A struggle for sanity…Ghazi Salahuddin

Chancing upon a history quiz on YouTube, I was a bit intrigued by a question on Winston Churchill. Though I vaguely had some idea about what it was about, I was a bit taken aback by how it was put.

Well, the question was: Winston Churchill is one of the most legendary and greatest known leaders of the 20th century. However, he suffered from depression. What was the term he gave to his depression? And the options were: The black dog / The rough reptile / The sad clown / The surly serpent.

Interesting, isnt it? Anyhow, the answer is the black dog, which may be appropriate for an imposing personality of Churchills looks and character. Now, as I paused to savour this information, I realized that the day Tuesday was coincidentally being observed as World Mental Health Day. Some events were held in Pakistan to underline the importance of spreading awareness about the mental well-being of the people.

As for Churchill, one point to highlight beyond the quiz is that he had sought medical advice to deal with his depression, which was really severe at times. There have been suggestions that he either suffered from bipolar disorder or manic depression.

People in Pakistan, particularly those who are well-known in society, would hesitate to consult the relevant physician if they suffer from any mental health problem. There is a stigma about it, making this crisis more problematic. In fact, the situation is quite frightening. In addition to lack of awareness, there is a severe shortage of the necessary health facilities and dearth of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists.

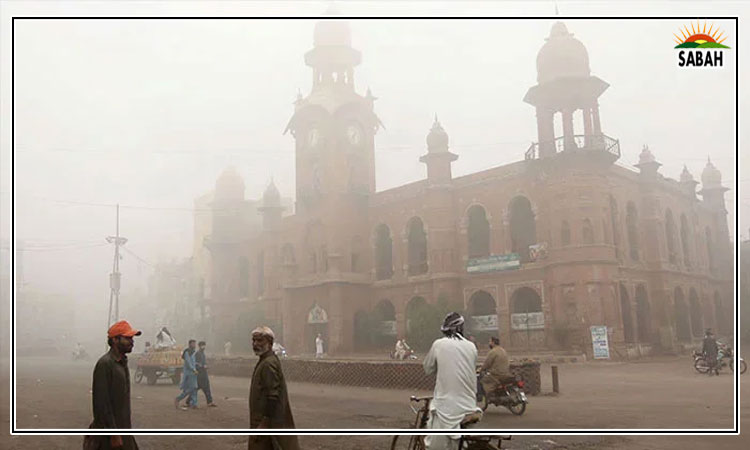

Hence, I will not go into any details about the mental health and social well-being of the ordinary citizens of Pakistan. The picture is so scary that even looking at it would greatly enhance our collective depression of the kind that has seemingly become incurable.

But I would like to mention, in passing, the dedicated efforts of the Pakistan Association of Mental Health in raising awareness of this nationally debilitating disorder. This association was founded by distinguished psychiatrist Dr S Haroon Ahmed, who said some years ago that at least two million persons in Karachi suffer from mental, emotional, intellectual or social adjustment disorders. This would appear to be an understatement if you carefully follow reports of crime and deviant behaviour in the city on a daily basis.

According to a survey conducted some years ago (and the situation must have worsened now) every fourth house in Karachi had a psychosomatic or psychiatric problem. Every second house had one or more persons taking tranquilizers.

In a larger perspective, the WHO has said that 10-16 per cent of the general population in Pakistan suffers from mild to moderate psychiatric illness. In addition, one per cent of the population suffers from severe mental illness. As many as 24 million people are in need of psychiatric assistance.

We often talk about the emotional benefits of a supportive family system. Experts agree that this is a positive dimension of our culture. But the family cannot be a strong defence against anxiety and depression in an impoverished society where the poverty levels are rising. In many ways, society is also changing, and it is not oblivious to global trends of depression and loneliness, thanks partly to how digital technology is impacting our lives.

There is a lot that one could say about the disdain with which the policymakers of this country look at the emotional and psychological problems of mainly the vast number of our young people. Even in the educated middle-class, more and more young people are seen to be drifting into pathological depression. One measure of what is happening to the young is that almost all of them are desperate to go abroad. Take this as evidence of their loss of hope in the future of this country.

I have a number of stories of what the young feel and think about their present state of affairs, through personal encounters and after sharing thoughts with friends who have to deal with difficult and disturbed children. Just one example. A mother who is very close to her children reported how her son who has just stepped out of his teens very seriously posed this question: Why is it necessary to go on living?

Such existential feelings may be common to young people in many other countries, giving the present state of the world and the disasters that have ripped through many communities. A monumental tragedy is playing out in the Middle East and the war between Hamas and Israel has literally destroyed the peace of mind of the entire world. It is hard to imagine that so many supposedly civilized countries cannot understand the immortal longings of the Palestinians for freedom and justice.

By the way, the theme of the World Mental Health Day this year is: Mental health is a universal human right. This includes, in the words of the WHO, the right to be protected from mental health risks, the right to available, accessible, acceptable, and good quality care, and the right to liberty, independence and inclusion in community.

What do these words mean to us, in this country? The very reference to liberty, independence and inclusion in community would appear to be a fantasy. The human rights violations that our people suffer go far, far beyond the range of mental sickness. Hence, the people are not left with any strength to cope with emotional stress and anxiety and depression.

One problem is that those who wield power and authority in our society are just not concerned about the mental well-being of primarily the young. They may see it as a joke that Japan has appointed a minister for loneliness. Sweden has a minister for social affairs. There have been calls in many countries for a similar post. Britain has a minister of state for civil society. But Pakistan may prefer to just not have a civil society.

Courtesy The News