Seniority sacrificed: again …. Ali Tahir

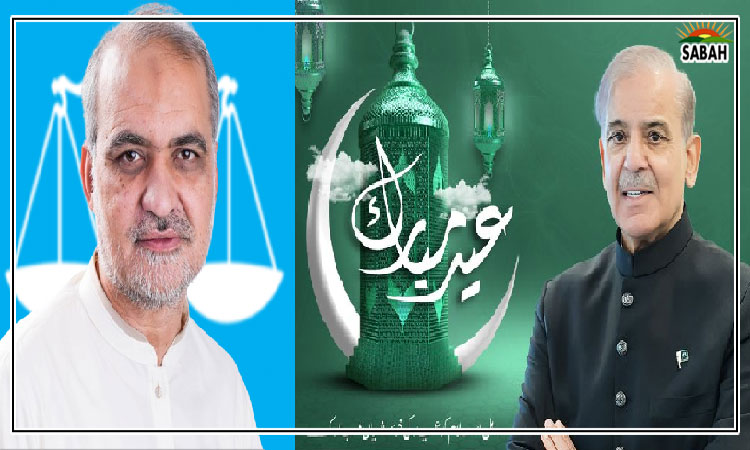

Now that Justice Yahya Afridi has been nominated as the next chief justice of Pakistan, and with the recent appointment of the third most senior judge as chief justice of the Lahore High Court, it becomes painfully clear that we, as Pakistanis, have gleaned little wisdom from our history.

Reflecting back to 1960, during Ayub Khan’s regime, a Constitution Commission was established under the leadership of former chief justice Shahabuddin. This commission examined the reasons behind the failure of parliamentary governance in Pakistan and to adopt a new constitution and as far back as 1960 suggested that seniority should be the primary factor in appointing the chief justice, unless compelling reasons dictated otherwise. Ignoring seniority could disrupt the court’s atmosphere. While Ayub Khan chose not to enshrine this principle in the constitution, it was nevertheless adhered to during his rule.

When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto ascended to power, this principle was breached. In 1972, Justice Sardar Iqbal was appointed chief justice of the Lahore High Court but chose not to ascend to the Supreme Court, preferring to maintain his position atop Punjab’s judicial hierarchy. Justice Maulvi Mushtaq, the next most senior judge, also resisted elevation in hopes of eventually taking over Justice Iqbal’s role as the chief justice of the Lahore High Court, creating an intense rivalry between the two men vying for the same position. Yet Bhutto had his own plans.

Overnight, the government enacted the Fifth Constitutional Amendment, which established fixed terms for the chief justices of both the Supreme Court and the high courts. Abdul Hafeez Pirzada, while introducing the amendment, justified it by pointing out that all other state positions – like the president, prime minister, and members of parliament – had fixed terms. Under this amendment, the chief justice of the Supreme Court would serve a term of five years, while a high court chief justice would hold office for four years. This move was evidently aimed at sidelining Justice Iqbal, who had fallen out of favour with the government. In a twist of fate, Justice Mushtaq, who had long awaited this moment, was overlooked, and Justice Aslam Riaz Husain, a junior to him, was appointed instead.

Subsequently, Bhutto pushed through the Sixth Amendment during the last session of the National Assembly, extending the terms established in the Fifth Amendment beyond the retirement age. This was widely believed to be a manoeuvre to retain Chief Justice Yakub Ali in his position, as he was nearing superannuation.

Fast forward to July 1977, when Ziaul Haq imposed martial law, fully aware of Justice Mushtaq’s grievances and dislike for Bhutto. Zia issued a presidential order that retrospectively revoked the fifth and sixth amendments, effectively ousting both the chief justice of Pakistan and the chief justice of the Lahore High Court, replacing them with his own choices. Justice Mushtaq then took the helm of the Lahore High Court, presiding over Bhutto’s trial – a trial recently deemed unfair by our Supreme Court answering a presidential reference – which ultimately led to Bhutto’s death sentence.

When Bhutto appealed, he raised serious allegations of bias against Justice Mushtaq, accusing him of meeting with Bhutto in Punjab House to request the chief justice position, a request that had been ignored.

