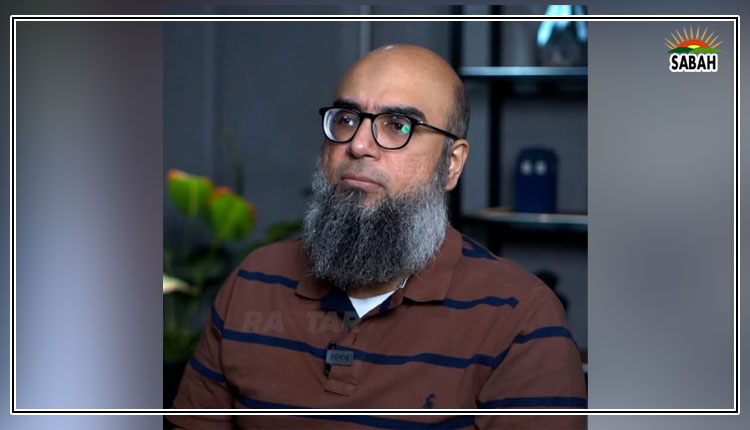

Dichotomous behaviour ….. Muhammad Amir Rana

PAKISTAN’S power elites are grappling with a ‘Jekyll and Hyde syndrome’, showcasing starkly different behaviour in their attention and actions. Their purported focus on fixing the economy is contradicted by their actual measures, and the same applies to their efforts in addressing political and security issues in the country.

Recently, an interesting piece by Shahbaz Rana in an English daily talked of the experiences of a British economist dealing with the power elites in the country. According to the writer, Stefan Dercon “had impressed Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif so much that he immediately hired him to help prepare a ‘home-grown’ economic plan. But while Stefan Dercon was holding meetings with Shehbaz Sharif, the premier’s financial team … was preparing a budget that would benefit those same elites and throw the country’s marginalised classes under the bus”.

According to the writer, Mr Dercon reached the conclusion “that the motivations of Pakistani elites would not allow the economic growth and development of the country to be prioritised”, and found “an underlying elite bargain for the status quo among powerful elite groups”, which, he said, comprised leading figures in politics, business, civil society, the military, civil service, intellectuals and journalists.

The full- and half-page advertisements by the federal and Punjab governments highlighting their tall claims about their first 100 days of achievements may reflect their desire. However, their practice of crushing the middle and lower classes of the country while obliging the power elites are a reflection of the Jekyll and Hyde syndrome. The latter term has been inspired by R.L. Stevenson’s famous tale of TheStrange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, in which the respectable scientist Dr Jekyll develops a potion which turns him into the evil Mr Hyde. This concept is sometimes associated with certain clinical personality disorders associated with mood swings.

The concept is also reflected in the dichotomous behaviour of our power elites. An excellent example is the Bollywood dark comedy Matru Ki Bijlee Ka Mandola. In this film, Pankaj Kapur portrays Harry Mandola, a shrewd businessman who wants to turn a village into a symbol of his success. He can only do so if the residents sell their land to the government at throwaway prices, so that it can be turned into a Special Economic Zone. Harry’s alter ego emerges when he is seen as intoxicated. In this state, he advocates for equality and an improved life for the villagers.

The primary objective of our power elites is to maximise their benefits.

Pakistan’s power elites often act like Harry Mandola. Their primary objective is to maximise their benefits, but when faced with public anger, they pose as reformers and engage experts. This is evident in their economic policies, which favour the elite while claiming to be for the benefit of the entire nation.

In the article referred to earlier, Dercon finds that “growth and development [are not] core motivations for the dominant political class or the military — and that economic policies are driven by a quest to retain power as part of a clientelist patronage-based state”.

Meanwhile, political analyst Muhammad Waseem sees the strength of the power elite in a dynamic political conflict in Pakistan, where all political actors are in accord with ‘establishmentarian democracy’. This concept refers to a system where the establishment, which includes the military and other powerful institutions, plays a significant role in shaping the political landscape. In his book, Political Conflict of Pakistan, Dr Waseem explains the conflict along four dimensions: the state’s conflict within, ethnicity, religion, and subaltern (non-conflict).

The power elites are playing with these four-layered conflicts and have defined the boundaries for insiders and outsiders. The insiders control power, while ethnic and sub-ethnic as well as religious minorities, including the Baloch, Ahmadis, Christians, Hindus as well as the Shia and Zikri sects are outsiders, according to this concept.

But gradually, power elites are losing their touch. The elites always relied on the conventional notion of cohesion: religion could provide the bond. However, the religious card has been exploited so often that it has lost the power of glue, and even a commoner understands what the real motives of the recently concluded TLP sit-in Islamabad were.

The economic policies of the power elites have failed to impress even the average global economist. Their political manoeuvring has lost its strategic edge, and their security measures are instilling more insecurity in the minds of the masses, raising serious concerns about the state of affairs in Pakistan.

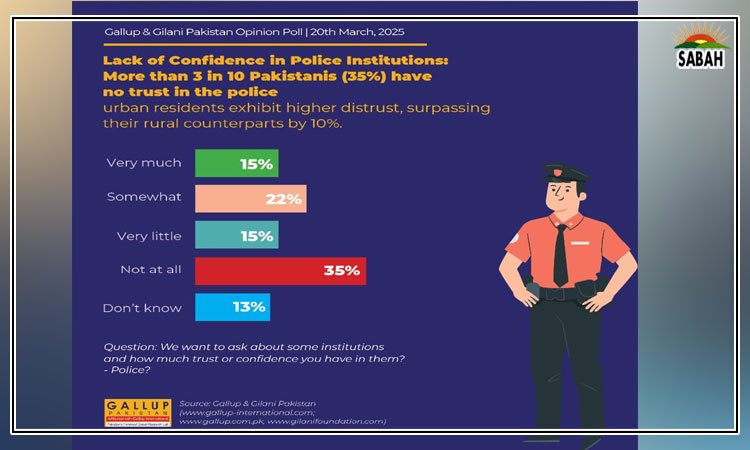

The power elites have already created a gulf between the masses and the state, and it may not surprise anyone that more and more people want to leave the country. Surveys suggest that most Pakistanis lack faith in the government and consider elections an exercise in futility.

Political analysts constantly discuss the country’s weakening social contract, but power elites have not changed the rules of the game and are using the same tactics to fix politics and the economy. Their actions have brought the country into a state of decline, but they have no empathy. They are solely focused on their personal benefits and are not ready to give up an inch of what has already been acquired. This stark reality may disillusion many about the current state of Pakistani politics.

In the final chapter of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Dr Jekyll explains his experiments as an attempt to separate the good and evil aspects of his personality. He initially enjoys the freedom of becoming Mr Hyde, but soon loses control over the transformations, which begin “occurring spontaneously”. Unfortunately, it is the evil nature of Mr Hyde that becomes more dominant and harder to repress.

The writer is a security analyst.

Courtesy Dawn, July 21st, 2024