Rule by consultants …. Khurram Husain

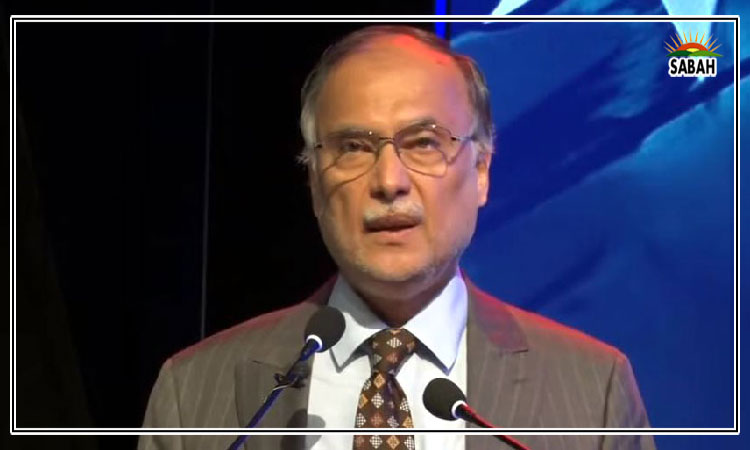

IT is odd that the government has recruited former State Bank governor Reza Baqir as a consultant to work on building its Sovereign Wealth Fund. Baqir has little experience building organisations. Besides, his tenure at the State Bank has left a legion of unanswered questions.

Baqir entered the State Bank amid high inflation and an abrupt change of guard at the finance ministry, when Asad Umar was ousted unceremoniously to be replaced with Hafeez Shaikh. Pakistan signed an IMF programme within a fortnight of Shaikh’s arrival, something Umar had struggled with for almost seven months.

Interest rates were already high in those days since Pakistan was still recovering from severe balance-of-payments stress as well as a period of high inflation fuelled by record-high printing of money. Direct government borrowing as a proportion of total broad money supply crossed 50 per cent in May 2019, having spiralled from early 2017.

The State Bank had already hiked interest rates all through the preceding year, but from May raised them by 250 basis points to 13.25pc where they stayed till Covid-19 hit. Baqir took a hit from all directions for this aggressive monetary policy. He had a hostile reception from the business community, and rumours swirled that at one event some attendees tried to physically accost him. His attempts to explain the high interest rates were not working, but he himself remained steadfast about the need for a tight monetary policy in order to combat inflation.

It worked. Inflation came down, and by early 2020, the economy was beginning to stabilise, in a situation very similar to the one we are in now, with inflation coming off its peaks, the primary deficit closing, reserves stabilising, the current account deficit narrowing but growth still remaining moribund. Is Pakistan ready for growth? I asked Hafeez Shaikh during those days. His answer was no, not yet.

But then, Covid-19 hit and everything changed. Immediately, the IMF programme was suspended, a $1.4 billion emergency funding line was thrown to Pakistan by the Fund, with more dollars from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, a debt service suspension initiative was availed by the country and interest rates were slashed to 7pc in a historic series of rate cuts. A string of subsidised credit schemes were announced by the State Bank that were premised on printing money. The idea was to support the economy during the period of lockdowns. However, in Pakistan, the government of the day took the money from the international community but lifted the lockdowns after barely a fortnight.

What ensued was one of the sharpest growth rebounds in the country’s history, taking everyone by surprise. Flush with liquidity, both domestic as well as foreign, coupled with large idle capacity, economic growth registered the strongest revival ever in Pakistan’s history, going from nearly zero to 7pc in one year.

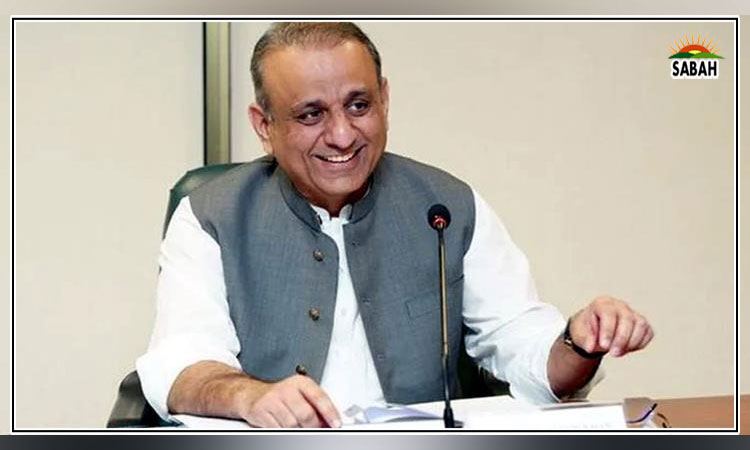

The elation in the government was also historic. Rarely have I seen ministers from government and supporters of a political party celebrate the return of growth with such exuberant fanfare. But there was a problem: it was all temporary. Months into the revival of growth, Shaikh began talking once more to the Fund for the revival of the programme, and by March of 2021, around the same time as the growth figures were coming in for the post-Covid year, the first programme revival was negotiated. The whole stimulus-lead growth euphoria was set to end, almost as soon as it began.

But Khan fired Shaikh within days of the programme revival and replaced him with Shaukat Tarin. And thence began the problem. Nobody was in the mood to unwind the stimulus and return to the Fund programme now that the Covid threat had passed, and Baqir obliged. Nobody wanted interest rates hiked or the exchange rate devalued. In May of 2021, the first signs of instability landed on Pakistan’s shores as the exchange rate began gyrating and inflation began registering hikes once more.

This was the moment for Baqir to urge the government to return to a saner monetary policy coupled with sound fiscal bases. Instead, through those months, even as Tarin announced an outlandishly extravagant budget, the State Bank kept interests low, even as the system began gyrating with price instability with each passing month. By November 2021, the State Bank moved into emergency mode as inflation turned into a raging fire, but it was too late. By 2022, when he left, Pakistan was on its way to being engulfed by a ferocious inflationary fire.

While he blamed this on global factors, indicators showed Pakistan’s inflation was far more aggravated than its peers, in the region or its own credit rating or any other category. South Asia had average inflation of 7pc in 2023, where Pakistan saw more than 25pc. All this was on the former SBP governor’s watch, whose central bank touted its monetary stimulus being equal to 5pc of GDP as one of its signature successes. The resultant inflationary fire was ours to handle.

Baqir had begun his tenure amid high inflation, caused by large-scale money printing, requiring high interest rates. He left behind an inflationary inferno fuelled by money printing the scale of which has few precedents in our history, necessitating interest rate peaks that were also the highest we’ve seen. Today, he is back to advise the government on how to build a Sovereign Wealth Fund. My only wish is that history should not be made again.

Courtesy DAWN