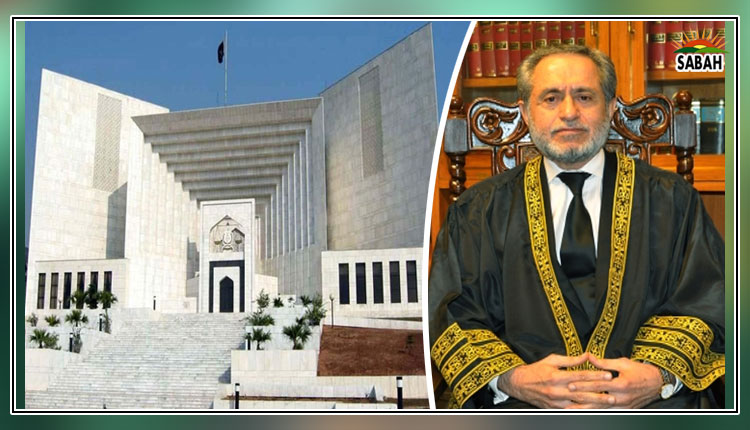

Constitutional amendments…Parvez Hassan

IT is not a clich but constitutions are, in fact, the glue that normally hold a country and its peoples bounded to oneness. As such a life-giving source to statehood, constitutions are and should be venerated as a solemn social contract overarching the existence of the state, its institutions and the people. However, not being divine or holy scriptures, constitutions ordinarily provide a mechanism for amendments to incorporate new and unanticipated events or to correct course based on experience and usage.

Pakistan recently witnessed an attempt by the coalition government to pass a constitutional package which it wanted to introduce for approval in the National Assembly and the Senate on one fateful Sunday without any prior notice of the proposed amendments to the members of the NA or the Senate. Had it succeeded in the numbers game that Sunday, the Constitution, adopted in 1973, with the informed consent of all the provinces through a protracted process of deliberations and debate, would have been transformed, some would say mutilated or disfigured, by the far-reaching changes of its basic structure, by the constitutional package. All without notice, without disclosure of the constitutional package and all without the informed participation of the people of Pakistan and their representatives in the NA and the Senate. Could there be a greater or more grotesque tragedy for the people of Pakistan and for the country?

This may be a good opportunity to reflect on some guidelines for constitutional amendments. The first is legitimacy. The present NA and the Senate have flowed from the elections in Pakistan in 2024. That they were manipulated and rigged particularly against the PTI is not credibly contested. The post-election decisions and role of the establishment have substantiated the flawed process through which a minority has been imposed to rule a majority. Irrespective of the claims of the coalition government, it is undeniable that there are serious questions about the legitimacy of the government and, absent the moral force of acceptability in the public, the coalition government totally lacks the competence to engage in the process of amending the Constitution.

The second guideline is bona fides. Here, it is well known that the trigger for the whole effort for the constitutional package was the decision of the Supreme Court on the reserved seats in the national and provincial assemblies and the earlier bold stance of the six judges of the Islamabad High Court alleging interference/dictation by the security establishment. It has been widely alleged that the real objective of the constitutional package was to neutralise or safeguard against an upcoming hostile leadership of the Supreme Court. And, the perception of a person-specific constitutional package gained so much traction that it handicapped the ability in the numbers game before the government.

This may be a good opportunity to reflect on some guidelines for constitutional amendments.

The third guideline is that the proposed amendments do not erode the basic structure of the Constitution. The 1973 Constitution and the earlier constitutional dispensations in the 77-year history of Pakistan have established the Islamic character of our state, the separation of powers, the trichotomy of powers, the independence of the judiciary, rule of law and the justiciability of fundamental human rights as included in the durable framework for our national existence. These cannot be amended, directly or indirectly.

The need-assessment is the next, fourth, guideline for seeking constitutional amendments. A mature approach in the field is minimalism and proportionalism, that is achieve objectives, first through alternative effective mechanisms, if possible, and with the least violence to the existing text of the Constitution if such an intervention is unavoidable. It is also recommended to have measured responses avoiding overkill. An example could be first try strengthening the use of constitutional benches in the Supreme Court already enabled by the Constitution instead of the surgical solution of the establishment of the constitutional court which will vitiate the basic structure of the Constitution.

Fifth, each proposed amendment should be supported by fact-based data. Thus, it will be useful to segregate the number of pending cases in the civil courts, the high courts and the Supreme Court and to determine the different delay factors in each category. This analysis might reveal that remedial measures at each level may improve the efficiency of the Supreme Court, all without the need of amendments in the Constitution for this purpose.

The sixth guideline: whatever the resultant reform agenda based on a holistic approach including the above factors must be supported by a robust process anchored in transparency, full and time-bound disclosure, adequate notice, and facilitating right to information and inclusive participation of the provinces, bar associations, CSOs and professional bodies. It would be helpful to evolve a mechanism for the review of comments and suggestions in this open national conversation.

The seventh stage, built on the edifice of the preceding six factors, would be open and free debates in the NA and Senate in full view of our national news, print and electronic media, to the requirement of a two-thirds majority in both Houses. The Constitution requires the approval of two-thirds membership of each of the NA and the Senate for passing the package and it would be a travesty of justice if such approvals are sought without a full disclosure of the amendments and providing adequate time for their consideration and discussion. International practices have moved from consent to prior informed consent as a condition to each approval.

It is shameful to highlight the eighth condition of the constitutional amendments: the voting and its counting must be in accordance with law and the decisions of the superior courts, totally free from the coercive apparatus of the establishment that has become, increasingly, a regular feature of our political governance.

A verdict for the adoption of the amendments will be legally and, morally, acceptable only if it is law-compliant, free and fair and abides by the common-sensical guidelines suggested in this piece. Such a course would avoid the arbitrariness, ugliness and disgrace of the recent Sunday night fiasco.

The writer is a senior advocate of the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

Published in Dawn, September 28th, 2024

Courtesy Dawn