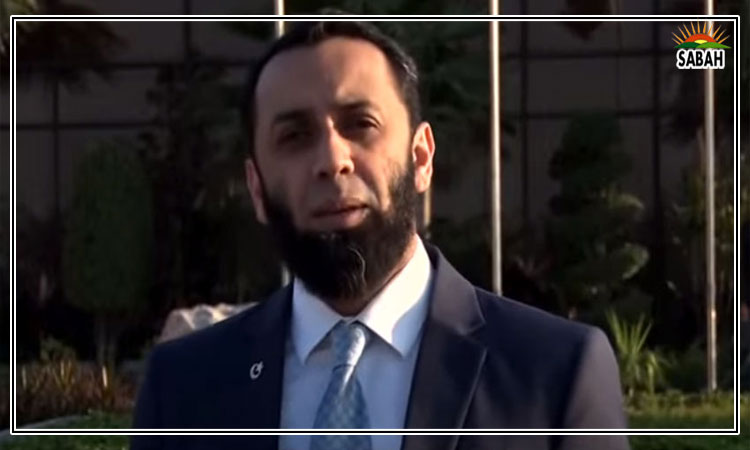

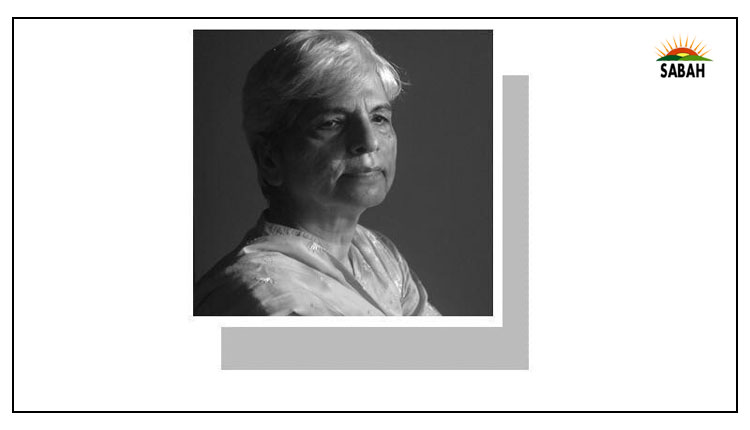

Why insecure?…Zubeida Mustafa

IN his memoirs, Foundations and Form, Mukhtar Husain writes about his first school experience: In 1955, I started attending Mrs Corks Private School which was run by a British lady, Mrs Corks. The Corkses lived in a stone house with terracotta roof tiles, located in its own enclave within our Colony and surrounded by a low wall. I was just five years old and hated going to school every morning. I would cry all the way and would go on crying in school as well. At times, I was so difficult that I was sent home during the mid-morning break. Shaukat Aziz [later on, the prime minister of Pakistan], who was perhaps a year older, was often asked to walk me home. But I settled down and soon I was doing well

I was curious to find out what upset Mukhtar at school. He told me that he had no idea. But I suspect it was the strangeness of the language used at school which did not allow him to express himself fully. Being an intelligent child, he must have been frustrated. He was accustomed to speaking Urdu at home and the school was all English. A child cries when he feels insecure. Being away from the comfort zone of his home that has his mothers reassuring presence can be quite distressing for a young child. Add to that the barrier of language that prevents the child from communicating with others, and the situation becomes quite distressing.

In any case, Mukhtar was fortunate to have an understanding teacher who sent him home when she felt that Mukhtar was inconsolable. He later adjusted, and to his credit learnt English, which is evident from the impeccable language of his memoirs.

Nearly 70 years on, education in Pakistan is in the doldrums. A major factor responsible for the mess is the bizarre and hybrid pedagogy that is employed in the low-fee private- and public-sector schools, with the exception of Sindh (however, there is little by way of education there). The language used by the teachers is commonly spoken by the population of the area where the school is located. The textbooks are in Urdu or English, which the students are expected to read, and then write their answers to the questions accordingly.

Our children grow up to be book-hating adults.

As a result, there is a lot of rote learning going on and hardly any original writing and critical thinking is taking place in our classrooms. We still have to decide which language is to be the medium of instruction and what is to be the role of the mother tongue in the education system.

Our educationists do not even know how a child learns a language and how it should be used in school to maximise the benefits of education. In a nutshell, the child learns a language the natural way, ie, by listening to it. This process begins soon after birth. Children pick up the language of their community by listening to their family members, and later on, in the marketplace playground, so to speak. They do not have to be taught grammar or syntax; these come naturally to them by listening to others. That is why everyone (if not handicapped) speaks a language even if he has not attended school. Literacy is another ball game and has to be taught in an organised setting.

By trying to introduce in our education system another language that is not familiar to the child, and through teachers who lack competency in the other language themselves, we confuse the language acquisition process.

The worst impact is on the childs ability to read and her interest in books. Researchers say that the more children read, the more they know. This, in turn, enhances their cognitive development. It is also said that if reading is made an unpleasant and laborious exercise from the start a child would just not enjoy reading books. The fact is that a person who is an avid reader also enjoys it.

Our education system is destroying our children by thrusting on them a language unfamiliar to them. This is done prematurely, without paving the ground for it. It is done in most cases by teachers who are not proficient in the language themselves. The method is also wrong. Instead of focusing on the vocabulary and starting with the spoken language, we want to teach them literacy skills that can be tedious. It is no wonder then that our children shun books. They grow up to be book-hating adults.

Children are thus denied the experience of self-discovery that comes from reading books. This is a tremendous loss; the self-directed learning instinct is never kindled in them. Critical thinking that is innate to human beings is destroyed.

That would explain why the book industry in Pakistan is not doing well at all. When children have not been exposed to books in the language they can understand and enjoy, they grow up with no interest in them.

Courtesy Dawn