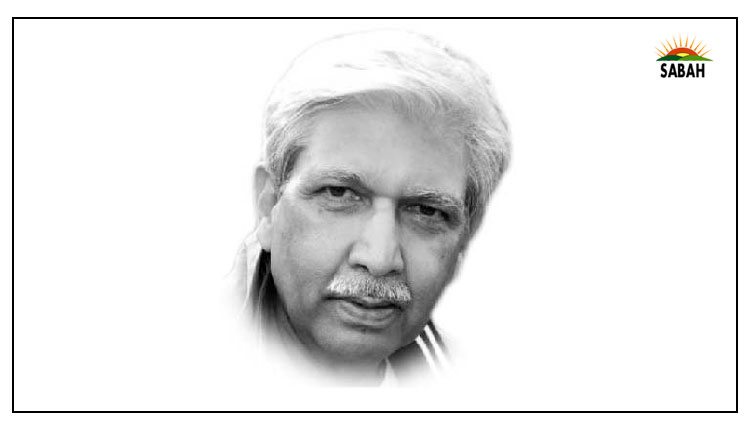

Why trading with the enemy is our best option… Shahzad Chaudhry

Travelling between Dubai and Abu Dhabi one cannot but be reminded of how Pakistani labour and professional support has raised the region from a bland desert into the metropolis it is today. My thought turns to the thousands (millions?) who left their homes in the early 1970s to turn Emirates into Gulf’s shining crown. Building techniques and processes since have changed and economies are far more skilled and automated replacing the indomitable spirit and doggedness of the Pakistanis with a greatly more sophisticated labour force. The graft is there for all to see even if the surgeons stand forgotten.

Pakistanis failed in upgrading their skills to the needs of newer and modern infrastructure and digital and integrated economies which now populate Gulf. Europeans, South-East Asians, Kerala Indians and a few Sri Lankans are a more common occurrence in UAE’s labour force. The Pakistanis have graduated to the taxi/Uber drivers on their own force but nothing more. Organised export of labour by these nations rests on prior certification and training for the tasks they are meant to fill in this region. That helps them raise precious foreign exchange while enabling prosperity to their people. Pakistan Air Force sent its best to help develop the UAE Air Force while the PIA raised Emirates Airline. Both now operate at the cutting edge and compete at the global level for expertise and professionalism while we struggle to find buyers of what is left of the PIA. More need not be said.

The problem is with our economic construct. We produce the labour our economy needs. And sadly, it is still at a very basic level. We compare ourselves in yields with the Indian farmer and find us lagging terribly in output. It comes from failing to learn and upgrade the techniques, the tools and the processes. The industry is lackadaisical and traditional. The seth has had it that way from his forefathers which has held him in good stead and the family together and is loath to try anything different for fear of risk and greater wealth which might attract disunion around greed. Entrepreneurs are few and far between and access to capital is almost non-existent – the government whisks away any capital in the market to keep itself going.

Our product range is basic and production capacity limited. We are a two-crop economy. Most industry is based around cotton and sugarcane. Production volumes are extremely low because the processes are antique and cumbersome. Inputs are unaffordable or unpredictable. Export potential is thus greatly restricted. On the other hand, global markets are far more sophisticated and modern for legacy products. There is no appetite for restructuring the economy around policy reform which seems impossible under prevailing political ineptness and pervasive crises. Our principal economic aim should be to export to earn precious dollars but nothing in the economy is optimised to that end. Our products remain attractive to only base level economies, if that.

To trade and export one must look at nations in geographic contiguity. Else the cost only multiplies, denying the opportunity to basic economies like ours to move up the ladder. The markets for the products must therefore correspond to the social strata which find them relevant and affordable. Afghanistan’s population is the same size as the province of KP. Most live on subsistence, and those that have the money are international citizens with abodes in Pakistan, Iran or Dubai. The country itself is in disarray. It also is the source of great malice in smuggling goods back into Pakistan where a market exists for consumer goods imported by Afghanistan for exactly this purpose. Basic Afghans needs in turn are already freely smuggled across the border. A sort of barter balance exists with little scope for anything extra.

Beyond Afghanistan lies Central Asia. A 72 million population in these five states is inviting except that many economies are already established around their own strengths and exportable surpluses in energy and commodities. The per capita income in these countries is higher than in Pakistan and socially they are better developed societies and economies in comparative terms around Soviet-era foundations. A conflict-prone Afghanistan in between makes connectivity difficult. Yet, effort must go on to seek both – stability and peace in Afghanistan and commodities and exportable products that can find markets in Central Asia. This could though be a long haul before an appreciable return accrues.

Iran is in a league of its own. Sanctioned and closely monitored any formal trade can turn a partner into a pariah. Till that resolves headway in formal trade with Iran is difficult. If barter and mutual currency swap can help regulate what goes on as illegal exchange of smuggled goods some order can help spur local economies. China and Pakistan despite an exemplary relationship only exchange goods worth twenty billion dollars annually. Of this Pakistan can only find market for around two billion USD annually. It reinforces the need for ‘relevance’ and production volume to benefit from the world’s most attractive and biggest market. It also is a crass example of mismatch between two economies and societies from a trade perspective.

That leaves India. It has a middle class which will grow to around 560 million by 2030 with cultural and societal similarities common to all who made up the subcontinent before it separated. Indian economy has moved many notches up. It is now the world’s top five in an increasingly corporate-ised construct mimicking modern economies. It holds the fourth largest foreign exchange reserves, indicating how much it exports what is needed by richer markets. As it moves leagues it leaves a space to fill for the 560 million middle and aspirational middle class who must still find supplies and sustenance relevant to them. That is where middling economies like Pakistan should be focusing to earn precious foreign exchange. Contiguity and neighbourhood add to that advantage. It reduces the cost of shipment and saves time by moving goods expeditiously. This should be an instant go-to solution for our overarching economic challenge.

Problem? India knows how desperately Pakistan needs trade to climb out of its predicament but is not ready to offer a helping hand to a mutually categorised arch enemy – history be hailed. Hence the repugnance which is now a default Indian recourse. India’s EAM let that be known in no uncertain terms on his recent sojourn here for the SCO. Instead, with each such mention Modi’s proclaimed 56 inches chest expands further by two more inches. Such is the tragedy of this benighted land. Can a man of some wisdom and some imaginative diplomacy bridge this yawning South Asian bias? For our own sake we need to revise our priorities and find pathways to surmount such infancy.

Courtesy ![]()