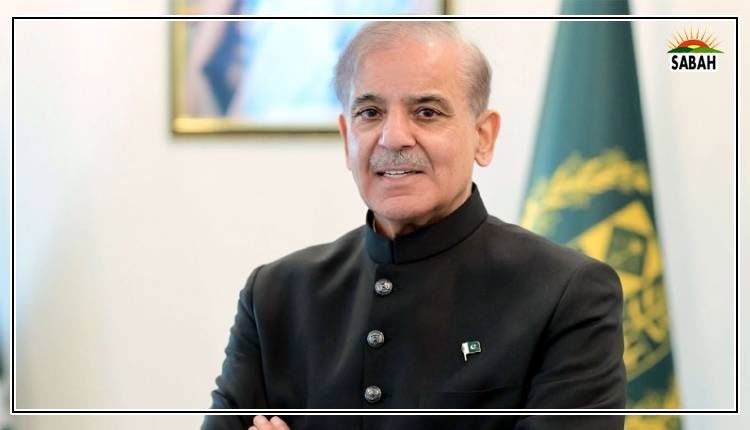

Debunking myths: the IEA monolith and Afghanistan transit trade …. Inam Ul Haque

We close this series with debunking the last two myths vis-à-vis IEA and Afghanistan.

Myth No 12. IEA is a monolith. Without deep socio-historic insight into Afghanistan’s segmentary politics, it is easier to consider the Islamic Emirate that evolved from the Afghan Taliban as a monolith. It would be useful to dissect IEA’s religious, ideological, political, cultural, tribal and ethnic profile to understand it well.

First religion and ideology. IEA mostly follows the Hanafi Islam, of taqleedi school of thought, steeped into the Deoband tradition emanating from the chain of Haqqani madrassas in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Briefly, Hanafi is one of the four widely practiced jurisprudence in contemporary Islam, following the fiqh (lawfare) of Imam Abu Hanifa (699-767 AD). Taqleed is the Subcontinent’s version of religious practice, emphasising ‘following’ the clergy as opposed to re-interpretation or ijtihad. Deoband, Saharanpur, UP, India is the alma mater for taqleed in the Subcontinent with pervasive religious influence. Its leaders played a leading rule in Muslim political organisation and education in the 1860s. Haqqani is the nom-de-guerre used by graduates of Darul-Uloom Haqqania, Akora Khattak, KP, Pakistan, and its affiliate madrassahs elsewhere in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Since its inception between Kandahar and Maiwand in eastern Afghanistan in 1990s, Taliban Movement has steered clear of Salafi Islam practised by some Afghan resistance groups (Harkat and Hizb) and Shia influences under Hizb-e-Wahdat. Its alliance with Salafist al-Qaeda, espousing universal appeal for Sharia-based revolutions, was a patron (al-Qaeda)-client (IEA) relationship, that remains tactical in nature, and is nurtured by a curious mix of Islamic brotherhood and the tenets of pashtunwali — the Afghan/Pashtun tribal code. In this universe, religious practice is subservient to tribal, specifically the pashtunwali ethos. IEA recalcitrance on girls’ education and female employment is a case in point.

Within the broader Movement, Kandahar the spiritual head of the Movement is the ideological mover and shaker under the venerated Maulvi Haibatullah Akhundzada, hence my repeated emphasis on religious diplomacy with Kandahar. Kandahar is ideologically puritanical and symbolic. Northern Afghanistan — Khowst, Paktia, Paktika, Nangarhar, etc — bordering Pakistan have remained under the influence of Siraj Haqqani et al. These are formidable fighters making up the bulk of IEA’s military power. Haqqanis voluntarily joined IEA during the 1990s and were not coopted under duress like many other groups. Hence Haqqanis yield influence and their distinct identity within IEA. Puritanical Kandahar and pragmatic Khowst share ‘the need to present a united front to the world beyond Afghanistan’ as an “existential compulsion”. They need to be seen on one-page despite the cited backgrounds and differences.

