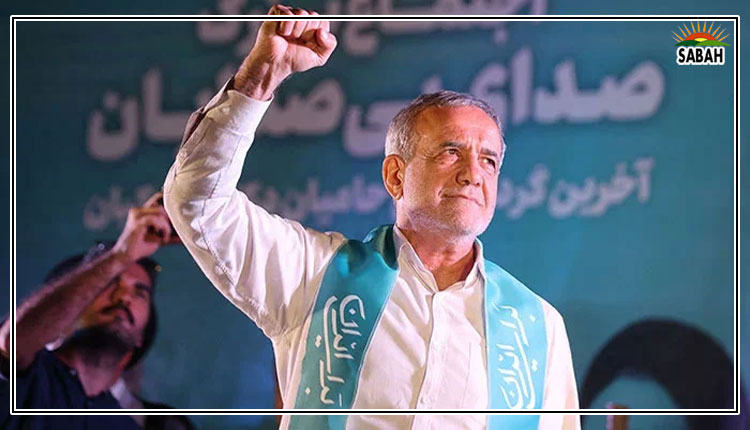

The ‘change’ in Iran…Hussain H Zaidi

There is a sense of deja vu when one looks at the victory of reformist Masoud Pezeshkian in the recent presidential election in Iran. In 2013, another reformist, Hassan Rouhani, was elected for his first presidential term by landside amid promises for much-needed economic recovery and the opening of the socio-political order. This is what calls for reforms in Iran essentially entail.

Rouhani went on to win the second term four years later. But the high expectations that he carried on his shoulders remained largely unfulfilled due to a combination of internal and external factors.

I was present in Tehran when Rouhani was elected for the first term. As the clergy-controlled Iranian establishment looks down upon rallies and processions except when they are staged in its support it was a pleasant surprise for me to see people come out in droves, celebrating the triumph of their favourite candidate.

A greater and more pleasant surprise was the spectacle of women throwing off their scarves, which is obligatory for them to wear as part of the regimes Islamic measures. Never before or later did I see women in public places with bare heads. By all accounts, that gesture signalled their expectations that Rohanis election would pave the way for their emancipation. But that was not to be.

In fact, if we take a longer view of the Iranian presidential elections, well see a pattern of reformist and hardliners or pro-establishment candidates taking their turns in carrying the day. In 1997, reformist Mohammad Khatami sprang a surprise when he was elected president. He remained in office for two back-to-back terms until 2005.

Before his election, Khatami had proposed the idea of dialogue among civilizations, which many believed was an indication that he was prepared to do business with the West, particularly, the Great Satan, as the US was branded by Irans top leadership. Freedom of expression, a more inclusive democracy, and market-oriented economic reforms also figured prominently in his electoral campaign.

As part of engagement with the West, Khatami visited several European capitals. A symbolic highlight of his first term was the football match played between Iran and the US in the 1998 FIFA World Cup. Called the mother of all games, it marked a unique sporting event in which the two adversary countries, which used to be strategic allies before the Islamic revolution, faced off.

However, Khatamis efforts to open up Iranian society and economy or bring about reproachment with the West drew a blank, mainly because the Iranian establishment was not well disposed towards either. Any hope, if there was one, of a meaningful change in the regimes domestic or external policies was extinguished when the 2005 presidential polls saw the victory of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a hardliner. He was re-elected in 2009 amid widespread protests by the reformists, who questioned the fairness of the election.

The reformists struck back through the consecutive victories of Hassan Rouhani in 2013 and 2017. A singular achievement of the Rouhani government was the July 2015 joint comprehensive plan of action (JCPOA), commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal. The JCPOA represented a trade-off: Iran would put the curbs on its nuclear programme in exchange for lifting or softening of international sanctions that had crippled its economy.

The agreement signalled a shift in the Wests strategy from bullying to constructive engagement with Tehran and the willingness of the two sides to turn swords into ploughshares. However, in 2017, Washington under Donald Trump withdrew from the deal and restored sanctions on Tehran. As the bulk of international trade is conducted in American dollars, the renewed US curbs meant that most of the exporters and importers across the globe, including Pakistan, would hesitate to do business with Iranians, making their economic revival hard to come by.

In early 2018, protests broke out in Mashhad, Irans second largest city, which quickly spread to other parts of the country, over rising unemployment and prices. Not only that, but the protests also provided an opportunity to the exasperated people to launch a vitriolic attack on the political system. Irans foreign policy, which commits the government to divert a considerable portion of public resources to supporting friendly governments and movements in the region, also came under stinging criticism.

In a game of musical chairs, the reformist Rouhani was succeeded by a hardliner, Ebrahim Raisi, whom he had defeated in 2017. A year after his inauguration, protests broke out in Iran over the death of a young woman named Masha Amini, who was detained by the police for allegedly not wearing the mandatory hijab. Her death, which many set down to the beating by the police, prompted a large number of women to publicly put down their hijab or cut their hair in protest, as well as led to a widespread demand for an end to the regulations, including hijab, discriminatory against women.

But the protests and demands didnt much impress the government. Raisis tenure was cut short when he died in an air crash last May.

Why have the reformists in Iran, despite being in the office of the president intermittently for full terms, not been able to hit the mark? To answer this question, we need to look at Irans political system. There are two power poles in Iran: One comprises the popularly elected president and the majlis (legislature); the other is represented by the clergy-dominated establishment presided by the supreme leader or Rahbar. The one stands for popular will; the other believes in controlled democracy.

The Rahbar holds a unique position in the Iranian political system. He is the guardian of the revolution, the custodian of the constitution, and the overall supervisor of the system. In all vital public matters, his is the last word.

Post-revolution Iran has witnessed a relentless struggle of reformists against hardliners, particularly as a new generation sprang up, for more openness and democracy. However, hardliners because of their greater power and influence and commanding the loyalty of the military, particularly the revolutionary guards, have remained a tough customer.

Meanwhile, the Iranian economy continues to bleed. Having registered robust growth of 8.8 per cent in 2016 in the wake of the lifting of international sanctions, the economy grew by only 2.8 per cent in 2017 before contracting by 1.8 per cent in 2018 and by 3.1 per cent in 2019, as the renewed curbs stung it. In 2022, it registered a modest growth of 3.8 per cent, which went up to 4.7 per cent in 2023. In 2024, economic growth is projected to fall to 3.4 per cent. Low growth has been accompanied by high inflation: 34.7 per cent in 2019, 36.4 per cent in 2020, 40.2.7 per cent in 2021, 45.8 per cent in 2022, and 41.5 per cent in 2023. The IMF projects 37.5 per cent inflation in Iran for 2024. Because of the sanctions, Iranians perpetually face shortages of essential commodities, which spike their prices, as well as of industrial raw materials, which puts the brakes on economic growth. The sanctions particularly hit hard Irans petroleum sector, the lynchpin of the countrys economy and exports. As a result, the country faces a shortage of foreign exchange, which pushes the domestic currency down steeply.

Iran has immense geo-strategic significance, especially at a time when the region is in turmoil. It has some of the worlds largest gas and oil reserves. Apart from improving relations with the West and other countries in the Middle East, the country needs to overcome internal contradictions and conflicts to realize its enormous economic potential.

After winning the election, Pezeshkian promised that his victory would usher in a new chapter in the countrys history. We are ahead of a big trial, a trial of hardships and challenges, simply to provide a prosperous life to our people, he said.

Can Pezeshkian lead a successful compromise both within the country between the forces of change and the establishment and between Iran and the West and as its Middle East neighbours?

Courtesy The News