Flying solo…F.S. Aijazuddin

THE US astronaut John Glenn — the first human to orbit the earth — was once asked how he felt hurtling through space in a capsule. His trenchant reply was: “How would you feel travelling in a machine assembled from 150,000 pieces of equipment, each procured by Nasa from the lowest bidder?” Over 200 million Pakistanis today are reliving his apprehensions. They are orbiting in a political void, led by a caretaker prime minister chosen from among the lowest political denominators.

Following the National Assembly dissolution on Aug 9, it took three days for Shehbaz Sharif (representing the outgoing government) and Raja Riaz Ahmad Khan (the still thrashing tail of a PTI opposition) to propose a name for the post of caretaker PM to an impatient president.

Names proffered by Sharif and Raja Riaz were unacceptable to the other. The person finally proposed to the president (and approved by him with alacrity) was Senator Anwaarul Haq Kakar, a comparatively unknown politician from Balochistan.

Raja Riaz justified the choice, saying: “We had earlier decided that the caretaker PM should be someone from a smaller province and a non-controversial personality. Our aim was to remove the sense of deprivation in small provinces.”

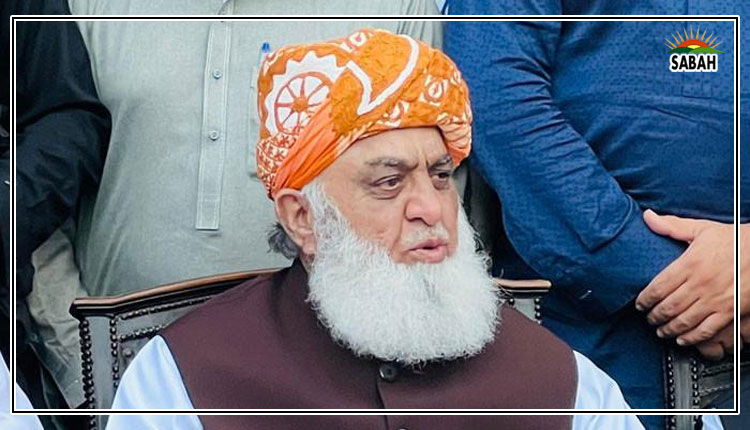

Will Shehbaz Sharif be content to play second fiddle?

Raja Riaz, a Punjabi, should have been more circumspect. Balochistan is the largest of Pakistan’s provinces. Geographically, it is one and half times the size of Punjab, two and half times the size of Sindh, and five times the size of KP. It is not small. It may have less of a population than the others but it deserves fraternal respect, not gratuitous condescension.

No one would doubt that the new caretaker PM is non-controversial. He owes his nomination to an establishment that breeds a stable of dark horses. The last such unexpected entrant was Usman Buzdar, former Punjab chief minister, appointed by then PM Imran Khan. In 2018, he appeared out of nowhere, survived in office for over 43 months until 2022, and then disappeared unlamented into oblivion.

No sooner had Kakar’s nomination been announced than his fellow politician from Balochistan Akhtar Mengal, chairman, Balochistan National Party-Mengal, shot a letter of remonstrance above the head of Shehbaz Sharif to his elder brother Nawaz Sharif in London. Mengal complained: “You have designated an individual as the caretaker prime minister whose appointment has shut the doors of politics for us.” He added more pointedly: “A solution is being sought by consulting the establishment instead of politicians.”

He reminded the elder Sharif — less in anger than frustration — of the ‘oppression’ suffered by the Baloch at the hands of military-led administrations from Gen Ayub to Gen Musharraf, which had not been forgotten nor, it would appear, forgiven.

History has a longer memory than politicians from Punjab. Mengal served as Balochistan’s ninth CM from February 1997 to June 1998, 10 years before Kakar entered politics. Seen as a militant Baloch, Mengal’s provincial loyalties attracted suspicion. He complained in an interview in 2013: “The Baloch militants consider me a traitor while the security establishment also treats me as an enemy.”

Mengal will not receive a reply from Nawaz Sharif. Like the astronaut John Glenn, Sharif’s prime concern is a safe re-entry.

Will Nawaz Sharif be welcomed by the very establishment that aborted his three earlier prime ministerships? Will he want to forgo the comforts of Avenfield House in London for the sweat, dust and drudgery of an election campaign in an insolvent Pakistan? Will his younger brother Shehbaz Sharif be content to play second fiddle after he has enjoyed being the master of his own one-man band in Islamabad?

In the closing days of the last government, Shehbaz admitted to having a close working relationship with the establishment. This came as no revelation. Five years ago, in 2018, he had told the Financial Times: “Where the military leadership needs to be consulted, we will consult them.” And he did not mean only on military or security-related matters.

A younger generation of voters might have noticed the last speech Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari made in parliament. Stressing the need for “political unity and reconciliation”, he appealed to key political figures, including his father Asif Ali Zardari and Nawaz Sharif, “to make decisions that would help create a conducive political environment, notably for Maryam Nawaz and himself”. His conciliatory speech was intended “to calm contending kings”. His entrenched elders though might construe it as premature patricide.

Today, Pakistan’s political future is again up in the air. No one knows for sure when elections will be held. Probably next year. However, those who have watched Shehbaz Sharif’s self-laudatory leave-taking can foresee the result. He intends to return as PM and then fly solo for at least five years.

Courtesy Dawn