Second, ethnically the IEA, although predominantly Pashtun (95%), also has a sprinkling of non-Pashtun elements from northern Afghanistan, especially from the Uzbek, Tajik and Turkmen ethnic groups. IEA decided to penetrate northern Afghanistan around 2006 from Farah province, fanning into Nuristan, Badakhshan, etc.

Besides, IEA is also a conglomerate of disparate groups, like Central Asia’s IMU (Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan), China’s ETIM (Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement), TTP, al Qaeda, Arab fighters, Punjabi Taliban, etc following different ideological strands, and religiosity levels.

Third, culturally IEA is not steeped in equal measure into religious zealotry, as significant renegade elements from the erstwhile Soviet era mujahideen groups, criminals, highway men, brigands and disgruntled government employees form its rank and file. The Movement actually started against the immorality, excesses and cruelty of strongmen and their militias, who had divided Afghanistan into their fiefs after the Soviet pullout in early 1990s. They had established checkpoints all over and would exact taxes and levies and administer punishments. Led by seminary students, the Movement over a period incorporated all segments of Afghan society through negotiations, appeasement, motivation and use of force.

And in this all-male enterprise, there is no female cadre known, other than the female students of madrassahs inside Afghanistan.

Four, IEA mirrors Afghanistan’s tribal mosaic especially in case of its Pashtun cadre. Afghan tribalism emphasises loyalty, following, and the power of collective. Tribal identity is segmentary and results in weak political organisation among Pashtuns as a whole, therefore it is important to hold things together using religion as the much-needed glue. IEA is traditionally populated by clergy namely the Akhunds, the Mojaddedis, the Maulvis, the Sheikhs, etc. Haqqanis of Loya Paktia (grater Paktia) are mainly from Zadran tribe (Mezi subtribe) with their spiritual and military power resident in Pakistan’s north Waziristan District, warranting collaboration with Wazir, Daur and Mahsud tribes on the Pakistani side. Whereas, the Kandahar elite is ‘mainly’ from Hotak (Ghilzai) and Durrani tribes, collaborating with the Suleman Khel, Kakar and Achakzai tribes on Pakistani side of the Durand Line.

Five, politically the IEA has hardliners represented by scholars and clerics; and moderates including the comparatively liberal younger cadre. Whereas the elderly non-yielding conservatives see everything through a spiritual and Islamist prism, emphasising the virtues of jihad and disregarding modern life and its bounties; the younger moderates are more worldly, IT-savvy and image-sensitive. In this see-saw for power and influence, conservatives have the final word. So, in the final analysis, relative opening-up of the Movement to a semblance of modernity would be possible over time in mid to long-term.

Taliban Movement, like all movements, has a lifespan that should be granted, while understanding its compositional diversity, as discussed.

That brings us to Myth No 13. IEA can re-orient the Afghan Transit Trade through the Iranian port of Chabahar, cutting reliance on Karachi and Pakistan. Landlocked Afghanistan heavily relies on transit trade from Pakistan through five joint border crossings at Torkham, Ghulam Khan, Angoor Ada, Spin Boldak and Dand-e-Patan. The Afghanistan Chamber of Commerce and Investment’s first deputy head, Mohammad Yunus Momand recently claimed development of Wakhan Corridor and Chabahar Port as potential alternatives. India too seeks trade with Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia through Chabahar Port cutting off Karachi and Gwadar. IEA has reportedly committed a $35 million investment in Chabahar.

Whereas such attempts would betray Pakistan’s longstanding goodwill and concessions, it is easier said than done. A tilt towards a sanctioned Iran would compound IEA’s problems of international legitimacy and undermine its residual influence with Pakistan. It is also not possible in the near to mid-term, given that ATT through Pakistan is deeply entrenched in the bordering business elite. These Sunni Pashtun traders may find it hard to trade through a Shiite Iran, that uses leverages much more punishingly than a sympathetic Pakistan.

Courtesy Express Tribune