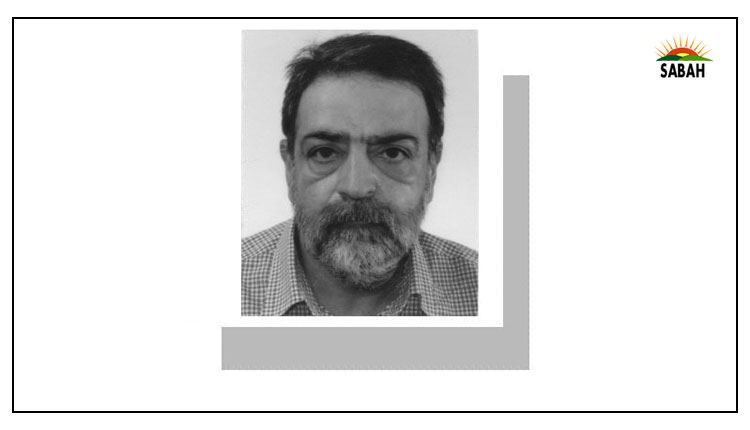

A people’s poet…Mahir Ali

WE live in a world where they say we communicate more, but the world stayed silent when slave trade was making money/ The world stayed silent when the Nazis started to kill trade unionists, people with disabilities, homosexuals, left-handed people and Jews/ And now in the age of the global village and mass communications the world is staying silent when Palestinians are being annihilated

The outstanding British poet, novelist, broadcaster, actor and agitator Benjamin Zephaniah wrote those words several years ago but, like much of his verse, they remain potently relevant. And alive. Unlike, depressingly, the poet himself, who died last week at the age of 65 just two weeks after being diagnosed with a brain tumour. To paraphrase his favourite Dylan Thomas poem, he went gently into the good night after a lifetime spent raging against the dying of the light.

When I was young, he once noted, there were two things I really wanted to see: a free South Africa and a free Palestine. That wish remained only half-fulfilled. In the former instance, his contribution was recognised by none other than Nelson Mandela. In 1982, the first single The Wailers recorded after Bob Marleys death was Free South Africa, with Zephaniah on vocals. Mandela heard it on Robben Island and, a decade later, sought out Zephaniah on his first visit to Britain, requesting him to host a 1996 concert in honour of Mandela.

There was no comparable progress on the Palestinian front. Zephaniah first visited the occupied territories in 1990, and the artistic consequence was a travelogue interspersed with poetry, Rasta Time in Palestine. Over the decades, his passion for the cause never wavered. Hardly any obituary has acknowledged that he was a patron of Britains Palestinian Solidarity Campaign.

Born in Birmingham to parents from Barbados and Jamaica, he had a difficult birth and health issues pursued him into adulthood. Severe dyslexia led him to drop out of school in his early teens, and enter a life of petty crime that in one instance involved almost being beaten to death at a police station. By his late teens, Zephaniah realised that an early death beckoned unless he escaped his milieu, so he went to London and joined a different kind of gang of poets and artists. He thrived, despite his abbreviated schooling and lack of further education. That was not unrelated to the fact that he had resolved at the age of eight to go vegan, and to earn his living as a poet. His reading woes as a dyslexic did not interfere with his determination to express himself.

He did so in ways that appealed to those who disdained poetry mainly attributed to dead white males. Most people ignore most poetry because most people ignores most people, as the late poet Adrian Mitchell put it. Zephaniah did not follow that trajectory. He spoke directly to his burgeoning audiences, with little patience for abstractions, allusions or complicated imagery. Whatever he wanted to say, he said it straight, taking no prisoners.

Early adulthood in Thatcherite Britain meant there was no dearth of domestic topics, but he never resiled from keeping a sharp eye on global affairs. He lapped up the adoration of the literary establishment and was willing to assist the British Council in disseminating the gospel of British multiculturalism, but drew the line at kowtowing to the political establishment. Being offered induction into the Order of the British Empire in 2003 was a recipe for indignation.

As he wrote in The Guardian, I woke up on the morning of November 13 wondering how the government could be overthrown and what could replace it, when he saw a letter from the prime ministers office. He went on: Me? I thought, OBE me? [ ], I thought. I get angry when I hear that word empire; it reminds me of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised Benjamin Zephaniah OBE no way Mr Blair, no way Mrs Queen. I am profoundly anti-empire.

Unlike the Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer whom Abbas Nasir eloquently eulogised in his weekend column Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah was not assassinated by an empire or its agents. He leaves behind a treasure trove of books and music or spoken word albums that will be cherished for generations to come. But his living voice with its endearing lisp and Caribbean-flavoured Brummie tones and his limitless compassion for the oppressed all across the world will be sorely missed.

Alongside a bunch of talented contemporaries and predecessors, he liberated poetry from the page and brought it to the people. I think poetry should be alive, he once said, you should be able to dance to it echoing Emma Goldmans century-old opinion: Its not my revolution if I cant dance to it.

Courtesy Dawn