CJP Qazi Fazi Isa says Parliament should not be ‘crippled’ when it was doing good because it did not have a two-third majority

ISLAMABAD, Oct 09 (SABAH): Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Justice Qazi Faez Isa on Monday remarked that Parliament should not be hampered from doing good just because it lacked the two-thirds majority required for passing a constitutional amendment. Justice Qazi Faez Isa observed that parliament passed the Supreme Court (Practice and Procedure) Act 2023 with “good intent”.

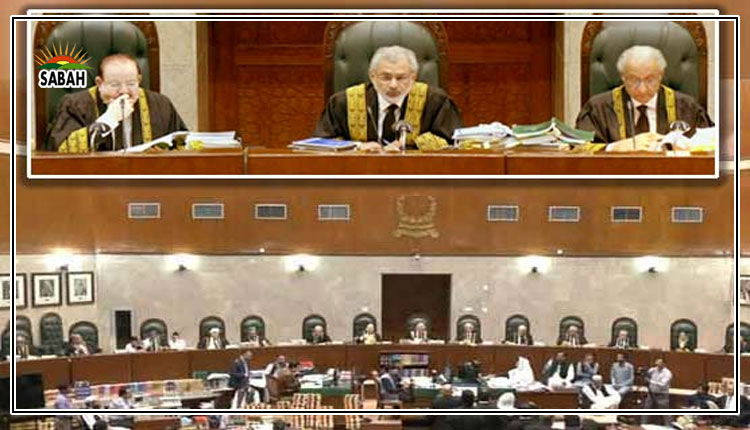

Justice Qazi Faez Isa made the remarks as a full court resumed hearing a set of petitions challenging the Supreme Court (Practice and Procedure) Act 2023 — which requires the formation of benches on constitutional matters of public importance by a committee of three senior judges of the court. The hearing, which began at 9:35 AM, was streamed live on television.

Headed by CJP Isa the bench consists Justice Sardar Tariq Masood, Justice Ijazul Ahsan, Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, Justice Munib Akhtar, Justice Yahya Afridi, Justice Aminuddin Khan, Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi, Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhel, Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar, Justice Ayesha A. Malik, Justice Athar Minallah, Justice Syed Hasan Azhar Rizvi, Justice Shahid Waheed and Justice Musarrat Hilali.

In a pre-emptive move, the Supreme Court — then led by former CJP Umar Ata Bandial — in April had barred the government from implementing the bill seeking to curtail the chief justice of Pakistan’s powers once it became a law.

At the previous hearing, CJP Isa had questioned the many legal challenges to parliament’s legislative authority, saying there had been much nit-picking over laws enacted by assemblies, but in the face of martial laws imposed in the country, there was always a complete surrender.

“We pick errors whenever parliament made a law, but surrender ourselves completely when martial laws were imposed in the country,” Justice Isa had said.

“This Courtroom No.1 carries pictures (of former CJPs) who obviated their oaths by validating martial laws, but nobody moves petitions to express opposition [to their action], except when parliament enacts laws,” Justice Isa quipped during a televised hearing. Justice Isa had intended to wrap up the case the same day, but it was adjourned till today due to time constraints.

Resuming the hearing, Justice Isa said on Monday was the last day of the hearing. The court heard arguments from a number of counsels, including Supreme Court Bar Association President Abid Shahid Zuberi and PML-N lawyer Barrister Salahuddin Ahmed.

However, a little before 6:00 PM, the CJP adjourned the hearing till 11:30 AM today (Tuesday).

At the outset of the hearing, SCBA President Abid Zuberi said that Article 175(2) and Article 191 had been quoted in the Act. He read out Article 191 which states: “Subject to the Constitution and law, the Supreme Court may make rules regulating the practice and procedure of the Court”.

The lawyer contended that the “only authority that can make rules regulating the practice and procedure of the court is the honourable SC and not Parliament”.

He said that “subject to the law and the Constitution” did not mean that Parliament could legislate in this regard. “If rule-making power is made subject to legislation, then the rule-making power of the SC will become functus officio,” he said.

He further contended that constitutional grant of rule-making power was construed as a continuing power, “so there cannot be any limitations on that”.

However, CJP Isa stated that under the counsel’s arguments six words of the Constitution could be deleted “as rendered meaningless”. “I am reading it like that if I accept your contentions,” Justice Isa said.

