming congregation in Morocco is an ideal opportunity.

The annual meetings in Morocco provide an invaluable opportunity for reflection and introspection. The World Bank and the IMF have played a pivotal role in shaping the global economic landscape and improving the lives of millions in Pakistan and South Asia. Yet, their work is far from finished. The challenges of poverty, inequality, environmental sustainability, and equitable wealth distribution demand a renewed commitment to the core mission of these institutions – to foster growth that is inclusive, sustainable and transformative – at the back of digitization and formalizing economies.

As the world watches Morocco, we must collectively aspire to a future where economic growth is not an end in itself but a means to uplift humanity, leaving no one behind, with new thinking, new perspective, new templates for fixing the complex landscape of emerging economies including those in South Asia.

The writer is a development and social-impact focused banker and a public-sector specialist professional. He’s currently serving as president and CEO of the Bank of Punjab.

Courtesy The News