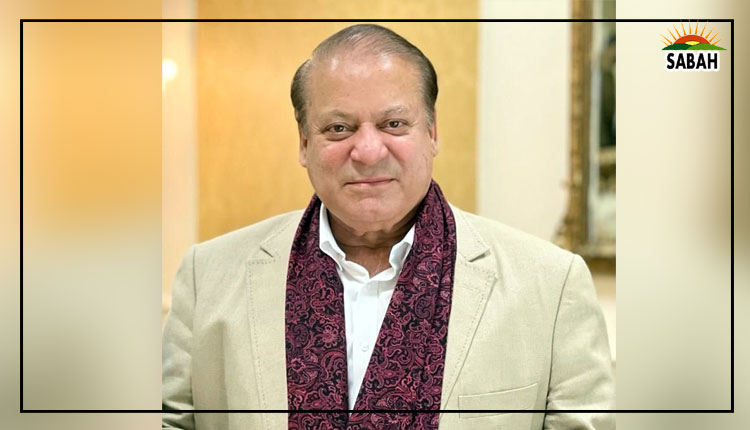

Candidates for Election 2024…Ahmed Bilal Mehboob

NOW that the final list of contesting candidates has been released by the Election Commission of Pakistan, it has emerged that an unprecedented number of candidates (almost 18,000) are chasing 1,125 seats in the National Assembly (NA) and the four provincial assemblies in a contest which is less than two weeks away. A couple of cases may still be awaiting final adjudication in the apex court on the validity of candidature of those politicians whose nomination papers were rejected by the concerned Returning Officers and the decision upheld both by the appellate tribunals and the high courts. The Supreme Court has, in general, been more generous to the rejected candidates than the high courts and the appellate tribunals as it ruled that even a person absconding from the law has the right to be a candidate in the upcoming election.

Never before in the history of the past 11 general elections have we seen over 19 candidates on average vying for a single NA seat. The number of competitors has been steadily going up since the first general election in 1970 when about five candidates competed for each NA seat on average. Only the number of candidates in the 2013 general election comes close when around 17 candidates competed for each NA seat. In that respect, the elections have been getting more competitive with time as the average number of candidates per seat in the national legislature has grown by 280 per cent since 1970.

Fiercer competition is not the only distinctive feature of the coming election. We are seeing an extraordinarily high percentage of independent candidates in the run. The fact that PTI candidates, after losing a common election symbol, are running as independent candidates, only partially explains this high number. The PTI claims to have fielded 236 candidates for the NA, who are contesting under various election symbols. In the past 11 elections, the number of independent candidates for the NA hovered around 53pc whereas now 63pc of independent candidates are competing. The additional 10 percentage points translate into an additional 500 independent candidates, which means that there are 264 (after subtracting the PTIs claimed candidates) additional independent candidates. These may be covering candidates for the PTI or part of another scheme which may unfold after the election.

This trend of a higher number of independent candidates is slightly stronger in the case of the provincial assemblies where 66pc of the candidates are independent. Unless the returned independent candidates, especially those nominated by the PTI, display a strong character and party loyalty, there is a likelihood that such independent legislators will be vulnerable to huge pressure and temptations. In the 2018 general election, returned independent candidates played a decisive role in the formation of the PTI-led governments at the federal level and in Punjab. The proverbial Jehangir Tareen private plane had frantically ferried such legislators to Islamabad and Lahore at the time. Since the stakes and likely number of independent legislators are much higher this time, one may see a record-breaking push and pull to win over independent legislators. What kind of effect such an exercise at such a large scale would have on the political landscape, especially on whatever little is left of ethics in politics, is not difficult to comprehend.

Fiercer competition is not the only distinctive feature of the coming election.

Women candidates nominated by the political parties on general seats this time barely constitute around 4.77pc when collectively assessed both for the NA and provincial assemblies. This is lower than the minimum 5pc threshold prescribed in the Elections Act, 2017, for each party to follow. The PTI list indicates a slightly higher, about 8pc, share of women candidates on general NA seats.

In previous elections, political parties had not been fair to the youth when picking candidates. In 2018, political parties gave tickets for the NA and four provincial assemblies to only 19pc candidates of 25 to 35 years of age whereas young registered voters from 18 to 35 constituted over 44pc of the total registered voters. It may be surprising to some that the TLP topped the list of parties who gave relatively more tickets to young candidates from 18 to 35 years who constituted over 36pc of its total candidates for the NA and provincial assemblies. Political parties such as the PTI which are generally associated with the youth were not very generous in awarding tickets to young candidates. The PTIs share of young candidates was a mere 17pc, while the PPP was not much better with only 18pc. The PML-N awarded the least percentage 13pc of tickets to young candidates. Sadly, party-wise statistics of young candidates are not available yet for the upcoming election but one hopes the parties would have realised the importance of youth and their voting potential and awarded more tickets to younger candidates this time.

While discussing candidates for Election 2024, it may not be out of place to indicate that despite reports of rejection of a much higher number of nomination papers during the scrutiny by Returning Officers, a far higher percentage of candidates have emerged as valid candidates out of the scrutiny and appeal process than in the past two elections. In the ongoing electoral process, 68pc of NA candidates who filed nomination papers ended up as valid candidates after clearing the ROs scrutiny and appeals in the appellate tribunals. The figure was 61pc in 2018 and 57pc in 2013, indicating that a larger number of candidates were dropped in scrutiny and appeals or withdrew from the contest.

The percentage of candidates for provincial assemblies who have cleared these hurdles is not much different either. Even the overall percentage of nomination papers rejected by ROs were not very different this time compared to the previous two elections. Overall, 13pc of nomination papers were rejected by ROs during the recent scrutiny compared to 10pc in 2018 and 15pc in 2013. It is possible that political parties such as the PTI may have suffered more from the scrutiny but that can only be verified after authoritative data becomes available.

Courtesy The Express Tribune