Abid Zuberi contended that “subject to” meant that it was restrictive in nature because a constitutional power, which was a continuing power, was being given to the SC.

The lawyer said that if the Constitution was giving the legislature power for rule-making, it used specific words. He referred to Article 154(5), which states: “Until Majlis-i-Shoora makes provision by law, the Council [of Common Interest] may make its rules of procedure”. He also referred to Article 6(3) and Article 151(2).

Justice Akhtar asked whether subsequent legislation could “displace” rules that were lawfully and constitutionally framed by the apex court.

“No, they cannot for the simple reason that it will become ad nauseam. For example, can now the SC make a law regulating its practice and procedure overriding Parliament’s? Where will we stop?” Zuberi contended.

At one point, CJP Isa remarked, “The day we hear this case, the weeks we hear this case, our institution exceeds our disposal. The day we don’t, our disposal exceeds our execution. If you think this is a never-ending hearing, this is the last day of the hearing.”

He urged the SCBA president to continue his arguments in the case, telling him to move on to the next point. He expressed displeasure with Zuberi submitting documents to the court during the hearing.

“This is most unfair. We had asked people to file […] We have told everybody to file […] And is this an easy thing to read? Could you not have done this before?” he asked Zuberi.

Moving on with his arguments, the SCBA president said that Article 175 gave Parliament the power to legislate but it also had to be read with Article 142(A) and Entry 55.

“Does Article 191 confer jurisdiction or does it confer power?” asked Justice Ahsan.

“I would say it confers power,” Zuberi said. He said that the most important word used in the provision was “regulate”.

“Article 191 is not a jurisdiction conferring article it is a power conferring article. And there is a distinction between jurisdiction and power,” Justice Ahsan remarked.

Continuing his arguments, the counsel said that the power exercised under Article 191 was a constitutional power which vested the SC to regulate its practice and procedure, adding that Parliament could not interfere in this regard.

He said that the words “subject to” meant that it was not an enabling provision but rather a restrictive provision.

“If you argue in context of Pakistan and why presumably the legislature enacted this law […] they are giving a right of appeal under Article 184(3). You [have not talked] about how Article 184 has been used. Either say it is being used correctly or incorrectly or sometimes being used correctly and sometimes incorrectly. Say something,” Justice Isa told the lawyer.

He said that the SCBA president had not brought a petition before the court and asked what his “anxiety” was with regards to the law. CJP Isa then asked about how Article 184(3) had been used.

“Human rights cell, is it mentioned in any rule or law? Put Parliament aside. Is there any mention in our own rules?” CJP Isa said. He went on to say that Article 184(3) as far as habeas corpus was concerned, there was mention of it in the rules.

“But the other powers used under Article184(3) were those mentioned in the rules or not?” he asked. Justice Isa said that Article 191 did not state that the chief justice could make the rules or a “human rights cell”.

“Before the world raises a finger, I raise a finger on myself. Powers used under Article 184(3) in thousands of cases — some were of general public interest [but] some became personal — you are not explaining this,” CJP Isa said.

He said that how Article 184(3) had been used was a “reality of Pakistan”. He told the lawyer to either argue that it had been used correctly or to say it was not and then give a remedy.

“If a mistake has been made, then whose responsibility is it to find a remedy? The biggest responsibility is of this court. After that maybe Parliament. If we have made a mistake then we should rectify it. If Parliament has made a mistake then it should rectify it. If we don’t correct our mistake, then can Parliament?” Justice Isa said, remarking the counsel was overlooking whatever had happened in Pakistan.

CJP Isa remarked that the SCBA president was representing a particular party (PTI), to which Zuberi said he was not. The lawyer stated that he was appearing on behalf of the bar association.

“So tell us the stance of the SCBA. The way in which Article 184(3) being used, was it correct? […] If we strike down this law, so will it be correct if I keep using [Article 184(3)] in the same way as before?” Justice Isa asked.

Zuberi said that Article 184(3) was used incorrectly in the past and several questions had been raised about it. He said whether it was used incorrectly or incorrectly, it had to be examined who had the competence or jurisdiction to rectify it.

Justice Minallah asked whether Parliament, which had the jurisdiction to enlarge and supplement the SC’s powers, was “bereft of jurisdiction” if fundamental rights were being violated.

