Dealing with the Taliban…Maleeha Lodhi

WHEN the Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan over three years ago, Pakistan’s policymakers assumed this would help to guarantee the stability of the country’s western border. That has long been a strategic compulsion given Pakistan’s troubled relations with India on its eastern flank.

But the assumption about securing the border with Afghanistan under Taliban rule turned out to be a strategic miscalculation. It did not take long for it to become evident that the Taliban takeover enabled the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan to reorganise, revitalise and then escalate cross-border attacks, posing a serious security threat to Pakistan. The Taliban’s unwillingness to take action against the TTP upended Islamabad’s expectation that Kabul would be responsive to Pakistan’s security concerns.

Successive reports by the UN Security Council’s Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team reinforced Pakistan’s assessment by the finding that the “TTP benefited the most of all the foreign extremist groups in Afghanistan from the Taliban takeover”. Its latest report of July 2024 says the “TTP remained the largest terrorist group in Afghanistan, with an estimated strength of 6,000-6,500 fighters”. It “continues to operate at significant scale in Afghanistan and to conduct terrorist operations into Pakistan from there”.

There was a significant surge in cross-border terrorist attacks by TTP last year and rise in casualties of law-enforcement personnel, which heightened the security challenge for Pakistan. In fact, 2024 was the deadliest year with the highest number of casualties in terrorist attacks in almost a decade.

Three-and-a-half years of talks on the TTP between Pakistani officials and Taliban authorities yielded little. Taliban responses ranged from asking for time to ‘manage’ TTP to urging Pakistani officials to talk to the militant group as well as offering assurances of resettling its fighters away from the border and asking for financial help to do this.

Neither side wants a breakdown in relations, so diplomatic re-engagement is a compulsion.

With their patience exhausted, Pakistani authorities began to adopt a harder line towards Kabul, also undertaking unannounced kinetic attacks on TTP sanctuaries and individuals in Afghanistan. Public statements by Pakistani leaders became tougher. Taliban leaders were asked to choose between the TTP and Pakistan. Military spokesmen held the Afghan interim government squarely responsible for “arming terrorists and providing a safe haven for them”.

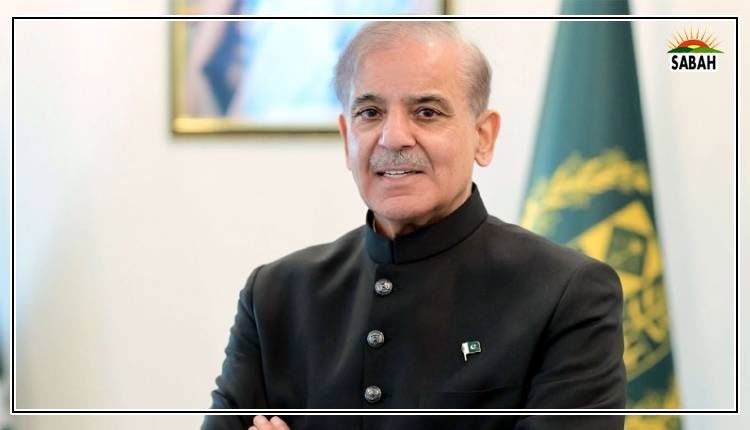

Last week, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif demanded Kabul take action to stop TTP from attacking and killing innocent people, calling that a red line for Pakistan.

This followed an audacious TTP attack on a border post in Makin in late December which left 16 security personnel dead and forced Pakistan to retaliate. Days later, on Dec 24, Pakistani fighter jets carried out air strikes against TTP hideouts in Paktika province. The Taliban authorities lodged an angry protest with Islamabad and claimed their forces retaliated by hitting several Pakistani positions along the border including in Waziristan. These armed clashes injected more tensions into an already strained relationship.

This at a time when Pakistan’s special envoy for Afghanistan Muhammed Sadiq was in Kabul holding talks with the Afghan Deputy Prime Minister Maulvi Abdul Kabir and other Taliban officials aimed at de-escalating tensions. Overshadowed by the air strikes, Sadiq’s visit marked an effort to reset ties with Afghanistan after over a year of coercive policy actions pursued by Islamabad.

These actions included, apart from unannounced air strikes (except strikes in April 2024 which were publicly acknowledged by Islamabad), transit trade restrictions and expulsion of illegal Afghan refugees from Pakistan. Kinetic actions are often referred to by Pakistani military officials as intelligence-based operations and aim to degrade TTP’s capabilities.

Coercive actions as a whole were designed to raise the costs for the Taliban of their non-cooperation on the TTP. These measures yielded limited results. Pakistani authorities then decided diplomatic re-engagement with Kabul was necessary to prevent a breakdown in relations, resuming dialogue after a year’s hiatus to explore possibilities for resolution of trade and security disputes. Both sides seemed keen to halt the deterioration in relations with bilateral trade and transit trade having precipitously declined over the past year or so.

Although the armed clashes and exchange of hot words between the two countries have put diplomatic engagement on pause, it is nonetheless expected to resume sooner rather than later. This indicates a tentative shift in Pakistan’s strategy away from a focus only on coercive actions and a one-item agenda with the Taliban involving the TTP. But there is an important caveat to this. Pakistani authorities have also signalled to Kabul that any major attack from Afghan soil will invite a Pakistani reprisal and likely hot pursuit. Casualties will not be tolerated and Pakistan’s hand will be forced to take kinetic action.

This carrot-and-stick policy will likely shape the planned reset of ties with Afghanistan. Islamabad hopes the combined effect of diplomatic engagement and trade inducements as well as pressure on the TTP issue would encourage Taliban authorities to respond to Pakistan’s security concerns.

Pakistan therefore seems intent on employing both incentives and disincentives in a renewed bid to prevail on the Taliban. It should also consider crafting a regional strategy in collaboration with China and Afghanistan’s other neighbours to mount collective pressure on Kabul to change course on the terrorism issue, which remains a common worry for the entire region.

COURTESY DAWN