Where is our playground? …. Ali Khayam

CHILDREN in Pakistan have the least amount of playtime in schools as compared to the neighbouring countries in South Asia. According to a report published by UNDP in 2018, only seven per cent of Pakistani children and youth have access to a playground in their school or community, and over 60pc of them reported not having frequent access to sport and play activities. These numbers are worse if we consider gender-segregated data.

Having access to sport and play is a right of children and young people, and not a luxury. Play is essential for the cognitive and holistic development of children during their formative years. Numerous studies and research have established the link between regular and quality playtime for children and their positive physical and brain development. Participation in sports is also tied to better academic performance, enhanced cognitive skills, and improved educational outcomes among the young. Engagement in team sports, in particular, fosters teamwork, discipline, and leadership skills, which are transferable to academic and professional settings.

The results of a randomised control trial published by the Aga Khan University indicated a significant reduction in bullying and peer violence, and symptoms of anxiety and depression among adolescents when a regular sport and play programme was offered in 20 government schools in Hyderabad, Sindh.

April 6 is celebrated each year as the UN International Day of Sport for Development and Peace. It is imperative to take stock of our performance as a nation, and as a society, to see how well we have delivered on the goal of providing equitable access to sport and play to all young citizens of Pakistan. But as the figures presented here suggest, we have failed miserably, both as a state and society.

Schools should offer structured and meaningful physical education programmes from primary till the secondary level.

As a state, sport has never been a priority. Whenever the Olympics or Asian Games come around, we lament the ever-shrinking size of our delegation and the medal drought. ‘A nation of 250 million with no medals’ becomes a popular hashtag. But the hue and cry does not manage to convince the country’s policymakers to make the right choices. What are the right choices?

To begin with, policymakers must stop seeing sports and education in isolation. At the provincial level, the two ministries must be merged and the authorities come up with comprehensive sports and education policies. Schools should offer structured and meaningful physical education programmes from primary till the secondary level. At present, there is no provision of PE teachers at the primary school level in any of the provinces or federal territories of Pakistan. This is, in fact, the most critical age group where children need quality play and PE programmes to develop essential motor skills. The right decision in this regard would be to appoint PE teachers in all public primary schools and invest in their training.

Some secondary schools have appointed PE teachers, but in most cases, these teachers are mere disciplinarians, instead of engaging children in purposeful sports activities. All the provincial education ministries must make it a priority to improve the quality of PE curriculum and equip teachers with modern-day PE tools and standards.

There is an acute shortage of playgrounds in educational institutes. Public and private schools alike do not prioritise allotting a play area within the school premises. Many public schools may have the space, but lack of funds, which deprives children of an opportunity to play sports at a decent facility. The crisis of play spaces is worse at privately owned schools, that cater to a large part of the total school-going population of Pakistan. Barring a few elite schools, most private schools are established in buildings or houses which aren’t suitable for offering children a wholesome experience. Most of these schools do not have space for play areas.

It is high time that all provincial governments increased budgetary allocations to ensure the construction of safe and inclusive play areas in public schools. And private schools must also be regulated more effectively to ensure that they are only allowed to operate and charge a substantial fee if they provide a sufficient standard of education and sports to children.

Beyond schools, city and local governments must also get their priorities right by ensuring that areas assigned for playgrounds and public parks in original city plans are maintained according to global standards, and the construction of commercial projects, such as business centres and marriage halls, are not allowed on these spaces.

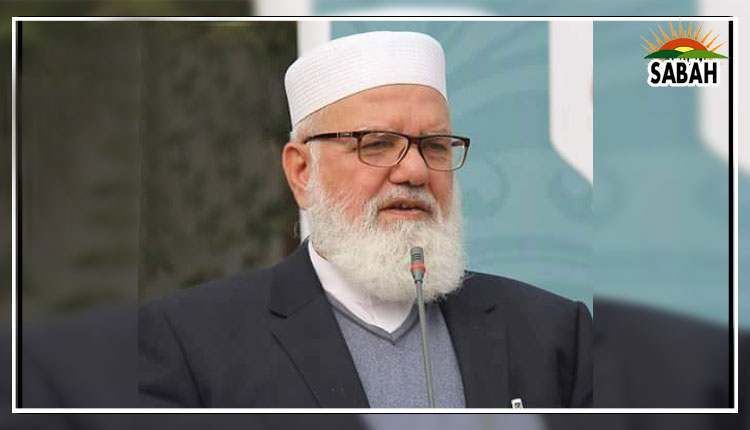

As a society, we have failed to provide girls with equal access to sports. Certain cultural norms are enforced to restrict the participation of girls in sports. Last year, the media reported at least three different incidents where religious leaders called for a ban on girls’ participation in sporting events in Swat, Charsadda and Gilgit-Baltistan.

Girls have to face multiple challenges if they want to exercise their right to play. Social taboos, such as darker, sunburnt complexions, and myths around menstruation, perpetuate several layers of fear and inhibition, which force many young girls to drop their dream of playing a sport. Those who manage to overcome these socially constructed barriers and take the leap of faith and go out and play, have to face the challenges of safe commute and accessing public playgrounds which are scarce; the ones which are available are mostly occupied by men.

While policymakers must ensure equal access to sport opportunities for girls by removing barriers and ensuring culturally appropriate and safe outlets of play, it is also the duty of civil society, religious leaders and academia to play their due role in improving female participation in sports.

The writer works as the country director of the non-profit Right To Play International in Pakistan.

akhayam@righttoplay.com

Courtesy Dawn, April 6th, 2024