As the decades rolled on, Benazir Bhutto, upon becoming prime minister, promised judicial reforms. Justice Nasim Hasan Shah was the sitting chief justice at the time but retired soon after her ascension. The next in line according to seniority was Justice Saad Saood Jan, yet he was bypassed in favour of Justice Sajjad Ali Shah, marking the infamous departure from the long-held tradition of appointing the senior-most judge.

However, Justice Shah soon found himself at odds with the PPP government on multiple fronts, particularly regarding judicial appointments. This discord led to the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of the government’s appointment of twenty judges to the Lahore High Court, declaring such appointments illegal. This case established a crucial principle: that the senior-most judge has a legitimate expectation to be considered for the position of chief justice, barring strong counter-reasons documented by the president or executive.

Yet, Benazir was displeased. How could a chief justice, appointed despite being junior, now uphold the seniority principle? Thus, she stalled the implementation of this principle in the high courts, leading to the opposition, spearheaded by Nawaz Sharif, siding with the Supreme Court. Eventually, when the president dissolved her government, Justice Shah sided with him, highlighting the volatile intersection of politics and judiciary, and why when politicians favour one judge over another, they are almost always at the receiving end.

When Nawaz Sharif took office, he too faced conflict with Justice Shah. The tension peaked in 1997 when Justice Shah recommended five judges for elevation to the Supreme Court. The government sought to block these appointments and reduced the number of Supreme Court judges from 17 to 12.

Justice Shah suspended this reduction, leading to a standoff, which ultimately resulted in the government reversing its decision to appoint the judges, but only after Justice Shah suspended the 14th Amendment to the constitution, which introduced Article 63-A to the constitution and which Nawaz felt would affect his majority in the National Assembly.

Simultaneously, petitions were filed in Quetta and Peshawar registries of the Supreme Court challenging Justice Shah’s appointment on grounds of seniority. A chaotic legal battle ensued, with the saddest sight in Pakistan’s judicial history: rival benches in the Supreme Court, a ten-member bench headed by Justice Saeed uz Zaman Siddiqui and a five-member bench headed by Justice Shah sitting in the same building and purporting to be the true Supreme Court. The matter finally culminated with the judgment in the Asad Ali case, which reaffirmed the seniority principle by declaring Justice Shah’s appointment unconstitutional, paving the way for Justice Ajmal Mian to become chief justice of Pakistan on the basis of seniority.

In 2000, Musharraf appointed Justice Falak Sher as chief justice of the Lahore High Court. However, his refusal to comply with the military’s directives regarding the district returning officers led to his removal and subsequent appointment to the Supreme Court. Once again, Musharraf appointed the junior Justice Iftikhar Hussain Chaudhry as chief justice of the Lahore High Court, an appointment that would echo through history, as the judiciary then appeased the military regime in Punjab, owing to the huge favour.

After Shehbaz Sharif’s government was dismissed in February 2009, he revealed that during a meeting with president Zardari, an offer was made to maintain the Sharifs’ governance in Punjab in exchange for extending Justice Abdul Hameed Dogar’s tenure via constitutional amendment.

In early 2010, a significant judicial crisis unfolded when Khawaja Muhammad Sharif, then Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court, was appointed to the Supreme Court. Simultaneously, Mian Saqib Nisar, the senior-most judge of the Lahore High Court, was named chief justice. Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry objected to these appointments, leading to the Supreme Court suspending their notifications. Resolution only came when the government yielded to the chief justice’s wishes, revealing how even the chief justice could violate the seniority principle. This situation necessitated the 18th Amendment to formally codify the seniority principle for the Supreme Court chief justice, which was met with widespread approval, only to now be repealed and a chief justice now to be selected from among the top three senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

Looking back at our history, it becomes evident that repeated political interference in judicial tenures and the disregard for the seniority principle have inflicted significant damage on both our democracy and our judicial institutions. Yet, here we stand today, seemingly undeterred by the lessons of our past, as we prepare to write another chapter that may echo the mistakes of those who came before us.

The writer is a barrister.

Courtesy The News