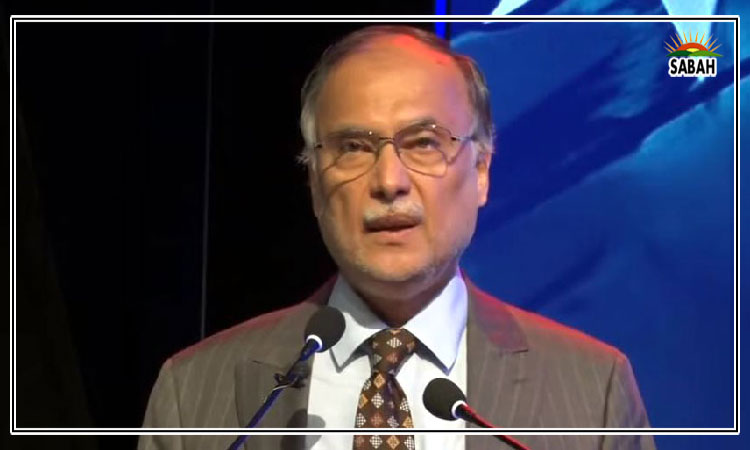

American versus Chinese aid…Syed Mohammad Ali

American policymakers have repeatedly criticised increasing Chinese aid to poorer countries for lacking transparency, for being delivered in a top-down manner, and even for becoming a predatory tool that compels indebted countries to fulfill Chinas geostrategic objectives. However, American policymakers must take a much closer look at how their own aid disbursement mechanism works, which are also by no means ideal.

The US itself primarily provides bilateral grants instead of disbursing aid in the form of loans, but it does exert significant influence over the World Bank and the IMF, which provide poor countries aid in the form of loans. Much has been written about problems with the conditionalities linked to the provision of World Bank and IMF loans, which primarily rely on lopsided market mechanisms that seem unable to ensure equitable growth. Conversely, even American bilateral grants that are meant to promote altruistic goals often produce lackluster results, which is a problem of significant consequence as the US is the largest bilateral donor in the word.

Americas agency for international development, USAID, aims to not only exert American soft power to achieve strategic goals but also to liberalise struggling economies to enable its own multinationals to outsource production using their cheap labour, and to pry open rural areas in these poorer countries to American agribusiness interests.

Despite all the rhetoric about participatory development, the aid industry continues to ignore or sideline local expertise. US bilateral aid is particularly dependent on western contractors which, in turn, rely on a pool of highly paid consultants who move from country to country providing expert advice aiming to boost growth, improve governance or make social service delivery more effective.

USAID has also become beholden to private sector contractors in the same manner that the defense industry has developed close ties with the military and with American policymakers. USAID administrator Samantha Power herself has acknowledged the growth of an aid-industrial complex in America, whereby American aid has become intrinsically linked to specialised for-profit entities which owe their existence to the delivery of American aid to poorer countries.

USAID aspires to empower poorer countries by building local capacities to help achieve sustainable development. Yet, according to a database maintained by DevelopmentAid, around 85% of USAID is funneled through US-based contractors.

USAID began to increasingly rely on the private sector in the 1980s due to Reganomics compulsion to trim publicly funded offices, including USAID. Thus more official US aid began being disbursed through consulting firms, and these firms grew in terms of their scope of operations. Development consultancies often rely on top-down models of development that are readily implementable in different countries based on the rationale of replicating best practices. Yet, these so-called best practices rarely produce consistent results given the obvious variance in ground realities around the world.

USAID has been criticised for not spending enough time interacting with local stakeholders and for becoming increasingly reliant on consultancy firms and their hierarchical chain of subcontractors. While the salaries of senior development executives amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars per annum, local development practitioners get a meager fraction of the overall administrative budget of USAID projects. Local subcontractors also have little say over how projects are developed or implemented. As a result, aid delivery is often wasteful, irresponsive, and lacks adequate participation of local stakeholders.

In the bid to make US aid less top-heavy, the head of USAID recently pledged that the agency would try to direct a quarter of its funding to local partners by the end of the 2025 fiscal year. Whether restrictive USAID funding requirements will be sufficiently modified to secure this goal remains to be seen. USAID will simultaneously need to give local stakeholders a much greater voice in designing development efforts if American aid delivery is to become meaningfully distinct from the prevailing Chinese aid model.

Courtesy The Express Tribune