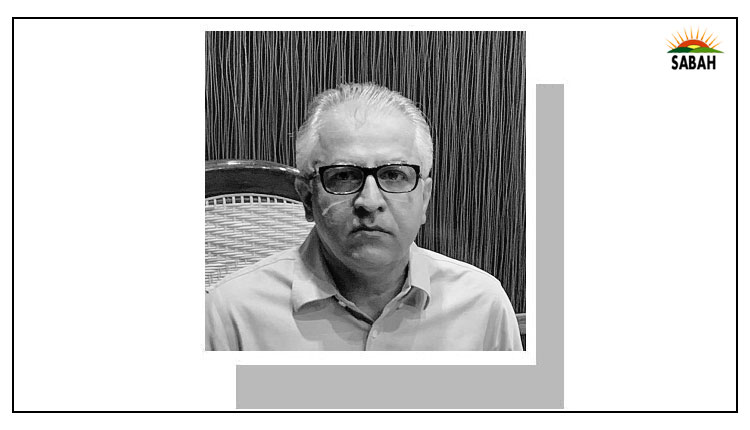

Budget 2024 & food security…Aijaz A. Nizamani

PAKISTANS budget proposal for 2023-24 is being debated in the National Assembly and is expected to be approved. As usual, the budget, with an outlay of Rs14.6 trillion, relies heavily on borrowing and involves debt repayment of Rs7.3tr from a tax collection target of Rs9.2tr. What is our asset base against a high national debt of nearly Rs60tr? Sadly, we have hardly anything to show against this mountain of debt.

The war in Ukraine and global inflation have shown how important it is to have national food security. What does the budget have for food security in the short and long run? Unfortunately, it is business as usual, with a band-aid approach to a crumbling infrastructure, worsened by climate change, as seen in the case of the rains last year in Sindh and KP.

Though agriculture is a provincial subject, food security has a national mandate, as seen in the plethora of agriculture research institutions at the federal level. The budget has assigned an agri credit target of Rs2,250 billion to the banks. It has allocated Rs30bn for converting 50,000 electricity-/ diesel-run tube wells to solar. It has also provided some tax exemptions for seed import. Notably, in last years budget, this target had been set at Rs1,850bn. Invariably, all governments put a premium on agriculture in the budget document (which is not the case for industry), and that is a welcome gesture.

However, one must also be critical. Economic output contracted in 2022-23 and credit disbursement to the private sector fell by 98pc, with the new disbursement being as low as Rs28bn. This involves the entire private sector, including manufacturing and services. Compared to that, banks were reporting almost full achievement of the agri credit target of Rs1,850bn and the government was comfortable enough to set the target of Rs2,250bn for the year 2023-24!

Finance is to business as air is to lungs; our policymakers must realise the importance of commercial and competitive sources of finance for agriculture, which has great significance for our national food security. First, they have to accept that the current formal (largely the banking sector) mechanism of financing is not working and has to be thought afresh. The finance minister while discussing financial matters with SMEs (this would include rural food processors) announced that the government was taking a hit of 20pc credit loss in order to facilitate bank finance for SMEs. One former finance minister said that it was not in the banks DNA to extend credit to companies in Pakistan. The government and central bank have to think beyond banks to extend private-sector financing to businesses, including agriculture, in Pakistan.

Peer-to-peer lending is an option but government regulations in the form of SRO436 (2022) is a hopeless policy, according to which an individual cannot borrow more than Rs1 million in a peer-to-peer lending arrangement and has to be funded by at least two individuals. This means an individual cannot lend more than Rs500,000, thus defeating the purpose. Hundreds of millions are invested by a single arthi or private moneylender to farmers. Reflective of this, policy options should have opened up more avenues of financing and increased competition, resulting in reduced cost of capital for farmers. Regrettably, our farmers are completely unaware of policy tools devised by babus who have no idea how the real market operates.

The credit interest rate support for 50,000 tube wells conversion to solar would certainly help farmers but the benefit would largely be confined to Punjab. Eighty per cent of the groundwater in the province is fresh. Compared to that, Sindh has far too few tube wells as 80pc of its groundwater is saline. This budgetary support also rests on the false assumption that groundwater is inexhaustible, and that making it cheaper to extract would have no implications for future availability.

Agriculture in this country needs private-sector investment for its canal and drainage infrastructure in an age of frightening climate change. It would have been far more effective had the central food security ministry, in consultation with the provincial departments of agriculture, irrigation and forests, come up with a hybrid approach to water conservation investments which would have resulted in making several Tarbela dam-level water quantities available for early Kharif and Rabi crop.

Canals are government structures and as per the Provincial Irrigation Drainage Authorities Act of 1997 can and should be handed over to farmer organisations. In an era when 80pc of tax collection is used for debt-servicing, the government has to think of bringing in farmers and the private sector to invest in canals. The books show there is simply no other way.

Similarly, watercourses, which are the last leg of the irrigation system and that actually bring irrigation water to the farms, are community structures. They usually serve 15 to 30 farmers with a command area of 300 to 500 acres. It would have been far more effective if Sindh had the option of interest-rate assistance for watercourse lining funded by banks, as is the case in individual tube well conversions to solar. So despite the enhanced numbers for agriculture in the budget for 2023-24 we cannot expect any transformation of the farm sector in the foreseeable future.

The most important lesson that policymakers must learn is that farm commodity prices should not be suppressed, which is invariably the case for all produce that comes from the farms. Such price suppression has far more severe implications for rural producers. Better means can be found to support both the rural and urban poor to secure food through government food stamps, rather than suppressing farm commodity produce prices.

We all saw in the recent boat tragedy near Greece what happens when poor youth in the rural areas are pushed to the margins. The rural sector does not require any favours; all it demands is a level-playing field with functional infrastructure and competitive sources of finance.

Courtesy Dawn