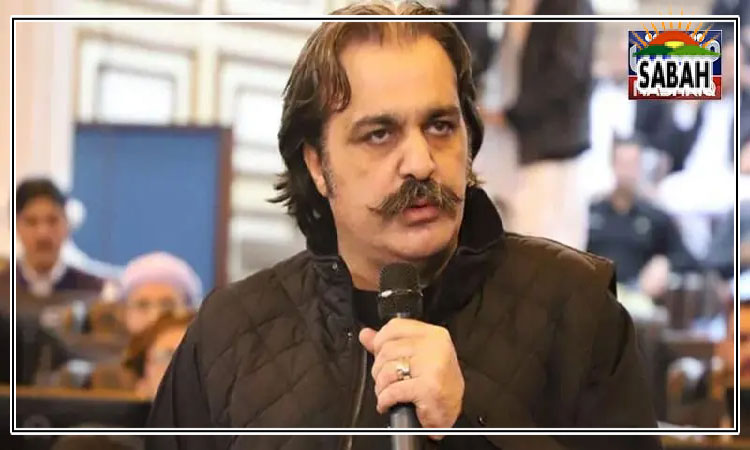

People power…Shahzad Chaudhry

There are numerous lessons to learn from the Bangladesh experience. A common history may not necessarily mean that the two people who were one have had similar social and political experience even if the ruling structures have mimicked one another over time. A nominal democracy has been spattered with long durations of extra-constitutional regimes and sponsored orders famously called the ‘Bangladesh Model’ – a regime heavily supported by the military in the background. We call it hybrid in recently coined taxonomy in Pakistan.

Bangladeshis like the Pashtuns and the Baloch in Pakistan have always been a politically and civilisationally conscious people with a history of struggle for their rights. Pashtuns of KP have rarely returned the same government twice to power except the PTI which in and of itself is a statement of note. The Baloch are a fiercely independent people bordering on being rebellious under any order. Bengalis on either side of the Indo-Bangla divide are educated, suave and nuanced in their politics and will not be subjugated for too long. West Pakistan learned that in 1971. Hasina Wajid and Co, which includes the Khaleda Zias and the usual power wielders in the vein of Pakistan – this is one heritage that has found common ownership in both nations – have tended to form a ruling elite assuming it has an abiding construct. It does not.

People have a threshold and upturn any order – Hasina Wajid found that out after assuming she had practically eliminated all opposition. How low is the threshold is the case in point. Economic development aside, exploitative regimes are extractive and manipulative to the point of exclusion in social economies as was the case in the recent rise of Bangladesh as an economic model. China is far too often fallaciously quoted as an example and mimicked for a single-party rule without first reading the context and the construct of the society. Nations can boast high GDP growth and FE reserves and can extrapolate average per capita in any number but it cannot hide the inequity that most galloping economies in capitalist markets are laden with. The rich get richer by multiple counts while those enabling growth in sweat shops remain poorly paid and excessively used.

Population growth rates in Bangladesh dropped considerably on the back of an educated workforce especially women yet the return in jobs and their quality remained restricted. With education must come ‘equal’ opportunity. It quite obviously was not the case. Quotas robbed people of merit and their right to compatible jobs. Cronies of the government and the patronised powerful were the ones to gain maximum favour. People reacted and then rebelled. On reaction the government, as is typical in developing and autocratic nations, used force to repress agitation. Only this time it backfired. The widespread defiance and confrontation among the people against the government turned into a popular rebellion which upstaged the entire order. This is how Egypt, the Philippines, Turkey et al saw their respective peoples’ movements and the ensuing changes in ruling structures.

Any order which disregards the will, and the wish of the people is riding roughshod and liable to pay for its omissions. People will have a good sense of how they are being marginalised or dispossessed, or disfranchised, but also recognise the collective sense of the state and its institutions in affording them the space and the chance to rectify what irks. When governments fail to remedy or exacerbate the perceived wrong is when collective conscience breaches the threshold. A trigger is all that is needed to light the fire. In the Bangladesh uprising constitutional institutions like the Parliament and the Supreme Court failed to intervene timely and rectify the perceived wrongs in allocating quotas in government jobs to preferred quarters by those who assumed unchecked power.

When the SC of Bangladesh finally acted it was already too late. The demands and the lament of the people had resonated widely, and the list of complaints only grown bigger. The state in disrespect of the other half of the nation-state construct – the people – then is faced with the consequences of the unrest. It initially tried suppression which turned into oppression over time intensifying people’s responses. If a state assumes impunity, it must face the wrath of its people. That is about the limit of a state’s power. The military, usually the state’s long arm, must carry people’s support to establish its credibility and hence deterrence in the eyes of the people. However, the moment the people stood against all odds including state’s power the military had only one way to go – align with the people to retain its credibility and deterrence both inside and outside Bangladesh. These are important lessons to learn.

Turkey’s example of an attempted coup some years back foiled by the people is a flip argument of how people can be the saviours and an element of strength for an order they support. Erdogan, the Turkish President, had established his political legacy around remarkable economic turnaround. He chose to arrogate to himself complete power by manipulating the judiciary and the media, causing undercurrents of disquiet. People’s possible reaction to such arrogance was foolishly preempted with a botched attempt by some within the military to take over. This was promptly put down by the remaining elements within the military and importantly the police forces. That is when the people came out in support of Erdogan and blunted any attempt to dislodge him. Serious consequences followed but Erdogan too was checked in his blatant attempt to arrogate all power to himself. Still an autocrat, he is a muted autocrat. Without such a remarkable economic turnaround and shared prosperity in the lives of the people he may not have found popular support. It helps to establish your credibility around indisputable performance.

Hasina Wajid could have learnt a thing or two from the Turkish experience. Given the peculiar history of the subcontinent of which Bangladesh was once a part people have been usually considered inured to high-handedness of power elites. Yet Bengal as a region is where most reaction to oppression took root. The struggles may not have always found success, but the unease was never lost to those in control and, in some cases, put down with force by the British. When people feel a system is exploitative and the return due to them is unfair, they will inevitably react. Such sentiment cannot be held back for too long. The trick is to judge the moment when turmoil needs to be checked lest it turns into chaos. Hasina Wajid failed to judge that moment. Constitutional institutions failed to timely intervene which led to missteps and ultimately forced the inevitable meltdown. One of the many ways nations fail.

Courtesy The Express Tribune