Justice Ahsan observed that he had stated during the first hearing, that the matter at hand did not concern whether it was a ‘good or bad’ law. “It is a question of competence,” he said.

Zuberi said that the court had to see whether Parliament had the competence to make the Act. He said that if the court was violating any rules or the Constitution, then the case should be brought be challenged before the SC.

“The chief justice exercised his powers under this law by fixing these petitions. Why not more important petitions such as enforced disappearances, other human rights issues? That is a question Parliament wanted to address. Why should these cases have been taken first why not other more important cases?” Justice Minallah asked.

Zuberi said that the power to regulate practice and procedure vested with the apex court and not Parliament. He said that a law could be challenged on two grounds: if it violated fundamental rights or if it violated a constitutional provision.

Coming to CJP Isa’s remarks, Zuberi said that there should be a right of appeal under Article 184(3) but it needed to be given through a constitutional amendment. When Justice Isa asked about the SCBA president’s opinion on the use of the article, the latter said that it had been used both correctly and incorrectly.

The lawyer said that the passage of the law had an effect on the doctrine of separation of power. He said that Article 184 was the original power of the court, Article 185 was appellate power, Article 186 was advisory power and Article 188 was review power.

He said that appeal was only provided under Article 185. “If you want to give an appeal then you have to amend the Constitution,” he said.

“If somebody, albeit not even fully authorised, is doing something to help the nation, the SC, you should say strike down because they’re not following some perceived letter of the Constitution? That will be a stretch,” Justice Isa said.

Zuberi insisted that a right of appeal should be provided but reiterated that the method of doing so was not correct.

However, CJP Isa noted that some of the counsels while making arguments had attacked Parliament’s intent while legislating. “I am saying the intent of Parliament is good […] they said it is a person specific law. Tell us how it is person specific,” Justice Isa said.

“If we open the door for Parliament to interfere in every matter the SC may or may not take up, then there is no end to it. There would be good legislation and there would be bad legislation. How do you differentiate? The differentiation is put in the Constitution by the framers,” Justice Ahsan said.

CJP Isa said that the only difference between a law and a constitutional amendment was a numbers game. “It is the same persons doing the law-making, the same parliamentarians who are making the law,” Justice Isa said.

He said that Parliament should not be “crippled” when it was doing good because it did not have a two-third majority. The SCBA president then concluded his arguments.

Petitioner Umar Sadiq’s counsel Dr. Adnan Khan then took the rostrum. He said that framers of the Constitution had conferred the legislative power on Parliament for review but not for practice and procedure. He said that practice and procedure was the court’s internal matter.

He further argued that the office of the chief justice “had been done away with” by the law. “It has been abolished for all practical purposes,” he said. Khan said that the institution of the SC stood on two limbs, the chief justice and its judges, under Article 176.

He said that the chief justice was senior among equals. “What makes him senior among equals is administration,” Khan said.

In his arguments, petitioner Advocate Muhammad Shahid Rana said that the power to constitute benches had been given to the chief justice by the SC. “If chief justice wants to curtail this power, then it would be better to go to the SC, sit in the committee and have a decision made,” he said.

During the hearing, Justice Isa asked Attorney General for Pakistan (AGP) Barrister Mansoor Usman Awan whether he would lead the arguments or respond to those made.

At the same time, lawyer Imtiaz Rashid Siddiqui came to the rostrum and asked to present his arguments. However, Justice Isa noted that he had done so during the previous hearing and asked him “not to interrupt”.

“This is very unfair. You said that let the AGP argue, we will hear you later,” the lawyer said. CJP Isa then asked to be shown the order.

“This is very unfair. I will not argue if you don’t want to hear me but don’t put things which are factually incorrect,” Siddiqui said, to which CJP Isa wondered if there was any harm in being civil.

“Look at your conduct and then talk about us. Your conduct is not right. That is why Khawaja Tariq Raheem refused to come today,” Siddiqui said. CJP Isa then told the lawyer to not argue for those who were not present.

“He is my colleague. He has instructed me to inform you of this,” Siddiqui said. Justice Isa then read out the order, which said that the lawyer did not wish to submit anything further and his written submissions could be read.

“Thank you very much, please take your seat,” CJP Isa said. When the lawyer protested, Justice Isa said, “Please take your seat before I issue something.”

