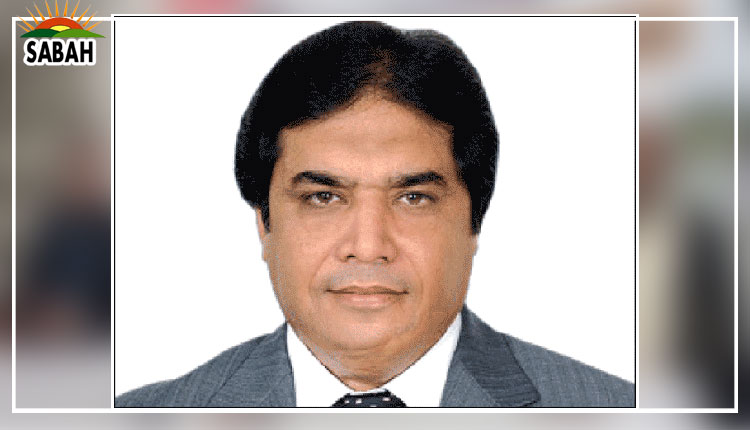

Facing the abyss ۔۔۔۔۔ Faisal Bari

THE 2023 census puts our population at 241.499 million and our growth rate at 2.55 per cent. This means we are adding some 6m people to the population every year.

For comparison, Finland, Norway and Denmark each have a population of less than the number of people we add to our population every year. The population growth rate had reportedly gone down to 1.9pc in the previous decade but has bounced back.

This, when most comparator countries, especially those in South Asia and others around us, have been quite successful in bringing down their growth and fertility rates substantially. Our failure is all the more stark and remarkable when we look at the figures for India (0.7pc), China (0.1pc) and Bangladesh (1.1pc).

Forty per cent of our children are malnourished. Our neonatal, infant, child and maternal mortality rates remain one of the world’s highest. We are one of only two countries, the other being Afghanistan, that has not been able to eliminate polio. In this day and age, we still lose many children to diarrhoea. We are not even able to provide safe drinking water to all our people.

Hepatitis and tuberculosis are uncontrolled and many health officials feel we are on the verge of an AIDS epidemic. One in four adults in Pakistan might be diabetic. Our health outcomes are a disaster, but more disastrous is the fact that we do not realise where we are, and irrespective of whether we realise it or not, we are not, as a polity, doing anything about it.

Twenty-three million, possibly more, of our five-to-16-year-olds are not in schools. We now have the world’s largest number of out-of-school children. We have not reached universal enrolment even at the primary level and dropout rates are high during the years of schooling.

Girls, children from rural areas, children from religions other than the dominant faith or minor castes, children from poorer families, all have a harder time accessing quality education in Pakistan.

The millions in schools, barring a minority who are enrolled in high-fee private or public schools, are getting an education of inferior quality. Our educational outcomes are a disaster, but again, more disastrous is the fact that we do not realise where we are, and irrespective of whether we realise it or not, we are not, as a polity, doing anything about it.

Pakistan is the world’s third or fourth most polluted country. Living in Pakistan, almost in any big city, means losing four to five years of life expectancy. Lahore tops the most-polluted city ranking the most often. But most of Punjab and many parts of Sindh have high environmental pollution levels too. This is also showing up in the increased incidence of disease.

The tragedy is that we do not even realise what we have done to ourselves.

All of this is not the result of neglect by one government or one party. It is the result of decades of deliberate policies which are an outcome of political economy settlements in Pakistan. Jaun Eliya captures this beautifully:

(I am very strange, indeed so strange that I have destroyed myself but have no regrets.)

The state’s role in population management, health, education, or environment are not considered important in Pakistan. The rich, elites, and politically and/or socially more connected groups have found ways of accessing these services through other means. For a majority, it is through the private sector.

Access to safe drinking water, quality education and health services are available to those who can pay for it. We have private schools that charge up to Rs70,000 per child per month. Even mainstream high-fee schools would be around Rs30,000 per child per month.

High-cost hospitals charge around Rs20,000 per room per night. If you number among those who can afford these costs, you might not be too pushed about the provision of quality health and education services for those who cannot afford them.

In other cases, significant groups of people have created their own separate and dedicated streams for the provision of these services. The army, navy and air force have their own school systems, universities and healthcare provision facilities. These are usually of decent quality and better than the services provided to the public at large through government schools, hospitals and/or public universities.

Right now, we are in the middle of economic and political crises as well. Some have called this moment a ‘polycrisis’. It is true that we are facing many issues at the same time. The economy is doing poorly.

Our political system is in a crisis as well. The crisis of governance is deep, institutional degradation is real, and trust deficit — between all — is also deep. But some crises are more long-term, deeper and more persistent.

An economic turnaround could potentially happen in a number of years. But political economy issues need far deeper reforms and a longer period as well.

Even if political economy reforms are in place and policies start addressing the dismal situation regarding the population, health, education and the environment, it will be a decade or more before we will start seeing any impact.

But as Jaun Eliya indicates, the tragedy is that we do not even realise what we have done to ourselves. We might have stabilisation with this or the next IMF deal, and elections might settle some things on the surface, but the deeper issues will remain.

They need far greater political, economic, social and institutional reforms and there is not even any conversation regarding them. The state of the nation’s educational, health, population and environmental services and outcomes tell us as much.

I do not know if people have seen the painting The Scream by Edward Munch. If you have not, you can search for it online. This is how we should be reflected in terms of where we are today. Will we realise what we have done to ourselves and try to change course?

The writer is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives, and an associate professor of economics at Lums.

Courtesy Dawn, November 24th, 2023