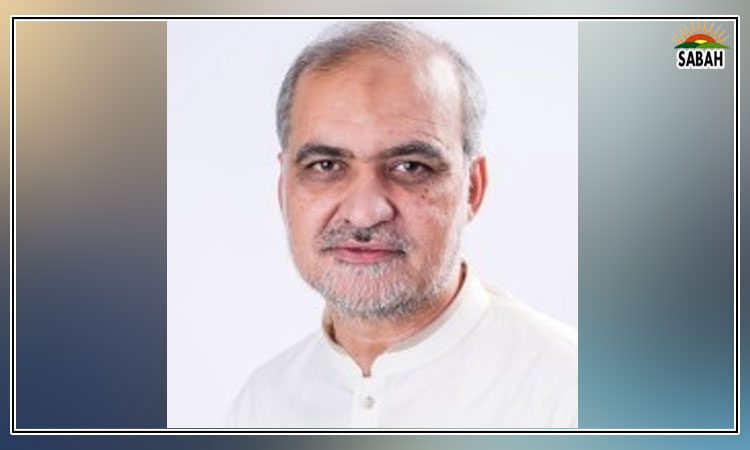

Balochistan in hot water…Ali Tauqeer Sheikh

BALOCHISTAN is fast emerging as Pakistans climate hotspot. In recent years, it has become a favourite destination for the monsoon rains. Owing to widespread flooding, all ground links of the province with the rest of the country were cut at least twice in the last two years. Imagine a landmass that is larger in size than at least seven states in the US, including Massachusetts, and is disconnected from the mainland for weeks and months because the rains had washed away poorly built road links and railway lines. This is more damage than any outside enemy could have inflicted on Pakistan. Clearly, climate change has graduated from a nontraditional security threat to become a perilous hazard to national integration.

The province has, in recent years, received more rains than many parts of Punjab, the traditional recipient of heavy monsoon downpour. Balochistan is now facing a dual water crisis: while struggling with extreme water scarcity, the province is overpowered by annual inundation. Both scarcity and excess are accelerated by climatic changes.

The character of agro-ecological zones has begun to change, affecting unique characteristics and environmental conditions of different areas within the province. Some 10 rivers and basins in Balochistan have completely exhausted their water resources. Per capita water availability, including groundwater, has reduced over the years at a much faster rate than the national average, forcing outward migration.

Governmental efforts to increase water availability through such measures as water management projects or rejuvenating aquifers and karez maintenance have lacked long-term commitment. Worse, successes have rarely been up-scaled from project level for wider application. The plans to address the water crisis through check-dams or construction under the 100-dams project do not fully address the sedimentation, dredging and desilting challenges that are resolved in similar geographies elsewhere in the world. These efforts are now also hampered by multiple climate threats, particularly rising temperatures, erratic rainfall patterns, and extreme events such as floods, droughts and heatwaves.

Both water scarcity and excess in the province are accelerated by climatic changes.

Excessive precipitation poses a triple jeopardy to the province: a) loss of topsoil because of heavy run-offs; b) large-scale damage to government infrastructure; and c) widespread loss of human lives, livelihoods, livestock and other assets, particularly houses and communal lands.

Lets see the ramifications of these trends and initiate a conversation on how to cope with climate change in the province.

Topsoil Loss: Balochistans arid and semi-arid lands and fragile ecosystems do not have the absorptive capacity for heavy rains. The province is particularly vulnerable to topsoil loss, which has long-term negative impacts on soil fertility, soil structure, productivity, biodiversity, and ecosystem services.

Run-offs and topsoil losses, however, can be measured at local and watershed levels by applying different models and methods. Such studies are necessary to plan conservation and mitigative measures. Ecologists and environmental economists can calculate the run-off and rate of soil loss, and also estimate their environmental and economic values. Estimating the economic impact of soil loss on the sediment in reservoirs is routinely undertaken by assessing the reduction in capacity for holding floodwaters and water reserves for power generation. Several government departments have the capacity to calculate these costs and help build a case for accessing the loss and damage fund whenever it is operationalised.

Infrastructural Loss: The provincial infrastructure is not designed to withstand heavy monsoon rains and floods. The rains have been record-breaking and have resulted in disproportionately higher economic losses, undoing the development gains of the past 75 years. According to the governments Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA), Balochistan lost $1,625 million in the 2022 floods, with damage to schools, hospitals, roads, bridges, power stations, and other public infrastructure.

Critics have blamed these heavy losses on poor and nontransparent procurement processes that do not adhere to existing construction standards and materials. It is, however, also important to see how far construction standards and guidelines have been climate-proofed to withstand the accelerating climatic changes. While a parliamentary committee or a judicial commission should investigate the first, the second would require technical studies and the revision of national construction standards and guidelines, a process that has to be led by the Pakistan Engineering Council together with the federal and provincial planning boards.

Human settlements: Hamlets are scattered all over the landscape in Balochistan, often times in harms way. The PDNA has not given any exact figure, but the National Disaster Management Authority estimated that almost 242,000 houses were destroyed or damaged in 24 districts during the 2022 floods. Additionally, the reports suggested that 304,000 acres of crops were lost and 500,000 livestock killed in the province. These are big losses for people living on subsistence and below the poverty line.

Cash disbursement through the Benazir Income Support Programme can only be a one-off activity. The province needs long-term approaches, particularly risk transfer and insurance mechanisms for human lives, shelter, standing crops, livestock and micro-businesses. A recent innovation has been made by the World Banks $500m Sindh Floods Emergency Housing Reconstruction Projectthat gives a cash grant of Rs300,000 to construct flood-proof houses. The project empowers recipients, especially women-led households, and ensures that each beneficiary receives land ownership documents from the government. This project presents a strong case for replication in Balochistan.

As the largest province with less than six per cent of Pakistans total population, Balochistan has been punished for decades for having a smaller population. The just-approved 2023 census will further reduce the financial award to the province by the federal government, at least compared to Punjab and Sindh. Enabling climate-resilient housing will help address the communal climate adaptation needs.

For decades, Pakistan subscribed to the Anglo-American view that the Russian southward expansion was inspired by the will of Peter the Great, who wanted an all-weather port in Balochistans warm waters. Balochistan has paid a heavy price for this view by enduring underdevelopment and nominal investments. We know now that this policy has also accentuated climate vulnerability and put Balochistan in the hot waters of climate change.

Courtesy Dawn