PMLQ counsel Zahid Fakhruddin Ibrahim said that repeated questions had been raised but no one had identified which fundamental right affected the petitioners and how the independence of the judiciary was diluted by the law.

He said that while it could be argued that once the door is opened for Parliament to legislate even on the practice and procedure of the SC, tomorrow it could make another law.

“But when it makes another law, it will be tested whether they are interfering in the independence of the judiciary. And it will be struck down if they do so. But not at present, this law does not,” he said.

Justice Ahsan questioned how the lawyer could say that when the law obligates the chief justice and two other judges to act in a certain manner.

“As what rightly pointed out by one of the counsels, they are micromanaging or trying to micromanage or trying to interfere in the independence of the judiciary in so far as Parliament will now dictate how benches are to be formed or what cases are to be fixed […]. If this is not interference in the independence of the judiciary and micromanagement of the judiciary, I don’t know what else would be,” Justice Ahsan said.

Ibrahim said that these matters could not be looked at in isolation. “Let’s face it. I do not know how how cases get fixed. I do not know how benches get constituted. I do not know how 184(3) case get presented on April 12 and gets fixed on April 13. This itself is vindication of this law,” he contended.

Justice Minallah said the current proceedings were a “classic example” of how powers were exercised by the chief justice. “As I pointed out earlier, there are a lot more important cases which never get a turn,” he said. He said that Parliament had only tried to structure the discretion which this court was refusing to do, adding that there were “obvious abuses”.

Justice Akhtar said that the committee that would decide the benches under the law would not be the master of the roster because “it was a creature of Parliament’s will”.

“Parliament has willed it into existence. Therefore, it is Parliament which is the master of the roster,” he remarked,

CJP Isa said that the SC ruled simply stipulated that the chief justice would constitute benches. He said that a practice had “developed” that every week a list of cases would go to the chief justice about which case would go to which judge.

“I have discontinued that practice. This is not even the job of the chief justice. This is the job of the registrar,” he said.

After Ibrahim wrapped his arguments, Barrister Salahuddin Ahmed, representing the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), came to the rostrum. At the outset of his arguments, the lawyer said that the case “primarily related to internal threats to the independence of the judiciary”.

“My submission will be that the constitutional guarantee of independence of judiciary covers both external and internal independence,” he said.

Barrister Ahmed argued that the concerns about the “untrammelled powers” of the chief justice were not new and had been raised multiple times, even by the judiciary.

“Ten members of this present bench have raised concerns about the concentration of powers in the office of CJP and my submission would be that that in itself disposes of any argument,” he said.

During his arguments, Barrister Salahuddin recalled several resolutions passed by Parliament in the past, which demanded regulating the suo motu and master of roster powers.

“Eventually, there has been a change in the tone and direction [of resolutions] in the last two to three years. In the most recent resolutions, Parliament has been asked to directly act under Articles 175 and 191 and presumably the change in direction was because there was no effective response from this court on its administrative side,” he highlighted.

He further contended that the power to make benches and assign cases was “not a constitutional power” neither was it mentioned in the Constitution.

However, Justice Akhtar said here that the “CJP as the master of the roster” was a power that went back to the beginning of British rule and the provision continued for several years.

“If you look at it in historical perspective, there is this constitutional rule of ancient standing,” Justice Akhtar said.

“The question to you is this: In our constitutional law, conventions are legally enforceable. So even if this rule is now embedded in case law, can it not be said that it is a constitutional convention and therefore Sections 3 and 4 [of the law] are ultra vires?” he asked.

For his part, the PML-N lawyer said constitutional conventions were subordinate to constitutional intent.

He then proceeded to give an example from the Indian SC, however, CJP Isa interjected and said that Pakistan gained independence in 1947.

“We can learn from other countries by all means but while we refer to Indian judgments, I have never seen it reciprocated in India,” Justice Isa said. “I am just seeing this perpetual fascination with what happens across the border. Why can’t we just stick to our Constitution?” he asked.

“Let us be guided by our own light,” he added. For his part, the PML-N lawyer said one should learn from the mistakes of the neighbouring jurisdictions.

At one point during the hearing, Justice Waheed asked if Parliament had intervened to remove the errors in neighbouring in countries. “Or are there examples in the world that legislation has been done regarding practice and procedure?” he questioned.

