A critical mass of talent …. Dr Ayesha Razzaque

In nuclear physics, under certain conditions that include shape, density, environment, etc, critical mass is the minimum amount of fissile material needed to sustain a nuclear chain reaction.

If the mass of the material is below this threshold (sub-critical), the reaction will not be self-sustaining and fizzle out. If it exceeds this threshold (super-critical), it can lead to a sustained and possibly uncontrollable nuclear reaction. For a perfect sphere of Uranium-235 that is not encased in a material that may reflect escaping neutrons back to the sphere, the critical mass has been determined as 52 kilograms.

This concept also exists in business, where a ‘critical mass of talent’ refers to the minimum number or concentration of skilled, knowledgeable, and experienced individuals required in a group, organization, or region to drive success, innovation, and growth. When this critical mass is achieved, the collective abilities of the group can lead to significant advancements, create a positive feedback loop that attracts more talent, and establish a competitive advantage.

What is the critical mass of talent in a country of 250 million souls to become the world’s leading destination for high-tech design and development, high or low-tech manufacturing and assembly, finished textile products, or just the go-to source for white cotton towels and socks?

I don’t know what the numbers are for each of these but what I do understand is that you have to master making white cotton socks and towels before you can graduate to other high-quality textiles and need to master that before you start thinking about building exportable but commonplace household appliances like TVs, refrigerators and microwave ovens. Once you are recognized for having the skill to build boring appliances, you can start dreaming about building advanced technology products that require expertise in cutting-edge manufacturing processes like, say, an iPhone.

Theoretically, 250 million are enough people to dominate art to space exploration and everything in between but let’s not be greedy. Coursera has been publishing its Global Skills Report annually (‘Pakistan and the skills report’, The News International, June 20, 2024). The latest report for 2024 categorized and ranked skill levels in three areas for 109 countries, tracking where on the globe skills are approaching critical mass to become interesting. Spoiler alert: Pakistan is classified as “lagging” in the global skill ranking.

In December 2017, Apple CEO, Tim Cook, spoke at the Fortune Global Forum in Guangzhou, China. A short clip of the public remarks he made at that event has been in circulation since then and keeps cropping up now and then. In that excerpt, he says: “There’s a confusion about China. The popular conception is that companies come to China because of low labor costs. I’m not sure what part of China they go to, but the truth is China stopped being a low-labor-cost country many years ago. And that is not the reason to come to China from a supply point of view. The reason is because of the skill, and the quantity of skill in one location and the type of skill it is.

“… The products we do, require really advanced tooling, and the precision that you have to have, the tooling and working with the materials that we do are state of the art. And the tooling skill is very deep here. In the US, you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I’m not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields.”

Cook’s comments were covered more fully in an article by Glenn Leibowitz in Inc. magazine that appeared on December 21, 2017.

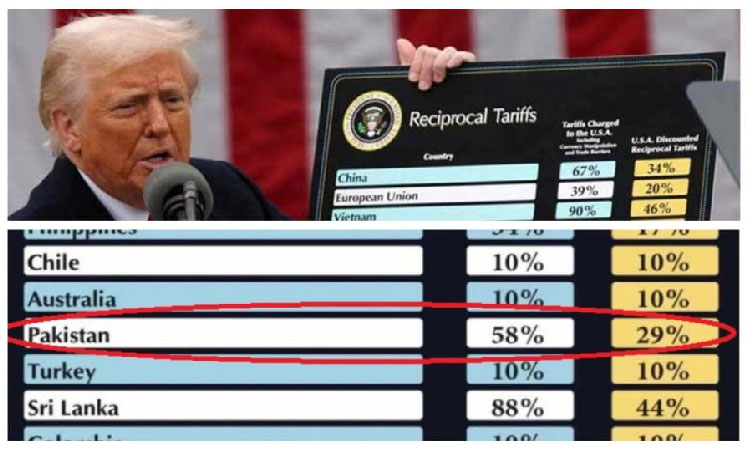

And yet, people we expect to know better continue to sell us and, more importantly, those making decisions dreams of transforming the economy of this nation shamed by a 58 per cent literacy rate and a population of 26 million children that ought to be in schools but aren’t into a knowledge economy overnight.

We have a total of 182,600 primary schools serving 29 million children aged 5-9 – one primary school for every 158 children. We have 46,800 middle schools serving 28 million children aged 10-14 – one middle school for every 599 children. We have 42,448 secondary and higher secondary schools serving 25 million children aged 15 to 19 – one high/ higher-secondary school for every 600 children. A little less than half of these schools are private but are serving slightly more than half of school-going children.

On the surface, these numbers seem reasonable. However, when you consider that many ‘typical’ primary and middle schools comprise one or two classrooms and are staffed with a similar number of teachers, and you start accounting for the differences between school densities in urban and rural settings, the distances children have to travel to reach the nearest school, they quickly start becoming less impressive. A total of 55 million children attend some kind of educational institution from primary school through university (including madrassas, non-formal basic education, and vocational institutes) but there are still nearly half as many, 26 million children, out-of-schools.

Our education system is a pyramid, split roughly 50-50 between public and private institutions, with a wide base that narrows much too quickly which is insufficient to serve all school-aged children. None of this touches on the issue of low-quality education many schools impart. These are not the ingredients that a competitive global destination known for its high-tech industry and knowledge economy workforce make.

We have spent more than 20 years investing resources and pinning hopes on massive gains from the last stage of the education pipeline. That should have been matched by balanced investments to improve schools, the stages that feed universities. That has not happened because the promise of massive and immediate gains from ‘fixing’ the last stage has been a triumph of short-term thinking over long-term sustainable gains.

In Pakistan, the university-age population is typically defined as those between 18 and 24 years old. The three million people enrolled in universities in Pakistan at any given time make up only about 10 to 12 percent of that age group. There is only so much you can improve by polishing the last stage of an education pipeline whose primary, middle, secondary, and higher-secondary stages are poorly built. And yet, that is the path decision-makers were sold and chose to adopt.

The result has been an environment in which we have had a few flashes in the pan at certain times in certain places – a few years when fortune produced small islands of concentrated tech talent that even managed interesting achievements but fizzled out a few years later. The supply of talent dried up, the business environment made a turn for the worse, or the talent migrated/dissipated but could not be adequately replaced. By the time the government wakes up, it can be 10 or 20 years too late and an opportunity that could have been has passed by long ago.

Case in point: Tech startups. Three decades after the internet came to Pakistan, the government has finally come to acknowledge that the nascent tech industry, more than any other heavily subsidized sector of the economy, has the potential to create good jobs and earn foreign exchange without the need for massive import spending linearly proportional to output like manufacturing-based industries. Unfortunately, since the domestic tech sector does not have people representing it in parliament to lobby for its interests, it continues to be squeezed and/or neglected. The critical mass required to achieve ignition under such unconducive conditions is massive.

This is the environment in which scattered talent operates in our country. What is the depth of ideas the most well-traveled, seasoned, experienced, operators near the highest levels of power have to contribute?

A few days ago, the issue of the educated lot leaving/wanting to leave the country came up again on Twitter / X. A former senior official, who has had their time in the sun, suggested it might be time to consider preventing educated people from leaving the country (!). Bottling up the little bit of global-level talent in the country is not going to produce opportunities for them, but that may be too hard to grasp for some. Positively changing conditions such that more talent opts to stay of its own volition and achieve critical mass in some area does not appear to be an option.

The writer (she/her) has a PhD in Education.

Courtesy The News