Uncertain times ….. Ehsan Malik

INVESTORS in Pakistan are well aware of, but often ignore, the challenges posed by the country’s volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA).

The country needs investment for jobs, tax revenue, exports, and reduced reliance on imports, especially food. New and existing investors should factor VUCA more into their expectations.

Businesses criticise governments for a disproportionate burden of taxes that penalise scale and investment, such as super tax. They fail to understand that the IMF does not buy into the government’s hopes of broadening the tax base. Therefore, its short-term programme is front-loaded with targets that can be met by taxing the taxed.

The country suffers from unreliable, environmentally unsustainable, import-dependent, and costly energy. The IMF is aware that fuel indigenisation, transmission, and distribution reforms could address Pakistan’s issues, but as these would take three-plus years to complete, its tariff prescription meets its short-term aim of controlling the fiscal deficit. Hence, a significant reduction in energy tariffs is unlikely, and manufacturing will remain uncompetitive.

It is crucial to review investment choices.

There are also no quick solutions to other major growth blockers — low productivity due to under-developed human capital and poorly negotiated trade agreements, with friendly GCC and the UAE knocking on the door for preferential access to our market. The country’s regulatory environment, too, results in high costs and slow decision-making, but the colonial-era bureaucracy is too well-entrenched to dislodge.

Given the current situation and the objective of an IMF programme, focused primarily on avoiding default, it is crucial to review investment choices afresh.

The FMCG sector in Pakistan has been an attractive opportunity for foreign investors. However, as this sector, which is a significant part of FDI, has a negative impact on the external account, it is important to consider the longer-term impact on the external account when evaluating FDI.

In the past two decades, many local groups have invested in projects carrying a sovereign guarantee or some protection, subsidy, or other state patronage. The recent spotlight on IPPs and the potential challenge to their contract terms does not augur well for further private sector investment, especially in power transmission and distribution, which Pakistan urgently needs.

There’s also growing realisation that import substitution through long-term protection to sectors in which Pakistan has no comparative advantage, is likely to build an externally competitive position, which undermines consumer value. Herein lies the dilemma. With high energy costs, low productivity, infrastructural constraints, and regulatory and fiscal burdens, even locally produced basic goods that benefit from favourable tariffs on ingredients versus finished goods would struggle to compete with imported goods if this protection were withdrawn.

Dispelling a common myth, it must be noted that redirecting investment from protected industries to export-oriented ones is not straightforward. Without a comprehensive industrial policy identifying Pakistan’s comparative advantage, piecemeal tariff changes are unlikely to yield positive results, except where such protection raises the cost of inputs to the SMEs in the export sector.

It would be better to wean manufacturing off protection through limited time and performance-based conditions, of which export competitiveness should be one. Also, the policy should factor in the reducing importance of cheap but low-productivity labour and the high cost of energy.

The takeaway for the private sector is that relying on guarantees and subsidies from a sovereign struggling to remain solvent is not sound strategy. Over the years, banks and industry have become risk-averse and inward-focused, reliant on state crutches and patronage often disguised as a national need, such as funding the fiscal deficit. In so doing, they have a misplaced hope of immunity from the state’s unpredictable policy framework.

Pakistan’s comparative advantage lies in its land and water, if optimally used to address food security, reduce reliance on imports, and generate export surplus. Fortunately, some large local groups are now turning to agriculture. Another hope is to deploy human capital for more productive use in the export of services, as manufacturing will remain beset with high energy costs. MNCs and local companies are training talent for software development, call centres, and back offices. Mining is another medium-term potential attracting investment. Finally, tourism’s unrealised promise is contingent on security conditions. Despite the VUCA times, there is hope, but it is not dependent on guaranteed terms or protection.

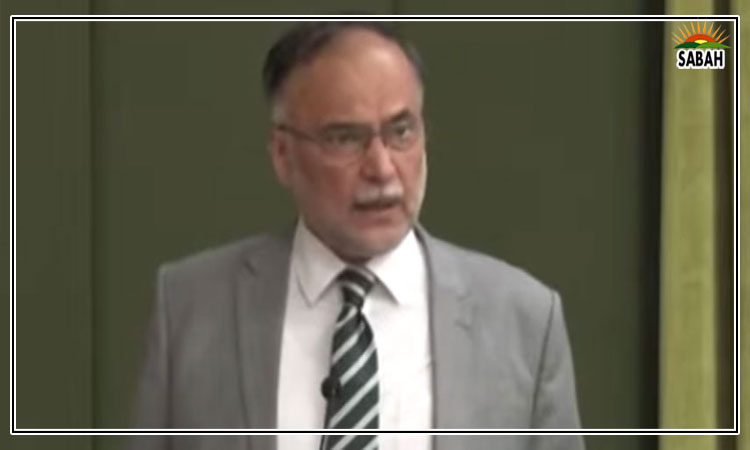

The writer is CEO of the Pakistan Business Council, a business advocacy body.

Courtesy Dawn, August 29th, 2024