Barrister Salahuddin gave the example of the United Kingdom. However, CJP Isa said: “The American SC doesn’t have the concept of a bench […] and the UK is the same situation.”

Parliament’s competence

Meanwhile, Justice Ahsan asked if the “legislature can turn around and say the interpretation of a constitutional provision done by the SC was incorrect and we correct it”. To this, Barrister Salahuddin replied in the negative.

During the hearing, Justice Minallah told the PML-N lawyer to explain if Parliament was competent to legislate. “If it is competent, then let us respect the Parliament and not view this as a dictation.

“It is a law then competently made. But first, let us know if Parliament is competent to legislate,” Justice Minallah added.

At the same time, Justice Isa said that one scenario was to let the law function, in which case there could be dissatisfaction with its functionality.

“That question, we are assuming that we are not capable of manning the ship. The only thing is that previously there was a pilot and now there are two co-pilots,” he said and gave an example of an acting CJP coming in when the incumbent left the country.

“Why are we scared of our own shadows? The co-pilots […] why are we all assuming that we are leading to the iceberg that lies underneath? Nothing has happened so far,” he remarked. The CJP added that the real question was about competency.

Barrister Salahuddin said Article 191 was a standalone “enabling provision”. “Read with the first part of Article 58, it is more than enough to confer legislative competence on part of Parliament,” he said, adding that matters of SC relate to the federation.

At that, the CJP asked if the high courts were better run than the SC.

For his part, the lawyer said it varied from court to court and chief justice to chief justice. “And that is precisely the rationale of this law, that it should not depend on the chief justice and there should be some kind of framework and structure,” he contended.

Here, Justice Isa pointed out that there was a forum of appeal in the high courts. “Here, the problem has culminated with a number of factors — accumulation of power, random exercise of power, non-transparent manner of operating of power, excessive use of 184(3) … a combination of these factors has resulted in the making of this act,” he said.

Meanwhile, Justice Akhtar said that the solution was to give the power to the full court “which is where, presumably, it always lies when the court makes its own practice and procedure”.

Justice Akhtar also went on to say that he had “serious reservations” with things being imputed to retired chief justices. “We should not impute things to those who cannot defend themselves, sitting in open courts,” he asserted.

The judge also asked: “If this law is validly enacted, who is the master of the roster? The creation of Parliament — whether it be a committee of one, two, four or ten — or Parliament? And if Parliament is the master of the roster for the practice and procedure of SC, then where does that leave separation of powers? Where does that leave independence of judiciary?”

Barrister Salahuddin said that legislation by Parliament in this case was meant to promote access to justice.

At one point during the hearing, Justice Minallah said every law needed to be seen in the historical context. “Master of the roster and the powers exercised probably were viewed by the representatives of the people … so that is why there was a need for the law and we cannot ignore or turn a blind eye to the historical context why it was so necessary,” he said.

Justice Shah concurred, saying that the Parliament was being referred to in a derogatory manner “as if they are the Indians”.

“The Parliament is a house that represents the people of Pakistan, so the people of Pakistan through their representatives cannot have the right to say how the SC has to function … we are trustees doing work for the people of Pakistan … so even if the word dictation was used, people can tell us what to do,” he said.

However, Justice Ahsan contended that the 34 MNAs sitting in the Parliament “don’t speak for the people, they speak for a party for the reason that the majority is the government actually”.

“If the people of Pakistan have to have their will, yes, it is their country, they have given the Constitution, they have a right and power to amend the Constitution,” he added.

For his part, the PML-N lawyer said the spheres of legislative competence and infringement of judicial independence were separate issues, adding that if the Parliament was legislatively competent to bring in new SC rules, they would be checked by the judges.

“And if there’s anything in those rules that effectively impairs your independence, then you will be free to strike it down,” he explained, adding that if the “opening of the door was misused” the SC could step in.

Meanwhile, CJP Isa said the law in question did not stipulate anywhere the consequences of strictly abiding by it, adding that the law had hence left room for the SC.

“Nobody has touched upon this point at all. Everybody is assuming that it is extremely mandatory with grave consequences if not abided.

“So if we take that sort of a middle ground and say it is not mandatory to that extent, but it is a law,” the chief justice said, asking Barrister Salahuddin to touch on that.

The PML-N lawyer said that when the law was in the field, the judges were expected to abide by it.